In Part One of this article, I described the global economic forces that have largely defeated Bowen Islanders’ attempts to create a sustainable, livable, long-term home for its diverse, long-term residents. I explained that the only future for the Vancouver exurban island I can now see is as a combination of a multi-millionaires’ playground, a retirement sanctuary (for those pension- and property-rich enough to afford it), and a grinding commuter bedroom community for those with young families. I predicted that the underclass of local workers and artists will be slowly forced out.

This is a shame, but it reflects the reality faced by many similar exurban communities near the world’s most desirable cities. There is no easy, or local, fix.

In this part, I want to talk about what it means to be a true community, and how I learned so much about what community really means from Bowen Islanders.

Many of the 20 sq. mi. island’s residents (and ex-residents) came here looking for sanctuary, and saw its relative isolation as a benefit, not a drawback, to living here. It contains the largest forested area of Metro Vancouver by a mile, and is so popular with day tourists that their arrival in summer wreaks havoc on ferry traffic, with commensurate overloads, delays and disruptions to schedules.

Islanders are heavily dependent on the ferry — travel by and on it constitutes half of the island’s total carbon footprint, and the ferry is essential for most jobs (about half of the adults on the island commute to the mainland), and for most purchases, including many foods.

The island is mountainous. Its three largest mountains, 1300-2400 ft in elevation, take up nearly half the island’s area and create rapid runoff of rainwater and soil; dry wells and low lake levels are a recurring and worsening problem. The very hilly terrain, and the sprawl of subdivisions around the perimeter, make travel by bicycle or on foot impractical, unpleasant, and sometimes dangerous for most. The island’s soil is volcanic, which is not great for growing food, and the richest growing areas, in the valleys between the mountains, have been paved over and built upon.

So the island is, except right in the cove where the ferry docks, heavily car-dependent. The ferry dock on the mainland is another exurb, which entails additional transportation by car or bus once off the ferry, to get to Vancouver itself. And when you return you may well find yourself in a convoy of dozens of cars, each with a single passenger, crawling along the cross-island roads, stuck behind a bicycle, slow-moving car or construction vehicle (passing is not possible on any of the roads, due to their narrowness, steep ditches, blind hills and sharp curves). You can expect waits in the ferry lanes averaging 40 minutes going both ways, in order to make the 20-minute-long crossing. As I write this, there have been overloads and/or 20+ minute delay alerts the last sixteen days in a row.

But, if you want to live in a paradise, it can be worth the hassle. The 100-car ferry trip itself is, pandemic notwithstanding, delightful, and scenically stunning. The island’s forest and/or ocean views, from most houses on the island (there are very few apartments), are enchanting. If you’re not in a hurry, or in urgent need (the island has very limited medical services), it really can be a place of sanctuary, with the ferry home a kind of decompression chamber.

It’s a do-it-yourself kind of place. Lots of home-made additions and projects on the mostly-sizeable lots, many of which have proceeded without building permits since they’re secluded from view. Islanders will help you if you ask, but otherwise they will leave you to your privacy and your own devices. That includes dealing with often-frequent power outages (lines are above-ground in heavily-treed areas), storm damage, treacherous conditions when the ice and snow comes, especially on the hills, rain damage, insect and rodent infestations, water supply problems, sub-zero temperatures (most homes rely on electrical, gas, oil and wood heat, each with its own supply vagaries), appliance breakdowns, and medical issues (there is an ambulance service but no 24-hour clinics, and the closest hospital is a ferry/helicopter trip to the mainland away.

And if there were a significant forest fire, catastrophic windstorm, or earthquake/tsunami, well…

At one time, most islanders took this in stride, and were quite self-sufficient. But newer arrivals (like me), who are used to being able to flip open the ‘yellow pages’ and pay for any desired repair and maintenance services quickly, can find it nerve-wracking. I could feel my blood pressure rising on cold icy nights when the lights began to flicker.

What I learned, though, is that this presumption of self-sufficiency does not mean islanders don’t care about or help each other out. But since it’s a very ‘British’ culture, it does mean that you have to seek out your neighbours and others in the community, let them know what you can handle yourself and what, under some circumstances, you would need help with, and what you can offer in return.

In short, it means if you want to be part of the community, you have to ask. You can’t expect your neighbours to show up at your door with a welcoming bottle of wine and an open invitation to drop by (as just happened this week when I moved to Coquitlam). But if you need something, and ask, almost assuredly if the person you ask can’t help you themselves they know exactly who on-island can.

My first experience of community was in a small village in Belize, during a visit with Joe Bageant. There, when young people paired up and left their parents’ home, the whole family and neighbourhood pitched in to find a piece of land, build a small house, and hook it up to the local utilities. There, if there was a (rare) crime, the community knew exactly who was likely responsible, tracked down the perp and forced reparations. There, if there was a medical issue, they knew who to call, and the issue was dealt with quickly. There, orphans and homeless people were simply adopted, by community agreement, and the duties of looking after them were shared. There, everything from tools to TVs were shared, even if they were in a family’s home — doors were always open, and borrowed items were promptly returned in good condition (or passed on to the next borrower). As Joe never tired of saying: Community is born of necessity.

It was not a utopia, and it wouldn’t work in our culture, but it worked, and it was very instructive. Nine-year-olds there knew how to do and fix things that in our infantilized, dependent culture most adults are clueless about, and they learned mostly by just watching and paying attention.

So why, you may be thinking, do I say I learned so much about community from my 3800 fellow Bowen Islanders during the twelve years I lived there? It’s mainly because, while the residents of the Belizean village knew how to do things for themselves and each other, and most of those in our modern northern cities have no idea, the residents of Bowen Island knew (or learned) what they didn’t know, and they knew who did know. Or who would know who did know.

They knew who had an AWD vehicle to get to and transport an accident victim stranded up an icy hill. They knew who had what power tools, who could fix an old computer, and which local repair people to trust and not gouge you (and thanks to word of mouth, the incompetent and the gougers quickly went out of business). They knew who knew about ailing fruit trees and how to make and can jam and how to select and install solar panels and how to deal with bats in the chimney and moths in the cupboards and fruit flies in the kitchen.

When you live on an island with only 190 people per square mile (a tenth the density of Vancouver), with the daytime-only ferry between you and the rest of the world, you know who you can turn to, no matter what happens. And if you don’t, or don’t want to ask, and aren’t self-sufficient, then you probably self-select off the island.

It’s a strange thing, this reluctance to ask, to admit you can’t completely look after yourself. We’re used to picking up the phone and calling people who know, and we pay them for what they do. So we have this illusion that we’re self-sufficient, an illusion we essentially buy. In previous places I lived, I had a list of suppliers, and when they didn’t come right away to do or fix what needed doing or fixing, I complained that “you can’t get good help anymore”.

On Bowen, instead I had a contact list, of people on island who knew who knew what to do. I had to call them, confess that I ‘needed’ help. It was uncomfortable. But it’s essential learning about what living in community means. Having become used to being considered a success and an expert in my field, admitting I ‘needed’ help was like an admission of failure (and, indeed, one islander, responding to a post from me suggesting we needed an online list of local suppliers for every imaginable situation, described my post as ‘pathetic’).

An eye-opener for me was Bowen in Transition’s Sharing Circles (aka Gift Circles). These events, which entail people taking turns saying to the group what they have to offer for free (surplus or lendable stuff, a particular skill or talent, free time, a shareable space etc), and then what they would love to receive but don’t know where/how/who to get it from. And then, one on one, where there’s a match the potential sharers and receivers chat and make arrangements. These events are designed to encourage more candour and comfort in acknowledging what we need (or just want), and more self-awareness and generosity in what we could offer others at little or no cost, but don’t normally think to find out if they would be useful to the community.

As I noted at the time:

There was considerable initial reluctance from some [Sharing Circle] attendees who thought the process intimidating and a little too intimate for them. In fact, a few people who were put off by the description of the activity chose not to come to the meeting at all. But the reluctant attendees participated enthusiastically and said afterwards they were absolutely sold on the value of the process.

This is what community is all about.

And it’s about:

- Potlucks: When I arrived, a bachelor, on the island, I got three invitations the first month to potlucks from the small number of people there I already knew. I didn’t even know what potlucks were, and was anxious about what to bring, and how much. But I figured it out. There are no rules, but in true communities, they always seem to work out.

- Adapting in Place: The nature of any successful community depends on an appreciation of what’s available locally (natural and human-created resources), and on the skills, capacities (including time and space), and needs of the members. If there are more needs than available skills and capacities, and a mismatch between them (as is true in most places) creating community will be a struggle. Adapting the community to the place enhances it; terraforming the place to suit the community members destroys it.

- Always thinking about doing things for others when you do things for yourself: On Bowen, many people would never think of taking a trip to the mainland without first canvassing several community members to see what they could pick up for them while they’re over there. “I’m going anyway…”.

- Shared labour: As with true ‘work bees’, real communities ask others to help them do the work that needs to be done, rather than hiring. My Bowen friends Mike and David helped me disassemble and pack my treadmill desk (with a stripped bolt, yet) — a really tough job that ended up needing tools I don’t own. Did I feel guilty about asking them? Yeah. But I got over it. I still tend to keep a mental ‘ledger’ of what I’ve done for others vs what they’ve done for me. But in real communities this isn’t an issue — you learn who asks for too much and offers too little relative to their capacities, and then you learn to say no. Which is almost as difficult for most people as learning to ask.

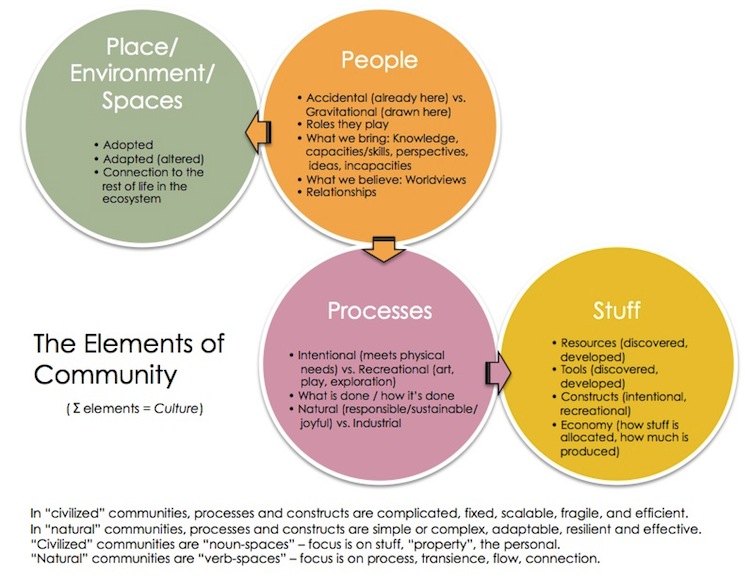

- A motley mix of ‘accidental’ and ‘gravitational’ members: Communities have a mix of people who ended up there by accident and those who were drawn there and went there purposefully. You need both. If all your members are gravitational, you may have a cult instead of a community. If none of your members is gravitational, it may still be a community, but it will likely be an unhappy and un-cohesive one.

- Self-managing: Local governments often try to ‘manage’ and mould successful communities by offering amenities like community centres, neighbourhood groups etc. These can be very valuable resources, but they will only work if the community embraces them as their own, and if the community members collectively manage them to meet their needs. And they won’t know what they need until they try things out and tinker with them. The world is full of infrastructure and tools that people thought were needed but actually weren’t.

- Play: You can’t stay a cohesive community unless it’s fun and relatively easy. If keeping the community together is work and arduous, the organizers are going to begrudge doing it. In intentional communities, they figure out how to dole out and simplify the un-fun work (clean-up, finding volunteers, dealing with delinquent kids and pets etc).

There aren’t many examples of sustained, successful communities to draw on. But I’ve seen a few intentional communities, thanks largely to Kavana, that continue to adapt and evolve and show us the way. And Bowen Islanders have taught me so much about how communities can work, even though that learning may mostly be lost if the island is overwhelmed by development and ‘market’ forces.

Thanks to all my Bowen peeps for showing me what’s possible.

Hope you’ll find community in Coquitlam, Dave!

One day, we’ll chat about how community works on Kauai…

Meanwhile, my book lays out an idealized version of Kauai community governance.

Oh, and, hope to cross your border one day soon…