my synopsis of the some of the elements that might comprise one’s Ikigai; any misunderstandings about ikigai here are mine

my synopsis of the some of the elements that might comprise one’s Ikigai; any misunderstandings about ikigai here are mine

For those unfamiliar with the ancient Japanese concept and philosophy of ikigai, it is about the lifelong discovery, appreciation and acceptance of who you really are, now, authentically, as gauged by what gives you joy, what you care about, and what is in your true nature.

(Contrary to some business consultants’ perverse and simplistic misappropriation of the concept, ikigai has absolutely nothing to do with “the work you’re meant to do”, or “finding your purpose”, or in fact about anything aspirational.)

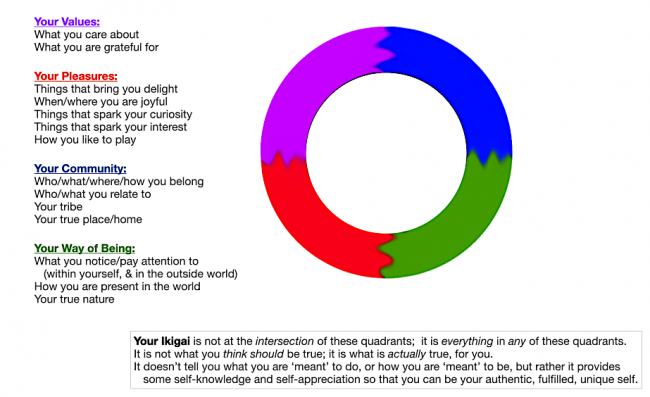

The diagram above is my attempt to capture the various aspects of ikigai. It is different, and evolving, for each of us. Mine, for example, currently encompasses the following:

- listening to my favourite music (these days, mostly ‘world’ music), and discovering new music

- indulging in hedonistic pleasures (eg hot baths by candlelight; Ayurvedic massage)

- just being in a state of equanimity, curiosity, and discovery, anywhere (eg at the local café or lake, enjoying the view from my apartment, or on warm ocean beaches and in tropical rainforests and elsewhere in the natural world)

- watching/listening to clever humour and theatre

- non-competitive play (eg board games, flirtations, clever exchanges, challenging puzzles, pick-up sports where no one keeps score, and collaborative creative activities)

- exploring new ideas, discoveries and learnings with gentle, joyful, exceptionally bright/perceptive people, close friends, and my ‘blog community’

- reading and writing in order to learn new things — these days particularly about (our lack of) free will, the (illusory) self, and what has been called ‘radical non-duality‘

- writing short stories, poetry, music, and other creative works

I am immensely fortunate and grateful to have been able to retire from paid work while still in good health, so I get to spend a fair bit of each day doing these things. I’ve never been particularly ambitious or industrious, so doing these things isn’t about accomplishment or creating a ‘legacy’; it’s just about maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain.

So why should we try to ascertain what our personal ikigai is? Why should we care? I think of it as kind of like a compass: While I don’t believe we have free will or control over what ‘we’ do, I find it comforting to have achieved (just) enough self-awareness to appreciate what my conditioning has predisposed ‘me’ to do, and not to do. So when this body, and its brain, does its thing, ‘I’ am less likely to be (unpleasantly) surprised. I can kind of laugh at this strange creature whose body I presume to inhabit, as it does whatever its conditioning has compelled it to do, even when ‘I’ am rather chagrined by its actions.

I acknowledge that ‘I’ (my self) am really just a witness and observer trying (usually foolishly and pointlessly) to make sense of everything, and ‘I’ (caught up as I am in the closed loop of ‘me’) can never hope to know or understand what is really happening.

But if life is just a show that we’re watching, helplessly, from the stands, somehow it helps to have a rough ‘theatre program’ to provide a bit of perspective about the performance we’re witnessing. And that’s what I get from identifying and tracking my ikigai.

My ikigai is not aspirational — it’s not about hopes and dreams and ‘shoulds’. It’s just an honest list of what (voluntarily) gets me up in the morning — what pleasures I find and enjoy in life, right here and now, and by implications what pains I am avoiding by not doing other things. Even if I can never know where I’m going or why I’m doing what I’m doing (our conditioning is more complex than we can ever know), it’s useful, I think, when I find ‘myself’ doing something, do be able to say “Aha, this thing I’m doing is (or isn’t) on my ikigai list. This is where I am, now, on this ‘map’ of ‘what the character called Dave does’ “. There’s a certain contentment that comes, I think, with this degree of apparent self-awareness.

At one point recently, I found myself (unusually) unhappy, and couldn’t put my finger on it. Part of it was some uncontrollable stress (which generally triggers me), but I realized that another part of it was not spending my usual amount of time doing things on my ikigai list. I actually have a colour code on my calendar to denote fun, ‘ikigai’ activities, and that colour was decidedly absent from my March and early April calendars. It didn’t change anything about what I was doing (that’s all the result of my conditioning), but it did make me self-aware that I was not doing many of the things that usually bring me joy. And somehow, that self-awareness seems to make a difference.

Self-awareness is kind of paradoxical, especially when, like me, you acknowledge your self as illusory, as a phantom, a mere mental construct. But, to use a very imperfect metaphor, I suppose if you’re going to be haunted by a ghost, it probably helps to at least know where it is and what it’s doing. The paradox is that you’re only going to become (more) self-aware if your conditioning enables and compels you to do so. That’s how the closed loop of ‘me’ works. For most, I suspect, there will just be the haunting.

I do like the idea of conceiving of the self as a witness, an observer, rather than as just a disease of our bewildered and entangled human brains. But it’s still mind-boggling to contemplate that that witness, that observer, is not only illusory, completely helpless, and in control of absolutely nothing, but that its existence is completely unnecessary to the healthy functionality of this rather funny-looking creature it has always presumed to inhabit.

Having a list of my ikigai has also provided me with some insights about some of the things ‘I’ can’t control: My desires, my fears and phobias, my addictions, my aversion to stress and conflict, and my seeming misanthropy. Radical non-duality speaker Tony Parsons, describing people’s use of religion, spirituality, therapy, meditation, power, money and other means to cope with the trauma, suffering, sense of emptiness, and/or unhappiness in their lives, says this is perfectly understandable, because these things can “make the prison of the self more comfortable — at least for a while”. Perhaps that is how this self, at least, employs its ikigai. Spending as much of my life doing these things as possible has made me a very happy person, most of the time.

One of the things that self-awareness has brought me is an understanding of my apparent lack of need for a lot of social activity. My ikigai list above is, after all, mostly solitary pursuits. Some people have described this lack of social contact, especially the absence of intense, personal relationships in my life, as unhealthy and perhaps dissociative. I have no idea. I don’t feel like I’m missing anything. I used to fall in love way too easily, and that no longer happens (not recently anyway). I like people’s company, and avoid situations where I’m isolated, but feel no great need for conversation or emotional connection. That seemingly would never work for most people I know, but it seems to work fine for me.

And my ikigai list also has no ‘bucket list’ of extraordinary adventures, or even travel to interesting places, or parties, or celebrations. I love being in warm tropical places — they just feel like ‘home’ to this body — but the stress of travel to get there and get organized keeps them off my list. As a result it’s an unambitious list, and one that I’m sure a lot of people would find boring. Not me.

While I still employ my blog for its longstanding purpose of “chronicling civilization’s collapse”, I no longer find that kind of research and writing enjoyable, if I ever really did. So it’s not on my ikigai list. I always had a passion for knowing things, for being ahead of the crowd in understanding how the world works. Somewhere that passion died. It gives me no pleasure to know that I was writing about economic and ecological collapse 20 years ago when such writing was mostly considered crazy, and now it’s quite mainstream. I’ve never felt it important to be ‘right’. I study things just because I enjoy learning. During my long bouts of depression in my younger years, learning new things was my primary coping mechanism.

During my work life, my customers brought to my attention that my unique gift, the thing I brought to work assignments that those customers most valued, was my capacity to ‘imagine possibilities’ — ideas, inventions, applications of some activity (often from nature, biomimicry) that might be used in an entirely different way in some entirely different activity. I suspect that arose partly because I have always been fascinated with broad rather than deep learning, so I read up on a lot of very different subjects, and, as a somewhat solitary child, my imagination got an exceptional workout. I still think I am quite competent at doing this, and I apply it in some of my volunteer work, and indirectly at least in some of the activities on my ikigai list. But for some reason it’s not nearly as important as it once was. My recent conditioning has prompted me to try to pay attention more, and perhaps that requires to me imagine less. But competence really is all about practice — I’m still lousy at paying attention, and still good at imagining possibilities no one else seems able to come up with.

I also wonder what happens when, as Robert Sapolsky has explained, some of our naturally, biologically conditioned preferences cross the line into what can be called addictions — we need more and more, sometimes to an unhealthy degree, to get the same pleasure from them. Some of the things on my ikigai list might just be addictions. It’s an issue that clearly concerns Robert, and I share his concern.

All of which is to say, in my usual long-winded and tangent-prone way, that I have found compiling, updating and referring to my ikigai list a fascinating and self-illuminating process.

What intrigues me is that, when I talk to people about their joys and ‘passions’, most people admit that they’ve never really thought about it. In some cases, they will assert that they think such an exercise would be just a waste of time (for various reasons). But more often, to my surprise, I discover that they wouldn’t even know where to begin to identify them. Even when I’ve given them some of the prompts in the graphic at the top of this post, it is clear they’ve never thought about the subject. Nothing wrong with that of course — it’s just so different from how I am.

I’ve read about other people’s ikigai lists (usually shorter than mine) and find them almost as interesting as maintaining my own. Should you have your own list, and would be open to sharing it by email or zoom, I’d love to hear it and will keep it confidential. Not curious why anything is on anyone’s list, but rather just the fact that it is.

These days, when I meet new people, I no longer ask them what they do for a living, or about their family life, but instead gently try to discover what they really care about. Asking them about their ikigai might just be a graceful way to start that conversation.

It makes a lot of sense, Dave, what you say. I enjoy your self-reflection and always learn something from it.

As for the non-existing self… I challenge you to re-write this article without once referring to your self, in such a way that you convey in a non-self mode what you said here in a selfing mode. Can it be done?

No, I don’t think it can be done. Abstract language was developed to codify, explain and hence reinforce our sense of self and separation. We cannot use it to describe the non-existence of self and separation.

Radical non-duality speakers use the terms ‘I’, sometimes somewhat apologetically, and avoid using “apparent” and “apparently” as every second word they say, because otherwise the message gets so convoluted it becomes indecipherable. It really is impossible to convey in words.

Those listening to the message, I think, are a mix of (a) people who have an intuitive and/or intellectual appreciation of the message, perhaps due to ‘glimpses’ when it was undeniable, and (b) people who really really want to believe the message, and will twist it every which way to mean whatever they want it to mean, which is mostly nothing to do with the message at all.

Another practical and wonderful post Dave – thanks so much. I know you had touched on this topic before, but great to have an update. It’s funny but I have been thinking so much lately about the desire for pleasure and feeling good in the body. How this seems to be such a strong motivator for me, but also how it manifests very differently for other people, and when does pleasure merge to addiction. I can also relate to what you say about being a solitary creature. This is something else that i have noticed after a few years of being in lots of different groups to do with anticipating /accepting collapse, and realise that gradually I have gravitated back to mostly just being on my own, being in nature as you say, and being only with my family as the little community. And I figure that if this pattern is like an equilibrium that I return to again and again, regardless of my thoughts or ideas about what is healthy, then it is what is, my nature or ikigai. I have maintained just one close collapse buddy, and we connect weekly and at the start of the year we thought that together with might have goals mapped for the year ahead, but we never quite got there. I think instead this ikigai map is a much better way to approach it – and I get it, totally NOT aspirational, just a reflection on where the joy lies in your life, and when it’s absent, looking at the list for some more self awareness. Anyway I will take some time to consider these four points of the compass (and see if my friend wants to do so too), and I will send your way at some stage. It would be great to do some kind of anaylsis if you get a good response ;-)

Thanks Renaee. Yeah, I like that ikigai is very positive — not about what you ‘should’ do differently or better, but what gives you joy right now. Ken Mogi in his book talks about “what gets you excited about getting out of bed in the morning” (in a positive way, and beyond the first shot of caffeine), and I think that’s a good way of thinking about it.

I feel sad that there are so many people I know for whom their first and greatest joy is checking things off their ‘to do’ lists.