This is the 16th in a series of articles on CoVid-19. I am not a medical expert, but have worked with epidemiologists and have some expertise in research, data analysis and statistics. I am producing these articles in the belief that reasonably researched writing on this topic can’t help but be an improvement over the firehose of misinformation that represents far too much of what is being presented on this topic in social (and some other) media.

cumulative CoVid-19 deaths/M people, as at March 26, 2021, from OWID

I‘m less than two weeks away from my first vaccine shot, and, like most Canadians, have been told that my second shot could be as much as four months away. What I’m watching now is the rate of new cases, which has never dropped back to the low levels it reached last summer, rising again, despite a dramatic drop in testing, along with a commensurate rise in the percentage of new cases attributable to new variants.

In some places the new variants now prevail and daily deaths are again soaring (in Brasil to over 3,000 deaths a day). In most places cases are rising but deaths are falling. We have no idea whether that’s a time lag issue (it takes on average about 3 weeks between reported infection and death, for those who succumb), or whether it’s the relative mix of variants, or whether it’s because the average age of the infected (and hence the Infection Fatality Ratio of deaths-to-reported-and-estimated-unreported-cases — the IFR) is lower for this “wave”.

Befuddled politicians, for whom all of this is too complex and all that matters is the next election, are justifying reckless reductions in restrictions on the basis of the recent trend to lower death rates. This is guaranteed to ensure that cases will stay too high almost everywhere to allow test-track-isolate protocols to work — it’s impossible to keep up with new cases rigorously when there are more than 10 cases/day/M people. It was below that level in Canada last summer, and has almost never gone above that level in countries (Taiwan, Australia & New Zealand notably) that have dealt with the pandemic responsibly from the outset.

But now the rate in Canada is 112 new cases/day/M people (and 3% positivity rate) and in the US, where testing is down 50% from January levels, it’s 186 (and 7% positivity rate, suggesting they’re now catching a much smaller percentage of the new cases due to reduced and inadequate testing). In other words, after more than a year, the pandemic is still out of control here. And still we’re lessening restrictions when this is exactly when we should be tightening them — until at least 70% of the population is inoculated.

We’ve gone “all in” on vaccinations, and are counting on them, especially for older and high-risk populations, to keep the IFR down to politically acceptable levels before the new more transmissible variants spiral out of control and inevitably lead to a spike in new deaths. Will that strategy work? We have absolutely no idea. We are still, after a year of uninterrupted botch-ups in 95% of the world’s nations, absolutely clueless.

And now there are three huge mysteries that we also have absolutely no idea about:

- The IFR in most of Africa and Asia appears to be only about 1/10th what it is in the Americas and Europe (see chart above showing deaths/M people, a rough surrogate for the IFR). That is unprecedented in a global pandemic, and the modellers have had to scramble to slash forecast deaths for Africa and Asia to 20% of what they originally forecast. A part of this difference is due to demographics (a younger average age). But most of it seems attributable, as best as we can guess, to healthier immune systems due to better diet (and hence much lower rates of obesity and chronic “lifestyle” diseases) and much more exposure to other viruses in Africa and Asia. If this is the case, we can probably expect future pandemics to follow a similar pattern. If so, thank the western industrial food system, our obsession with putting antibiotics and other antimicrobials on everything, and our lack of plant nutrients and proper exercise; we are ripe for the picking. But we really don’t know.

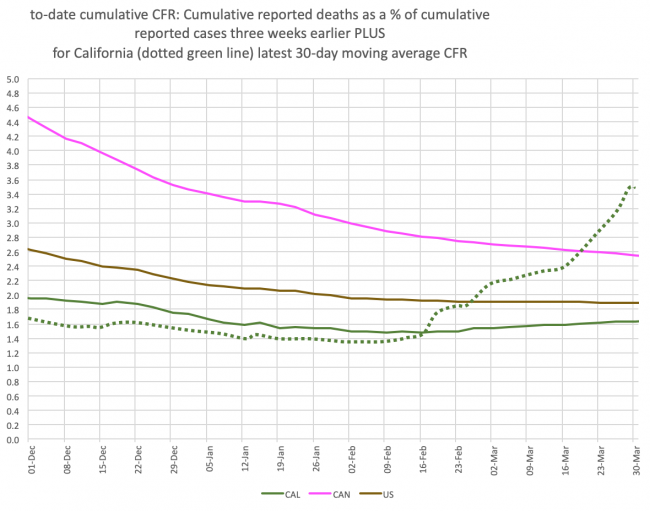

- The Case Fatality Rate (ratio of deaths to reported cases three weeks earlier) seems to have suddenly spiked in California to levels only seen in parts of Latin America that do very little testing (see chart above). Throughout the US, the CFR has been flat at 2.0% in the US for months now (in Canada, which did much less testing proportionally than the US in 2020, it’s converging on 2.5% but still declining). This suggests that the US has caught about a third of actual cases to date, and Canada about a fourth (most of the undetected cases were likely asymptomatic or very mild). But in California, over the last two months the CFR has suddenly jumped from 1.5% to 3.5%. While a part of this could be attributable to less testing, is it really reasonable to assume the state has suddenly gone from catching 40% of actual cases, to only 15%? Seems highly unlikely. Or perhaps they’re just now reporting “catch-up” deaths that actually occurred in prior months? More plausible, but so many, and why suddenly now? Or perhaps it’s a conspiracy to suppress case counts to cover politicians’ asses? Uh, OK, I doubt it. What is interesting is that California has the highest proportion of CoVid-19 variants (>75% of all cases) in the US. Though these are predominantly the B.1.1.7 variant, the NYT reports that the US is not yet screening for the P.1 variant that is ravaging Brasil and reinfecting and killing those who had recovered from the original virus and even those who had been vaccinated. The proportion of new cases attributable to variants is estimated to be doubling every ten days. So maybe the soaring CFR in California is due to unscreened variants, soon to be seen everywhere else? Possible. We just don’t know.

- The third mystery is the degree to which the vaccine protects us and others from various degrees of infection to the virus and its variants. The tests done to qualify use of the various vaccines have only tested efficacy at preventing any infection from the virus. The numbers of deaths and hospitalizations among those test recipients of the vaccines is so small that a statistically significant conclusion on morbidity cannot be made. We know the risk is very low (among the hundreds of rigorous phase 2-3 vaccine trial recipients, it is possible that there have been zero deaths), but we don’t know how low. It is likely that the variants, which are of three main types but dozens of sub-types, with new ones emerging quickly, present a higher risk of death or hospitalization, but we don’t know how much higher. And we don’t know whether some of those receiving the vaccine could still be mildly or asymptomatically infected and hence potentially “shedding” viral particles and infecting others.

The result is what Zeynep Tüfekçi calls confusing “absence of evidence” with “evidence of absence”. How long does it take, she asks, before the absence of any evidence that the virus is transmitted on contact with surfaces, becomes evidence that such transmission is extremely unlikely? We passed that point at some point in the past year, but we don’t know how or when, and it’s impossible to come up with tests that could produce useful statistics. Eventually, we just conclude, on the basis of absence of evidence, that outdoor activities, socially-distanced, are probably very low risk, and that it’s unnecessary to clean surfaces as long as you wash your hands after touching surfaces that have been “very recently” used by the public. Or perhaps it’s unnecessary to clean surfaces at all, given the lack of evidence anyone has ever been infected that way? The problem is, we just don’t know. There is no simple scientific process that can consider the millions of variables that can arise that lead to an infection, or the absence of one.

This is all leading to what vlogbrother Hank Green has said is a very worrisome sign for the rest of this year. We tend to believe what we want to believe, which means that, in the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, those (like me) who are convinced (want to believe) there is still likely a significant risk to themselves and others, are going to continue to wear masks, avoid non-essential travel and indoor public activities (like restaurant dining and bars), and generally continue to behave as we have until the local data on cases and deaths has dropped to the kind of levels seen in Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand. And those who are convinced (want to believe) that vaccines confer absolute immunity and the pandemic was overplayed anyway, will quickly and enthusiastically go back to their pre-pandemic behaviours, if only to prove to themselves and the world that this belief is correct.

What Hank is concerned about is that this will result in what might be called “Mask Wars” for the rest of this year. Our mask, or absence thereof, will be seen by “the other side” as a political statement, and as a judgement of “the other side”, provoking the kind of visceral reaction that could conceivably lead to the kind of violence and animosity that other “symbols” like certain clothing, haircuts and body markings, and in-your-face T-shirt and hat slogans, have occasionally produced.

I know that, long before CoVid-19 arose, when I would see people walking on the streets of Vancouver wearing masks, my reaction was, I’m ashamed to say, judgemental and not positive. It made no sense, but it struck me, on our clean, healthy streets in the old days of 2019, as a kind of political statement of my city and its people. So I kind of “get” the anti-maskers’ reactivity, and the potential for it to get nasty as the pandemic wears down, and wears us down.

This will be especially hard on us mask-wearers, since the trend will, inevitably, be in the other direction, and the smaller a minority we become, the more threatened we may feel (and be).

But perhaps Hank and I are needlessly worried about all this. Maybe we’ll just be viewed as quaintly out of style. Maybe the approaching end of the pandemic will bring relief and healing instead of increasing the anger and division.

We just don’t know.

Dave, how about the low IFR in Africa and Asia being partly due to higher levels of Vitamin D. Did you consider that as a possibility?

I guess it could be a factor. If it’s about sunshine, though, I would have expected minimal differences between Africa and South America.