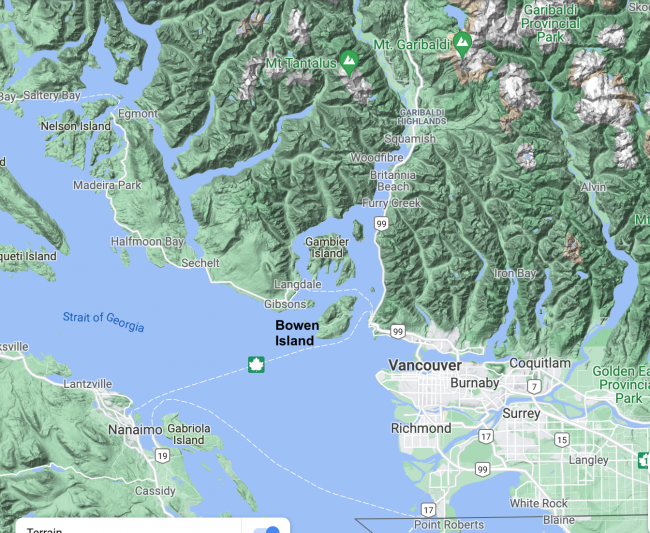

One of my small pleasures is my weather station, which is up on the roof of our apartment. (You can see the current data here.) Before we moved to Coquitlam (or kʷikʷəƛ̓əm to use its hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ First Nations name), last summer, the station was outside our house on Bowen Island (or Nex̱wlélex̱wm to use its Sḵwx̱wú7mesh name), where I tracked weather conditions and trends for my last five years there.

When you’re a weather nut, and worse, a data analysis nut, you end up learning a lot about the weather just trying to answer questions about anomalies in the data.

As a small, volcanic, mountainous island just off the west coast of the mainland of British Columbia, Bowen gets a lot of weather. It’s an entirely different world from (most of) Vancouver, of which it is ostensibly a suburb. For a start, Bowen is heavily treed. It sits in the shadow of Vancouver Island to the west, and its west side is buffeted by winds coming down the Salish Sea (aka Strait of Georgia) from the northwest, while its east side gets hammered by the notorious Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) squalls coming down the Átl’ḵa7tsem (Howe Sound) from the northeast.

Bowen’s microclimates are primarily determined by (at least) three local forces:

- The temperature-modifying effects of the surrounding Salish Sea.

- The effects of altitude, notably the cooling effects of both its three iconic mountains (that take up half the island) and its low central valley.

- The effects of winds, both maritime and offshoring.

The result of the first effect is that some coastal parts of the island get less than a tenth the winter snow of some other parts, with temperatures varying as much as 5ºC over less than one km (warmer on the coast than inland in winter, but cooler in summer).

The result of the second effect is that, while the mountaintops often get the first and most snow, the “low-lying” areas of the central valley often see more snow lasting longer on the ground than any other part of the island. The combined effect of shade both from the mountains and from the adjacent forests is a factor, but not the largest one.

This was hard for me to get my head around, and it was frustrating because the Grafton Community Gardens are located right in the middle of the island in the valley, and the snow there, some years, takes forever to melt so that planting can begin.

You probably know that as altitude increases, air pressure decreases, and as pressure drops, there are fewer air particles, and the air particles move more slowly, so temperature drops. You’ve also probably heard the expression “risk of frost in low-lying areas”. This happens because warm air rises, leaving denser, colder air below, and it can get trapped in valleys. So paradoxically, the warmest places in Bowen’s interior are the mid-altitudes — neither too high to get the effect of lower air pressure, nor so low that they allow cold dense air to be trapped there. Of course, the coastal areas are warmer still in the winter, and cooler than the valleys in the summer.

The results of the third effect (winds) are perhaps even more complicated. The winds down the Salish Sea from the northwest can sometimes bring in cold arctic blasts, but they can also bring moderating temperatures when they’re localized or coming from the south. So the south and northwest coasts of the island might actually be the warmest parts of the island, overall. The Átl’ḵa7tsem winds from the northeast get the Squamish squalls, and so the northeast coast is sometimes the windiest part of the island, and can get particularly large snow dumps in winter — though every part of the island gets a lot of wind! A study a few years ago found that the “wind regime” 50m above Mount Collins on northeast Bowen was one of the heaviest and steadiest on-land wind regimes on the entire west coast of North America.

But it gets more complicated. The prevailing winds on Bowen (and much of Vancouver) for significant parts of the year are from the east, blowing offshore. This happens naturally when the warmer ocean air rises, creating a low pressure area over the water, which the air from the land to the east rushes in to fill.

In the winter, events like the polar vortex can aggravate the situation. The polar vortex is a huge arctic low-pressure zone filled with cold air, that is semi-stable. Its winds blow in a counter-clockwise vortex, but occasionally they will be disrupted, opening the vortex and allowing the mass of cold air to flow southwards at high speeds. This can be offshore, bringing the air directly down the Salish Sea, or it can be onshore, in which case there is a large temperature anomaly near the coast. When the latter happens, as the warmer air over the water rises, the colder onshore air flows out across the coasts to fill the void. Large cold air masses trapped between the mountains ranges in winter also often produce fierce outflow winds, which is why many of Bowen’s, and Vancouver’s, fiercest storms are accompanied by winds from the east, northeast and southeast. Just a month ago, Vancouver recorded its coldest temperature in 52 years, at -15ºC.

And then, there are the “atmospheric rivers”. These are principally attributable to climate change, as atmospheric heating leads to more water vapour in the atmosphere. When this highly saturated air gets picked up by air currents, it can travel thousands of miles from the southwest Pacific, turning into heavy precipitation when it rises on encountering land masses. This happens especially in La Niña years, when the temperature gradient of the Pacific, from hot in the west to cold in the east, is greatest, fuelling this air saturation and flow. This past fall and winter, most of BC’s major highways were closed in spots for an extended period due to floods and mudslides caused by an extended series of atmospheric rivers.

And, last but not least, we have “heat domes”, also exacerbated by climate change. These also occur mainly in La Niña years, but in the summer, when the oceanic temperature gradient is high, driving record hot air up into the atmosphere in the western Pacific, where it is then carried by the jet stream to North America. This creates a problem when this air pushes into a high pressure area with clear skies. The high pressure is seeking to move to a lower-pressure (cooler) area, but with the flow of hot air from the Pacific, it can’t find one. As it presses down on the air below, that air is compressed and further heated. The hot air at ground level is trying to rise, but is blocked by the high pressure heat above, creating a dome that can take days to finally break. This past June 29th, a month before mid-summer, Lytton BC, not far from here, reached almost 50ºC, the day before the entire town was engulfed and burned to the ground in a wildfire. That temperature was 6ºC higher than the previous record for any date in all of Canada, and 27ºC higher than normal; most of the province likewise surpassed previous records. Squamish hit 43ºC, and Bowen and Coquitlam and other parts of Vancouver hit 41ºC (normal high temperature for June 29th in these places is 18ºC).

These temperatures and weather anomalies also contributed to a horrific 2021 wildfire season (third worst on record), and record droughts, especially on Vancouver Island, where many wells ran dry and water rationing was widespread.

That is what climate change’s promise of “more extreme weather events” means here. Heat domes with record hot, dry summers. Increasing droughts and wildfires. Winters with record rainfall, widespread mudslides and flooding, and, at higher altitudes, record snowfall and avalanche danger. Unprecedented and sustained windstorms causing major damage. Increasing polar vortex and other outflow anomalies, leading to long periods of abnormally cold temperatures, and the ravages of ice storms. (February has recently replaced December as Vancouver’s coldest month, four years out of the last five.)

It all “averages out” to a 2ºC overall increase in temperature, and a slight overall increase in precipitation. But in no place and at no time is anything “average”. Not all years will be as extreme, weather-wise, as 2021, but some will be worse. And some places will fare much better than others, even places that are not far apart.

Our move from Bowen to Coquitlam (see map above) wasn’t that far, but I am definitely living in a very different world. Some Bowen friends were snowed in for a week this winter, despite their years of preparation and practice at dealing with the vagaries of the local weather — the first time in over 20 years that’s happened to them. Others had to drink bottled water when their wells ran dry. Some of their roads were washed out in this winter’s floods. Most of them faced the 41ºC heat without air conditioners. And this fall and winter storms have caused a slew of power outages, perilous when it’s -10ºC and you rely on electricity for your heat. The potential dangers of wildfires are ever-present.

By contrast, living in the city one can be pretty oblivious to what’s going on all around. Coquitlam is one of those ‘mid-altitude’ areas that is, unexpectedly, slightly warmer, on average, than downtown Vancouver and quite a bit warmer than Bowen. We faced the heat dome and have had lots of rain, but have had little snow, no major power outages, no floods or mudslides or avalanche closures or nearby wildfires. No worries about dry wells or downed trees across the roads or wrecking roofs. The air quality was bad province-wide due to wildfires last summer, but here they were not as bad as they were three years ago. Perhaps, so far, we’ve just been lucky.

And that’s your weather report for southwestern BC. Stay tuned for updates, and hold on to your hats.

I always thought that talking about the weather might be an easy “ice breaker” in an unfamiliar group, but these days it might be triggering. Facilitators be warned!