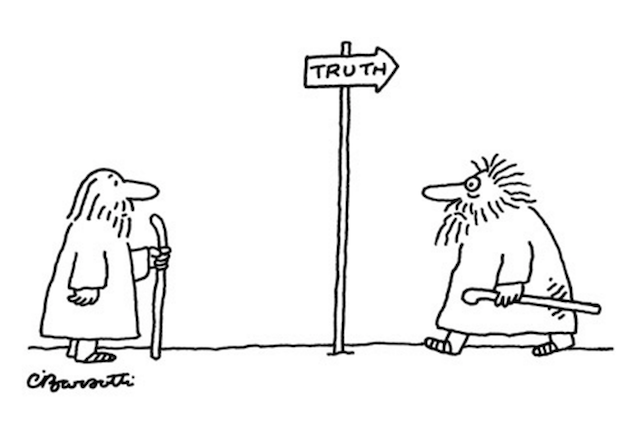

cartoon by the late, wonderful Charles Barsotti

Lapsus (L. adj.) falling into error; in rapid decline

It seems that most of the people I know, especially men, as they get older, and learn and know more, become more and more unhappy, despairing, even depressed.

Depression dominated much of my youth and middle age, and now, as I get older, I just realize more and more how little I know, and I grow happier, more often astonished, and gradually more equanimous.

While the knowledge that our global human civilization is in its final, potentially horrific, century is enough to bring out denial and despair in most of us, the realization that this destructive civilization cannot be ‘saved’ was, for me, absolutely liberating. The end of our civilization is a cause for rejoicing, not despair! It’s a chance for our little blue planet to heal from all the damage our species has unintentionally inflicted on it, and, once collapse is complete, it will bring the end of our human suffering and, maybe, a chance for future, smaller, human societies to thrive as a part of, rather than a destroyer of, the Earth-super-organism that some call Gaia.

So we are a wretched species, but not because we’re evil, or innately ruinous and catastrophic, but because we’re afflicted. We are not well. Whether our species perishes like a cancer, victim of the damage it’s done to its host, leaving the planet to recover in its own, astonishing, five-billion-year-old way; or if, instead, the human animal survives as a bit-player in a rebalanced, whole, healed planet, the suffering will soon be over. Maybe even in less than a million years, a blink of the eye in cosmic time!

How can one be depressed and despairing at that realization? For our planet, and perhaps our species, the most interesting and peaceful millennia are likely still ahead of us.

The uniquely human affliction I refer to above, for those not familiar with this blog’s (latest) thesis, is the disease of self-hood, the ghastly, illusory, hallucinated sense that we are, each of us, apart from the whole of all life, of everything that is, and that, worse, each of us is responsible for the miserable lifelong struggle to survive, and to somehow make things better. And that we have free will and control over the body of the creature we presume to inhabit, even when it misbehaves. And that the consequences of that misbehaviour, and of all human behaviour, are real, solid, and etched in history’s unsympathetic, unsparing record. All an illusion, a misunderstanding, a mistaking of our brain’s fevered conceptualizations for reality.

This illusion of self-hood, separation, ‘consciousness’, finity, and control, is like a worm that has burrowed into and infected our brains. It makes us see and believe things that are not real or true, and, since it’s a contagious disease endemic to all humans from a very early age, we all inadvertently reinforce the credibility of the illusion to each other. When we all see the same hallucination, that makes it hard to deny, but that doesn’t make it real.

The vehicle for transmission of this disease (though it is a mental illness, not a virus) is our stories.

And oh, how we love our stories! When we were tiny infants, there were no stories, and no time or space within which they could be situated. But then suddenly there was this sense of self, of being, somehow, apart, and simultaneously everything else separate from ‘us’ was also seen as apart. And the story of our selves began.

And from that point on, there was a thirst to ‘know’ — to hear and make sense of others’ stories, to see how they meshed with our stories, and where they agreed and disagreed with our own. “Why?” and “How?”, we incessantly asked our parents, the first ‘others’ we recognized and heard stories from: “Help me make sense of this story.”

Some of the stories were astonishingly beautiful: The story of humanity’s fall from grace by eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge. The stories of wise and foolish talking animals. The lovely unfinished mystery story of evolution.

And then there was the indoctrination of school, where we were told which stories were correct and which were not, even though we continued to harbour a sense that they were all just stories anyway, so what did it matter whether they were approved and verified, or just made up? We heard the stories of historians and scientists and others about how things were and are and worked. And, as we all know, if you hear a story often enough, from enough different people, you start to believe it’s true.

But something has never rung quite right, for some of us, about all the stories, especially the ones about responsibility and self-control and “you can do anything you set your mind to” and the whole story about progress and the striving to make things better. No matter how often we heard these stories, some of us couldn’t quite buy them — they just didn’t mesh with our observations. Surely life shouldn’t have to be this hard!

And these dissatisfying stories created a lot of anxiety and fear and grief and sorrow and anger and rage and guilt and shame about the gulf between what “should be” and what seemingly actually was. Damn those stories, anyway! According to them, we’ve never been and never will be good enough, deserving enough. Our foolishness, bad judgement, our failure to be smart and educated and knowledgeable and popular and loved and rich and successful and recognized and healthy (physically and psychologically) and attractive and listened to and appreciated and reassured — these stories imply that these failings are all our fault. And they don’t seem to be our fault because we’ve tried our best and done what we were told. It’s unfair! It must be someone else’s fault, and surely those people need to own up to their error and make it right. Someone’s not telling us the truth.

And then there were the love stories. The ones we were told (by people we know, and in books and on TV and in movies and songs) were compelling. We wanted to believe they were true. But the people telling them were on drugs. Of course, when we fell in love ourselves we forgot that the feeling was just a combination of intoxicating chemicals that our bodies manufactured to compel us to mate and stay with other humans, and so we started to tell, and to believe, our own love stories. They became the most important stories of all.

Our stories about love proclaim that love, and only love, can redeem us, and make all the anguish and anxiety of our stories of ‘me’ subside. And they shift, for a while, our attention from our own stories to our stories about those we love. Of course, these are still our stories!

But the love stories turn out to be dubious as well. Keeping the illusion of mutual, unending love for another human alive turns out to be hard work, a kind of internal complicit con job. We want to believe that we still really love and will always love these people we said we would always love. But the drugs that compel these proclamations, these forever stories, wear off, and the stories become harder and harder to believe, or to convince others of. “If you really loved me you would…” then becomes a kind of shaming, a desperate accusation that the story we had told was untrue, or that (if we are the one let down) the story they had told us was untrue. Why would anyone lie about that?

And those other love stories, about loving our god or our country or our Party or our possessions, or our selves, are so desperate and lame that we kind of feel sorry for anyone that believes them.

Suspicious of stories, now, some of us turned to other drugs, those we thought we could depend on to make us feel better, the way the stories said we should feel. They were very good for a while, but coming down from them and falling back into the story of our “real” lives was hell.

How could we get home, to that wondrous place before all the sad, invented stories began? We tried all the paths — riches, popularity, excitement, pleasure, work, sacrifice, devotion, therapy, spiritual enlightenment — but they all led back to the infinite closed loop of us.

So now there are no paths, no escape. We are alone with our disease in the prison of our self’s own making, in the unholy mess our species has so quickly made in its distress and despair. What we observe through the headgear that we innocently put on in early childhood, and which we now cannot even see to take off, is the only truth we know, the only life we know, the only life that we can know.

Is it enough to know this? Is it enough to know that the future, which is just another story in any case, will be, without us, wondrous, magical? That as there is no time and no “we”, the apparent death of what we call our selves will be just as much an illusion as the life that apparently preceded it, changing nothing except, perhaps, the illusory burdens and grief of those we seemingly leave behind?

Is it enough to know that this is all just an amazing show, nothing appearing as everything, already, without meaning or purpose, and that it’s only we wretched afflicted humans that can’t see that, but that, one way or another, the headgear that constrains us will soon be wrenched away (though not as a result of anything we do) and all will be revealed?

Maybe, for some of us. For most, it will remain as ludicrous as Copernicus’ heliocentric argument was for two centuries after its publication — absurd, ignorable, obviously untrue, a truly incredible story. A tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.

We will see.

Is it enough to know this? Is it enough to know that the future, which is just another story in any case, will be, without us, wondrous, magical?

“Wondrous” and “magical” are uniquely human adjectives (probably) and the future won’t be like that without us using those words. It will simply be as it will be. The universe doesn’t care whether the surface of Earth is like it is, wondrously covered with life, or whether it is like the surface of Venus, what we humans would call a hellhole.

We humans have evolved to tell each other stories, to have a sense of self, of love and all the other emotions we feel as beings with complex social behaviors. For the past few hundred thousand years that evolved nature has had quite good adaptive fitness. Now, not so much.

If the earth had no fossil fuels our nature would most likely still be perfectly adaptive. It was just our bad luck that we discovered a resource that was capable of creating a modern industrial civilization. We will just have to live with the consequences, or not.

My story is to try help my family and others live through the end of that civilization by upping the odds of survival just a little. It may not “save the world”, but it will certainly continue to help my mental state, illusory as “my” mind may be.

Thanks Joe, well said. There is some evidence that the sixth great extinction began its current trajectory with the disappearance of many of the planet’s large mammals. So it could be that the end of our capacity to ‘fit’ with the rest of life on earth was the result of our invention of the arrow and spear, rather than the more recent discovery of abundant burnable hydrocarbons.