(This is a thought piece. It’s far too late to reform our political or economic system, but it might be worth thinking about how and where we went wrong, and what a better system might look like.)

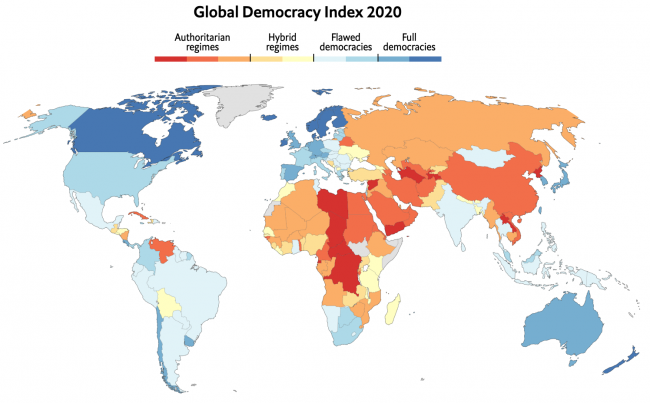

Democracy index from The Economist. Another recent international survey suggested that only one in four citizens under the age of 40 consider it essential to live in a democracy.

Despite the popular myths, it’s likely that early tribal humans, far from being hyper-hierarchical, made decisions collectively, though they respected the right of individuals to do their own thing, as long as those personal actions did not negatively affect the group. Those decisions were made, probably even before language evolved, by the subordination of personal interests to the collective interest of the tribe. But they listened to and respected dissenting voices. The collective decision thus emerged, from listening, until there was a clear consensus. There was no need, or space, for debate, or voting.

Of course in those early days many decisions were made instinctively rather than by consensus, and most of the decisions to be made were fairly straightforward.

There’s a famous story of three Inuit tribe members who get stranded in a blizzard during a hunt. They discuss their situation. The two elders say their experience and instincts tell them to stay put and wait for rescue. The younger hunter accepts the argument but states his belief that it would be best for the group if one of them were to attempt to make it to safety and tell the rest of their community about their predicament. Finally the younger hunter heads off. In the end, the elders are rescued and the younger man dies. There is no blame, no repercussions, no second guessing the decisions. The choices were the only ones the trio could have made in the circumstances. They were respected, the young man’s death was mourned, and life went on.

At this scale, tribal decision-making might be termed a form of direct democracy. Everyone who wants to have a say has one, and a collective decision emerges by consensus, but it is not binding on anyone, unless an individual who ignores or defies that consensus clearly significantly disadvantages the rest of the group.

Direct democracy, kind of, would thus seem to be how human tribes made decisions for most of our time on the planet. It probably isn’t even a stretch to suggest that herds and flocks of many other animals use a form of direct democracy in making their decisions. Again despite the myths, “alphas” do not make decisions for others, “leadership” roles rotate regularly, the “law of two (or four) feet” tests the group’s readiness for consensus, and principles such as the “first follower” enable wild creatures to reach a decision in their group’s best collective interest. Dissenters and unpersuaded group members are free to go off and look for another group, except at critical times (such as breeding season, or when under attack), when all members of the group instinctively pitch in to share the extra burden or workload, or help work through the crisis or challenge. We’re not so different, or, at least, we weren’t.

As human societies evolved in size and complexity, it became impractical to involve every community member in every significant decision. Decision-making was then bifurcated —

- Some decisions were delegated to specific individuals or roles, where the decision-maker was given both the responsibility and the authority to make decisions for the benefit of the whole group, without direct or continuous oversight; and

- Other decisions were delegated to representatives who were selected by some process or other by the community to learn enough about a complex problem to deal with it more effectively than the whole group could, since the whole group would not have the time, knowledge or experience needed to understand enough about the problem to make a decision competently.

This is the start of so-called representative democracy. Arguably, it has never worked well, and has become more and more dysfunctional as the representatives have become further and further removed from the constituents they presume to represent, and as the issues have become so complex and plentiful that no one can hope to be knowledgeable enough to make competent decisions about them. This is the point at which highly complex societies start to collapse of their own weight.

At the same time, our whole sense of community has been lost as the requirement of modern societies rely on us living in anonymous neighbourhoods with people we don’t know or share much of anything in common. Who are these representatives presuming to represent anymore anyway?

So now we have self-important elected full-time politicians whose only competencies are public speaking, spreading propaganda and misinformation that advances their re-election prospects, and taking money from wealthy and powerful interest groups in return for rubber-stamping regulations and laws that favour those interest groups over the interests of the supposedly-represented community. It’s no wonder that fewer than half of citizens can be bothered to vote, and that most of us who still do, hold our nose and vote for the seemingly least objectionable, with no expectations they will live up to their promises. The system is impossibly broken.

In recent years a new idea has emerged as a suggested solution to restore representative democracy to its original ideal: the citizens’ assembly. These assemblies are comprised of randomly selected members of the citizenry, with care taken to achieve reasonable demographic balance. Unelected and beholden to no one, they then, with some light-touch facilitation, self-organize to study and discuss one or more critical issues (like climate change, or election reform) in great depth, so they know enough to be able to intelligently (and indifferently) evaluate possible approaches to deal effectively with the issue. They then make recommendations which can be implemented in a number of different ways:

- The recommendations may be enacted into law and implemented, regardless of what either elected officials or the citizenry as a whole think about them. This is the approach XR has insisted is the only way that the radical changes needed to address runaway climate change and ecological collapse can be made in time to be effective. It’s basically an acknowledgement that neither elected officials nor the citizens as a whole, can be trusted to take the necessary actions or even to properly understand why these actions are needed.

- The recommendations may be forwarded to the government of the day, but are advisory only and not binding on the government. The idea is that the government will have to have a compelling reason not to accept and implement these informed, unbiased recommendations, and that if they don’t, the electorate might instead vote in a government that will implement them.

- The recommendations may be subject to a ratification or referendum by the citizens as a whole. This approach has been used to inform complex plebiscite issues and “proposition initiatives” on US ballots, where the recommendation and rationale of the assembly is included with the ballot papers and in the local press, but this is not always enough to win the vote.

Despite making sense in theory, none of these approaches has a particularly good track record. The first strikes many as being “undemocratic” and hence scary, and I am not sure I know of any case where it has actually been tried. The second has run into a “double jeopardy” problem — it’s too easy for governments to put their own short-term interests ahead of any radically new and potentially frightening policies, and for pressure groups of those disadvantaged by the changes to fear-monger against them.

And the third has usually worked only when the changes are not threatening or intimidating (or very expensive) — quite a few citizens’ assemblies’ recommendations on ballot initiatives have been approved by voters, though that might have happened even without the assemblies’ weighing in. But when the recommendation is considered to be more radical (eg introduction of proportionate representation in some areas), fear-mongering by high-paid pressure groups has almost always led to them being voted down.

Complicating matters is the issue of charters and constitutions of rights and freedoms, which are designed to prevent discrimination and oppression of individuals and minority groups at the hands of an over-zealous or hate-driven majority. Their effect generally (though usually not intentionally) is to paralyze any action in the collective interest if any group with sufficient political clout will be disadvantaged by that action. They do little to protect those who are truly oppressed and disenfranchised.

At the tribal level, it is not hard to assess and prefer the collective interest of the tribe over the personal preferences and interests of individual members. But this just doesn’t scale. When the tribe is not a cohesive group but an assemblage of thousands or millions whose only commonality is the place they call home, what exactly does the “collective interest” even mean? By contrast, the interests of individuals and groups within the larger group (be they unlicensed gun owners, protesters of various stripes, or hate-mongers on social media) are pretty easy to delineate. No surprise then that the dysfunctional courts often choose personal interests over an amorphous and undefinable “collective interest”.

And the political problems of scale go far beyond the issues of rights, freedoms, and courts’ decisions. The whole system of public security and incarceration was dysfunctional from day one. A tribe knows how to deal with those who offend the collective interest of the group — they know their names, their families, and the traumas, addictions and tribulations that generally lie behind their misbehaviours. But as soon as you scale the system up, and have to introduce criminal laws, enforcers, punishments and sentences, the whole system breaks down.

And then we have all the problems that come with the introduction, definition and regulations (and more ‘rights’) related to personal property, including the added modern wrinkle of corporate personhood and corporate rights. How is the collective interest of a community supposed to be assessed against the ‘personal’ interest of a giant corporation? If we believe, for example, as AOC’s advisor Dan Riffle puts it, that “Every billionaire is a public policy failure”, how can we possibly reform or design a political system so that it mitigates and legislates against gross inequality, without getting utterly mired in insoluble issues of rights?

We can of course dream about a system that might fix all these problems. It would be so radically different from our current system that, as they say, “you can’t get there from here”.

But there are some things we can at least practice. At the local level, intentional communities learn about consensus decision-making, with a mix of (i) delegation of most tasks to those who have the competency to do them (and are willing to take on the responsibility that comes with the authority), and (ii) collective accountability and consensus decision-making in those few areas where the interests of the collective group are best ascertained and met by listening to everyone’s thoughts, and then letting the consensus emerge. But it takes a long time, and a lot of practice, before the group learns the skill and patience to let this happen.

The same kinds of experiments and learning are happening in some progressive organizations and companies, such as those using the Teal approach to self-management. I understand that some small educational and health-care organizations are exploring similar approaches.

The larger and more unwieldy systems are likely beyond rescuing, but they are all in the process of collapse anyway, so rather than trying to fix centralized governments and large corporations and institutions, it may make more sense to wait for them to go bankrupt and get out of the way, so we can establish much-smaller-scale political and economic systems and organizations that actually work in our interest.

We all think democracy is a great idea, but perhaps it’s time to realize that it’s never worked very well, and that in a radically relocalized world democratic decision-making is really not needed that much or that often, in order for things to work just fine, in the collective interest. Like early human tribes, and wild creatures, we don’t really need any kind of “-cracy” to live and work together with decency, trust, and care for each other.

Our real challenge, perhaps, is in relearning what the “collective interest” actually means, and why it is so important, and how we got to this perverse situation where we have such monstrous distrust of each other, and of collectives in general, that we have assumed that, somehow, 7.8B people acting in their isolated individual, personal, and often trauma-influenced self-interest, will somehow be synonymous with an optimal collective interest.

It’s an absurd idea, one that could only ever be popular with reality-challenged market theorists, (“self-made”) billionaires, billionaire wannabes, and the severely alienated and traumatized.

So let me say it one more time: This is what collapse looks like. Our ability to cope with it over the coming decades will depend on our ability to work together in our collective interest, which in turn will depend on our relearning what community really means and how to build it, on our capacity to care about and trust each other, and on our willingness to let go of what was never in our collective interest — including our faith in an idea of democracy that has never actually worked as promised, and never really served us well.

Interested in how you have assembled the view of tribal decision making as it may have been in the past. Is it from reading about observations of remaining cultures now? I’ve had more of a feeling that with history, it’s only somebody’s version of a possible story based on how much sources can be trusted…

I’m not sure I think “Democracy” is a good idea in itself, I have simply been raised where it’s considered “better than dictatorship” and related to affluence and prosperity. And there’s an equation of Democracy being voting on things. Is the tribal consensus about direct voting or everyone being included in an actual conversation?

Maybe there is no collective interest at all – which is probably why I’m most attracted to anarchist thought – there’s no sense of prescribing one “system” because it’s not assumed there will be one, or it will stay the same. It seems like the issue is with the thought exercise of it even being possible to envision a system that anyone can understand that isn’t massively abstracted.

Great piece, thanks for sharing. Democracy indeed scales (very) poorly, and can be hijacked easily to serve the needs of an elite group. What keeps it afloat is the illusion of agency: a belief that we can collectively shape our future (I’ve just completed a post on that). No matter how bad it is people always hope that it could have happened another way or could be made better – while in fact our future is an emergent property of the system itself. So is its inevitable collapse – as you also pointed out.