What I have called Civilization Disease is, I think, inextricably connected with humanity’s delusion of self and separation. Here’s what I think led to that:

- Nature is always trying out new possibilities and variations in the endless search for a better ‘fit’ for all creatures with each other and the evolving environments we all live in.

- When human brains got large enough, one possibility that nature tried was to create a conceptual representation of reality, with the human in the ‘centre’ of that representation. It’s a completely artificial construct, but it still had possibilities for evolutionary advantage. In fact, it’s conceivable that in a rudimentary way this false sense of self and separation is briefly evoked in many creatures during periods of extreme stress, when this illusion can trigger a fight/flight/freeze response, which is quickly “shaken off” as if it were a hallucination (you can see wild creatures do this) once the peril has passed.

- At various points over the past 2M years, humans have evidently faced extreme dislocation and the threat of extinction. We survived primarily by migrating to less naturally hospitable areas and adapting in place. One of those adaptations might well have been more extensive use of the represented model of self and separation.

- According to the entanglement hypothesis, there came a point in human civilization when the neural connections in the brain responsible for perceptual and conceptual activities became ‘entangled’. This allowed greater ‘sensemaking’ of what humans perceived, but also blurred the distinction between ‘what is’ and the brain’s conceptual representation of ‘what is’, to the point humans could be conditioned to act as if the latter was the ‘real’ reality.

- At that point, the primary function of the brain became to ‘make sense’ of everything it perceived by relating it to the seeming veracity of its conceptual representation of reality. And thus, everything had to be related to the ‘self’, the anchor of this model of reality.

- Compounding this immense and endless mental challenge, the integrated brain was now able to imagine things it had conjured up, and to represent them as real within the model. It could then imagine gods to be real, the past and future to be real, and things in that past and future to be real. With the development of abstract language, humans could then reassure each other of the veracity of their imagined models, and start to align them, further entrenching the illusion that this mentally constructed model was real. This imagined truth, which we call “knowledge”, supplanted instinct as the primary way in which humans understood themselves to be making decisions.

- The problem is that not only was this mentally constructed model not real, but it was not actually what was making decisions. Decisions continued to be made instinctively, based solely on biological and (more recently) cultural conditioning, as they had always been, so now the self had to rationalize all those decisions, to justify its existence and its ‘truth’ that it was real and in control of the human it presumed to inhabit. This gave rise to a host of new emotions (not felt by wild creatures or early humans) like hatred, shame, guilt, envy, jealousy, loneliness, sorrow, depression, and personal love, all of which depended on judgements, expectations, disappointments and other disconnects between what was actually real, and what the self imagined ‘had’ to be true to make sense of what was happening, and why that did not jibe with what the model of self said ‘should’ be happening — a colossal psychosomatic misunderstanding of reality.

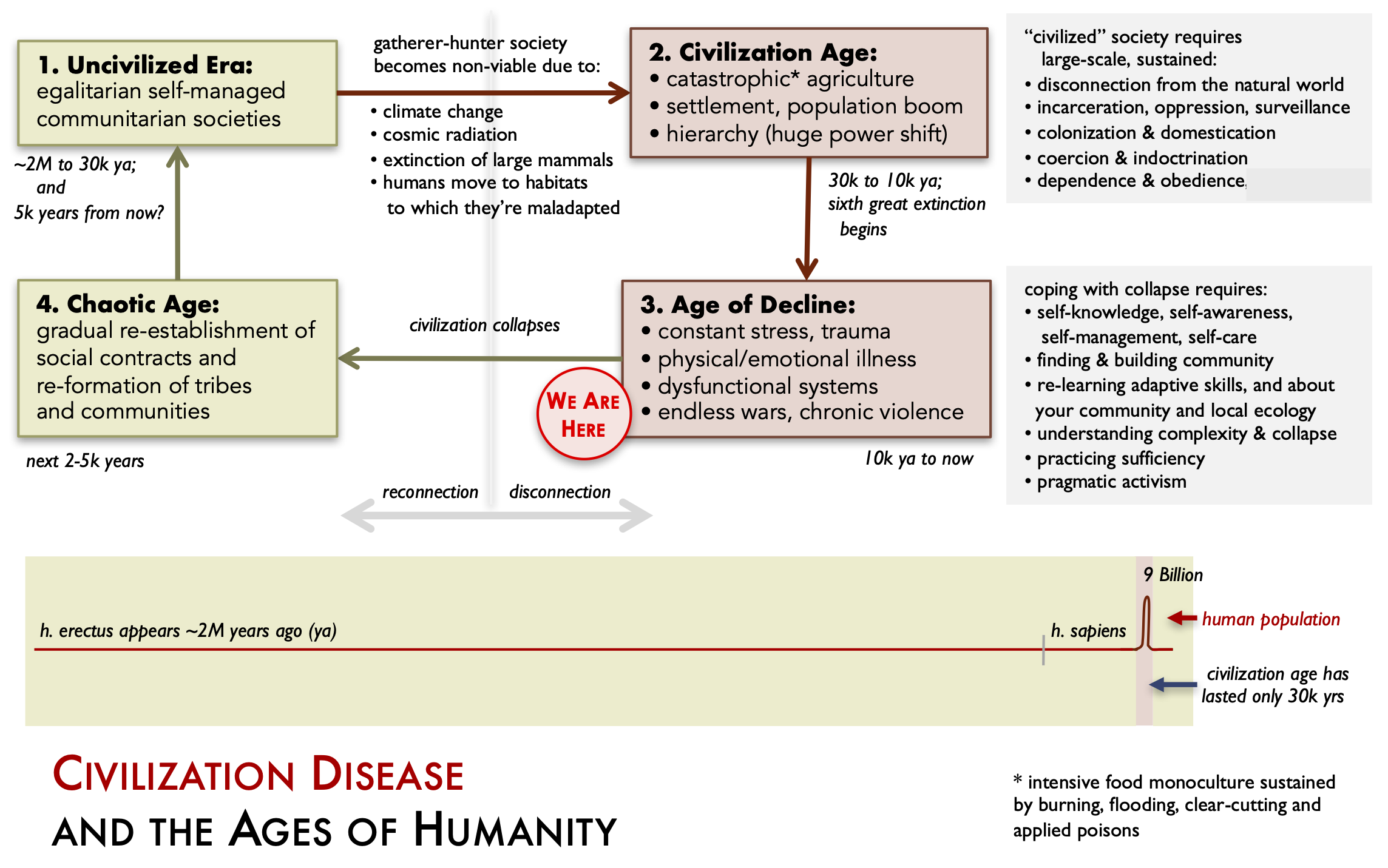

- The profound mental illness that this misunderstanding produced was expressed in some new behaviours, rationalized on the basis that they made the world ‘better’ by requiring it to conform more closely with the self’s model of reality as it “rationally” “should” be. These behaviours included subjugation, incarceration, wars and genocides, and oppression of those whose behaviours the self (and the other selves of emerging human self-afflicted cultures) could not make sense of, and therefore judged needed to be controlled. Language and new technology enabled humans to mass-produce food (“justifiably” using human and animal slaves), which resulted in an exploding human population, more pressure on limited and fragile resources and environments, and more physical and psychological stress on everyone, in a vicious cycle that continues to this day. Other new technologies (such as more powerful weaponry, and propaganda) exacerbated the cycle. It is this cycle that I call “civilization disease”.

Each morning when a modern human awakes, it has to recreate its story, built around its self, to make sense of how and why everything is as it is, how it “should be”, and what has happened in the past and might happen in the future. All of this is entirely made up, a fiction, reconstructed anew each day. Without this story the self cannot exist, and to some extent, the self is nothing more than this story.

How might this have come about? It’s conceivable, under the entanglement hypothesis, that humans are now born with the “necessary stuff” to concoct (imagine) a self, the representation of everyone and everything around it in time and space, and the story that is the self’s script, modus operandi, and reason for existence.

But it would seem that infants don’t have this sense of self or separation from everything ‘else’, or a ‘story of self’. The metaphor I have been using, for now (and it is a very imperfect metaphor) is that the makings of a self are like a piece of invisible VR headgear that we are (now) all born with, but which is initially turned off. At some point in very early childhood, our parents, anxious to give us a sense of self so we can function in the world, “switch on” the headgear, and suddenly we see this representation — of mother and father and “others”, of separate “things”, and then, astonishingly, of our “selves” as something apart from this seeming “everything else”.

It probably takes a bit of perseverance by the well-intentioned parents and others before the headgear is just left switched on all the time, and before the child learns to switch it on each time it wakes up, so that soon the child is no longer able to see anything outside the headgear, and ‘forgets’ there was ever another sense of what was real. The headgear was always invisible, always projecting only illusion, but now it is on, all day, every day, automatically, and it becomes the only reality.

As I say, it’s an imperfect metaphor, but it’s the best I’ve found.

It is, of course, excruciating that the self now begins to do things, to try to make decisions and control things, but what it sees happening through its invisible headgear just never matches up. It must furiously rationalize the reasons why this is so, why things are never perfectly the way they “should” be based on the model that instructs the headgear’s display. Why the controls of this game don’t seem to be working at all.

That means, for example, justifying war against those whose behaviour makes so little sense to the self that it must be labelled “wrong” or “evil”. Actions must be taken to make things “better”. And when things don’t go well, there is all the guilt and shame and hatred and blame and justification for why these selves, all of which are purportedly “in control” of “their” human bodies, are “misbehaving”. And, of course, there is fear and anxiety about all the terrible things that “might” happen, which our befuddled, integrated brains endlessly confuse with what is actually happening, making everything seem hopelessly, maddeningly out of control.

The people I know who are “no longer” afflicted by the illusion of self and separation remain perfectly functional, and seem to me more well-balanced than the rest of us. And I have no reason to believe that it isn’t possible for someone to grow up with the headgear of self never switched on, and no one would ever notice, least of all the unafflicted humans.

So back to the ‘story of self’. When I meet people who have suffered serious trauma, it appears to me that there is a ‘hole’ in their story. It’s as if the memories of what happened have been erased, or smudged. There is no peace in that, however — something in the traumatized self seems to be endlessly aware of this hole, and always trying to find some way to cover it up, to “make sense” of it, to make the whole story coherent.

And that’s what’s led me to believe that we (ie our “selves”) are our stories, and that is why people are always so desperate to have their stories make sense, and become dysfunctional when they do not.

I think, to be bearable, our “stories of me” have to meet two criteria:

- They have to be coherent and have continuity — they have to hang together in a way that can be understood (made sense of) internally and told comprehensibly and believably to others. I think most of what is said in human conversations is just the relating of our personal stories.

- They have to progress, or at least have a meaningful trajectory — there should be steady advancement, the overcoming of obstacles, and, if not a happy ending, at least a sense of valour in the trying. There is a reason that so many of our stories are ‘hero’ stories, about conflict, overcoming challenges, and success or at least redemption.

When I talk with people who have suffered trauma, I notice again and again the enormous sense of shame I hear in the incoherence, discontinuity, directionlessness, hopeless incompleteness, and personal, often unspoken ‘failure’ in their stories. There’s a desperation to fill in the holes in their stories, that seems as great as the unbearable trauma that must have caused the holes in the first place, and an equal desperation to evoke reassurance from others, and in their own minds, that their story is, at least, understandable, headed in the right direction, and redeemable.

There have been a number of analyses, recently, of our civilization’s psychological malaise as being a reflection of the sense of our collective failure to produce a coherent, positive story about ourselves as a society. The tagline for a recent documentary is “We have given up on the future”, suggesting that we no longer hope for a story with either progress or redemption. Our story is broken, and if we are our personal stories, our culture is our collective story, and it must meet the same desperate, demanding criteria.

“We need to create and tell a new story”, we are told. Why? Because without a compelling (in both senses of the word) story we are nothing. We are worthless, meaningless, purposeless. “We are seeing the rise of a world without meaning, a society without narrative coherence”, another essayist writes.

The invisible headgear, the story, the storyteller, the self, the experiencer and the experience are all one and the same thing. And they are a fiction; they are just the invention of a frenzied, deranged brain, trying futilely to make sense of everything.

At various points during my life I have tried to summarize “the story of me”. My lifelong, hackneyed, self-aggrandizing bios have recently yielded to an anti-story, one that is completely lacking in narrative and flow. As I described it last year, it is this, a story about ‘my’ relationship with this apparent human ‘Dave’ creature ‘I’ arrogantly presume to inhabit:

I remain forever tethered to pursuit of the impossible truth that will finally make sense of everything, finally bring an end to the exhausting seeking. I am in a corner, now; I’ve painted myself in after a lifetime of striving to complete the picture, the picture that my latest belief denies the very existence of.

So I sit here with my box of colours, brow furrowed, wondering what this perfectly, tragically conditioned (and only apparent) creature will do next; I have no remaining illusion that ‘I’ have any agency over it (though that may be just what ‘I’ want to believe).

I want to believe that if I’m tired enough, completely exhausted, my self, this lost, scared, bewildered ‘I’ that carries with it a lifetime of questions unanswered, a lifetime of believed truths unresolved, will just let go, set me free from me. I want to believe it, but I do not.

What happens when we can no longer believe what we want to believe, when we doubt that what we believe is actually true? Perhaps we just keep painting, even knowing the picture cannot be completed, that the canvas is just a dream. Like the carpenter with only a hammer, perhaps we keep hammering even when there are no more nails, when we discover, in the endless buzz of cognitive dissonance, that there may never have been any nails. Keep hammering, what we were made to do, and taught to do, and told to do. The only thing we can do.

It’s a really horrible story. Even Beckett would find it unacceptable. But I refuse to write a better one, a more accommodating, accessible one, with a good plot and tension and conflict and learning and redemption. I sit here, furiously shaking my invisible headgear and shouting “Fraud!” No more stories, please. They are worse than just self-glorifying fictions. They are lies, straitjackets, shackles, and the immiserators and scapegoats of our whole pathetic, ruinous civilization.

They are nature’s, and evolution’s, greatest blunder. They are the cause of our disease.

Dave I can read these story’s all day, there addictive.

What comes up is:

https://www.ted.com/talks/jill_bolte_taylor_my_stroke_of_insight/transcript

TL;DR

Neuroscientist gets a stroke and recognizes her predicament.

During the trauma, the sense of separation fall away.

If all the phenomena as we perceive them emerge from a more fundamental order, namely separationlessness (if that’s is even a word), we could never know or proof it. There no position outside of it that can point to it. Every story we have about it will generate an amount of cognitive dissonance. In that case the believe option is the only one we have.

More fun with nothing :)

https://news.fnal.gov/2021/02/random-twists-of-place-how-quiet-is-quantum-space-time-at-the-planck-scale/

Am I the only one that have a laugh if I read?

“In one sense the experiment was a big success, since we succeeded in measuring nothing with an unprecedented precision: With some kinds of Planck-scale jitters, we would have seen a big effect. But we found no such shaking. It was quiet.”

Gr Ivo

I’d only change the wording that “nature” is a something that tries things when that’s a projection of the human idea of having agency. So as an abstraction it can’t blunder. Even the story of evolution manages to imply “progress”. What survives causes all the species that died out to be forgotten – and some of these were around over timescales making this civilisation look the tiny blip it is. And I tiny sliver of this blip is our entire story and existence which we have to make important.

Yes, it’s only an apparent blunder, and only to the “me” that that apparent blunder produced. And the disease of course is also apparent, but putting “apparent” in front of every noun and verb we use would just be annoying, and wouldn’t make “me” feel any differently about it. Neither would acknowledging that “we” are only an apparent blip.