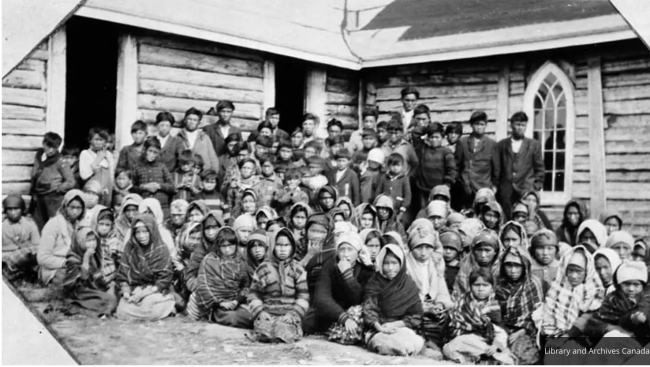

child prisoners of the Kamloops Roman Catholic Indian Residential School, which operated 1890-1960; 215 children’s bodies have been found through ground-penetrating radar photographs on the grounds of this “school” alone; photo by Library and Archives Canada

My friend PS Pirro recently wrote a post called ‘Hiding the Dead’, cataloguing some of the stories of how our species, with official sanction and impunity, has regularly murdered, and anonymously and unceremoniously buried, its most powerless — notably indigenous peoples, “slaves”, “minorities”, police detainees, prisoners of war, inmates of “detention centres” and other institutions, the poor and sick, and women and children.

The recent discovery, using new ground-penetrating radar technology, of the unmarked remains of thousands of young children torn from their homes and forced to live in brutal conditions in religious brainwashing “residential schools” — their bones found right beneath the “school” grounds — is just the latest example.

We are also, seemingly, taking the first, wobbly steps towards reckoning with the legacies of slavery, apartheid, caste-ism in all its variations, and genocide, and the long-ignored questions of reparations, and “truth and reconciliation” are now being asked more openly, with long-suppressed outrage.

I wrote in response to Peggy’s post:

Perhaps the big surprise to me is not that these atrocities were happening and we never knew (because we didn’t want to know, didn’t want to believe it was true), but rather that now, when everything around us is in free fall, we are for some reason suddenly willing to start to acknowledge that they happened. The interesting question to me is “Why now?”

As extreme weather events, pandemics, wildfires, infrastructure collapses, proxy wars over land and resources, water shortages, and inequality all continue to accelerate towards inevitable economic, ecological and civilizational collapse, this would seem an odd time to be reflecting upon past and continuing injustices.

But is it? Is our global civilization culture now recognizing, and sensing instinctively, that these are end times for our culture if not our species, and beginning a kind of death-bed repentance for what we have done that has led to the point we’re now at?

Perhaps it’s just wishful thinking on my part, but my sense is that this is what is happening — a reckoning with our inhumanity as our tyrannical reign draws to a close.

In The Waste Land, Eliot writes: “Shall I at least set my lands in order? | London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down”, an allusion to the biblical proclamation “Set thine house in order: for thou shalt die, and not live,” and to the song about a bridge that falls down despite all attempts to prop it up. I’ve known quite a few people (including many politicians) who have, late in life, acknowledged that while it is too late or they are now incapable of correcting their errors, they admit quite remarkably and ruefully to their folly.

And yes, it is mostly too late to undo, mitigate or make amends for these egregious behaviours. The damage is done and cannot be undone. We will be hard put to make use of what remains of our shattering civilization’s remains* to prevent extreme hardship to the 7.8 billion people completely dependent on our vulnerable global systems for their survival, let alone atone financially to those who have been oppressed in past and continue to be so today.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t reckon with it, and admit to it. We can still tell the truth, admit our culpability, and genuinely grieve for the victims (human and more-than-human) of our ill-advised, run-amok civilization — even including ourselves in that list of victims to some extent. To admit culpability is not to admit intention to do harm, regardless of what the $^%# lawyers might tell you. “We were really doing what we thought was best”, is not an excuse, but it is an explanation.

We can at least attempt to understand why we were so misguided as to believe our atrocious behaviour was “best”, and convey that to its victims. We can at least listen to what that behaviour has caused for its victims, and acknowledge its truth, and attempt to learn from it. What matters most is the listening, the acknowledgement, and the learning.

And, while short of making reparations, there are opportunities for restoration — to return some of the lands and property that were egregiously stolen to their owners and their heirs. That is the least we can do.

A death-bed repentance is not necessarily a plea for forgiveness or even understanding. It may even be a completely selfish act. But once we give up the belief that we can and must “progress” forward, and that we dare not admit the weakness of past errors for fear of retribution, we can at least come to grips with what we’ve done more fully and honestly. There is some evidence, in the ruins of past civilizations, that such a broad-culture acknowledgement of what went wrong (perhaps in the hope future generations would not repeat the errors) has been made and documented.

I would like to see our global industrial civilization culture create such an acknowledgement, a collective, full and truthful reckoning of our mostly-unintentional folly. When our feeble and useless attempts to mitigate climate, ecological and economic collapse utterly fail in the next few decades, such an acknowledgement may be all that is left of use to those our crumbled civilization leaves behind.

At the end of her post, PS introduces her word of the day: Procrustean, named after a mythical ancient Greek abuser who stretched or amputated his victims to fit his torture bed. The word means “violently making conformable to standard, producing uniformity by deforming force or mutilation.”

PS concludes brilliantly by summing up the true meaning of this word: “We made your bed. Go lie in it”.

Xenophobia, which is now the lifeblood of conservative politicians just about everywhere, means “fear of what is strange or different”. In times of great upheaval, change happens faster and becomes strange and different more quickly. There is therefore much more for xenophobes to fear.

That is what, I think, is happening now. We are not a very resilient or naturally adaptable species. We are physically suited to a very narrow range of ecosystems and ways of living, so whenever we move outside that comfort zone, our approach is to conquer, to destroy, to terraform, to make the world and its “strangers” fit what we want, and live in a fragile, prosthetic world of our own making, rather than adapting ourselves to the world and its “strangers”. We want them to lie in our Procrustean bed.

That is perhaps why, since our species left our birthplace in the trees of the tropics, we have become so violent, war-mongering, territorial and destructive, everywhere we go and in everything we do. We desperately have to make the world “fit” to our narrow definition of what is liveable, right and good.

But I don’t think that’s our true nature. I don’t believe our slow, chisel-toothed, clawless species was ever meant to stray beyond our homes in the trees, to leave behind our bonobo-like passive, easy, lethargic lifestyle, or our ancient vegan diet (there is evidence that for our first million years, the largest single component of the human diet was — figs). Our modern human behaviours are a sudden aberration.

We are, as I keep saying, not well. So yes, we are cruel, but that is a symptom of our disease, not our genes. And this disease is rapidly burning itself, and us, out. I would like to believe that we could one day acknowledge that, and leave our reckoning with our inhumanity, with at least a trace of humility, as our epitaph.

* As an aside, I am increasingly convinced that we are quickly heading towards a war between the richest 1% (and their propagandized lackeys), and the rest of us. As our crisis deepens, it is inconceivable that the current obscene level of inequality can hold. During the Great Depression, taxes on the rich and on corporations jumped to 90% to finance the various New Deals that redistributed wealth dramatically when it was needed. We’re going to see that in the next decade or so, I am convinced. It’s not going to be easy, or pleasant. And this war has already begun.

There is a war already ongoing – and has been all along. The dominance paradigm that emerged along with humanity leaving tribal hunting gathering to go to agriculture. The trick of dominance is to have it exerted as invisibly as possible. The children in your story have been invisible. Maybe with better understanding, the printing press and internet this invisible dominance is becoming ever visible.

That’s the thing about healing wounds to the soul. When it is time for healing they start to hurt, and the hurt grows until the wound gets tended.

The dominance paradigm – explained nicely by Riane Eisler and Aldous Huxley explains how the stressed society (cramming people into cities) gives rise to the desire for the good order (Fascismen) – will have to end one day, when humanity is ready to heal people will get fed up with it and walk away – even the rich.

Another excellent post, Dave! I just read it aloud to Connie and she loved it, too.

On a totally related note: a book that I only read last month for the first time, and which I highly recommend precisely on the subject of this post, is Jack D. Forbes’ classic, “Columbus and Other Cannibals: The Wetiko Disease of Exploitation, Imperialism, and Terrorism: https://www.amazon.ca/Columbus-Other-Cannibals-Exploitation-Imperialism/dp/1583227814/

It is one of the most significant and troubling books I have ever read.

We are physically suited to a very narrow range of ecosystems and ways of living

There is much to agree with in this post, but I think the quoted sentence above is exactly backwards. Humans are perfectly capable of living in a very wide range of ecosystems and learning considerably different ways of living (cultures). Our discomfort with that difference gets expressed as zenophobia.

But why are we uncomfortable with cultural difference? It’s because cultural differences are a marker for the territoriality that inevitably accompanies the search for food and reproductive opportunities.

All human tribalism is based on competition for resources. The more limited resources are, the fiercer the competition. This should be no surprise, since competition for food and mates is found everywhere in the living world. It is one of the key drivers of evolution itself and since the world is full of variety and multiple opportunities for acquiring needed resources, cultures can develop in bewildering variety.

You are right that we fear this variety and react strongly to differenct cultures, but our modern behaviors are not a “sudden aberation”, they have always been enabled by our genes. Welcome to the living world.