This is #29 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk, hike, and explore in my local community.

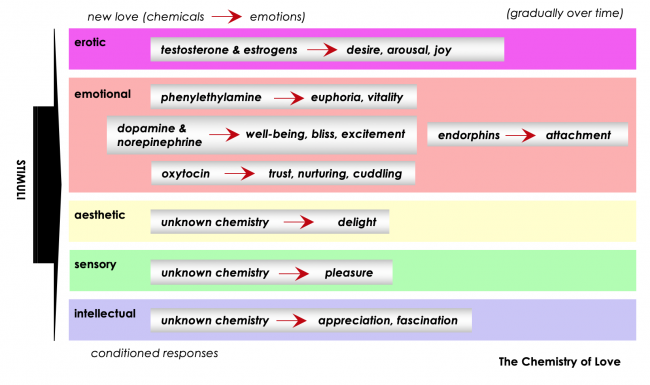

Chart above is my own invention, having studied the various chemicals that scientists believe are involved in feelings of intense love.

The title of this post is a quote attributed to Jimi Hendrix, when he was asked in an interview to explain the special chemistry he had with his audiences.

It’s impossible not to look at them. They are possessed, so utterly consumed by the flood of chemicals feeding off each other that they are oblivious to everyone else in the café. Their feral passion for each other is at once riveting and disconcerting. A man noticing their antics looks disapprovingly. A woman looks at them with a torn expression, a mixture of what might be dismay and (perhaps nostalgic) envy…

… But I’m getting way ahead of myself. Back to this couple in a moment.

This body has taken me for a walk, today, to the nearby lake. It’s a rare sunny spring day here on the temperate rainforest coast, and there are lots of people about.

Recently I’ve been reading a lot about bonobos and chimps, our cousins from which we separated evolutionarily about six million years ago, and with whom we still share almost 99% of our DNA. As Robert Sapolsky discovered with his suddenly-matriarchal and peaceful baboon troupe, the rather extraordinary differences in behaviour between chimps and bonobos in the wild (most people can’t tell them apart) are not biologically, but culturally conditioned. Chimps and gorillas evolved on the north side of the Congo river; bonobos on the south side. The river was too wide for the species to cross. The chimps, having to compete with gorillas and other species for food and resources, evolved high-stress scarcity behaviours — notably rigid, often violent, xenophobic, highly-competitive patriarchies, where murder and infanticide are common.

Bonobos, blessed to have no significant competition for their food and resources for millions of years, evolved and continue to exhibit low-stress abundance behaviours — matriarchies* based on trust and sharing, welcoming strangers, and discharging any brief stresses through ubiquitous and frequent sexual and grooming activity, in healthy social communities where murder and infanticide have never been observed.

Our species, it seems, was raised on the wrong side of the evolutionary river, and so most of our behaviours would seem to resemble far more the behaviours of chimps than of bonobos. But what is endlessly fascinating to me, as I now watch the small groups of seemingly-biophilial hominin creatures we call ‘humans’ playing beside, and wandering around, the lake, is the idea that the entire difference between our three species is accounted for by cultural conditioning in the context of very different (scarcity vs abundance) environments. Were it not for differences in those environments, and the cultural conditioning we have subjected each other to as a result of adapting to those environments, we, the humans, the bonobos, and the chimps, would likely be indistinguishable.

Chimps are, in fact, more or less just bonobos acculturated to living with scarcity. And humans are really just hairless bonobos likewise acculturated to living with scarcity. The physical differences in appearance (including our brain structures and body chemistry) are evolutionary adaptations to our environments and the stresses that those environments produce. In essence, in the grand scheme of things, we are the same creature.

So as I sit on the bench by the lake smiling and nodding at these strangely-attired fellow hominim creatures, I cannot help now but see them, and myself, as just hairless bonobos who got an evolutionary bad break in our early history, in the geographies of stress and scarcity where we emerged, and have adapted our behaviours accordingly, aggressively, tragically, the only way we possibly could have.

We are, underneath the trappings of civilization culture and its adaptations and adornments, wild creatures. Thanks to a process we call self-domestication, we have conditioned each other to create our own prisons (with unlocked doors that we voluntarily return to each day after ‘work’), and our own CAFOs — “concentrated animal feeding operations” (though we call the ones for humans ‘cities’) — to confine ourselves in. We have done this with the best of intentions, and perhaps prevented the mass murder and mayhem that would inevitably result if eight billion of us were not so strictly repressed and conditioned. Everything is falling apart, but damn we were able to hold it all together, incongruously and astonishingly, for a remarkably long time.

Or, rather, ‘we’ didn’t hold it all together. It is our evolving conditioning, directed by ‘our’ body chemistry, that has produced the terrible wonder of our civilization. Just trillions of chemical responses to sensations and stresses compelling the complicity of creatures that comprise each of what we call ‘our bodies’ to do what they do. Kind of amazing when you think of it. But then, nature has had billions of years to get this process working the way it does.

Yesterday, in the café, I witnessed the behaviour of two creatures of our species briefly released from the constraints of civilization culture’s conditioning. As described at the top of this post, these two bodies, which I am guessing had been around in their current form for about twenty years, were engaged in a primitive, ancient, mating dance. As they looked at each other, you could almost see the continuous oxytocin loop that they were reinforcing, and conditioning, in each other. Although they were speaking English (not that common an occurrence in my neighbourhood café), the words they were saying really didn’t matter. It was the extraordinary tone of their communication — high-pitched, breath-y, almost gurgling — that was important, doing the work of drawing each other in.

I was immediately reminded of my own behaviours in past moments of falling in love with someone new. The powerful cocktail of self-generated chemicals, shown in the diagram above, basically blew away my inhibitions, my fears, and my entire sense of self. It was only afterwards, in the hours or days after I first fell hopelessly in love, when my ‘self’ rushed back in, and all the feelings of anxiety and jealousy and doubt and shame arose. I would submit, now, that these ‘negative’ emotions are uniquely human, a consequence of the terrifying sense of having a separate self that must look after itself and look after others and be responsible and be ‘in control’. Kind of spoils the whole moment in a hurry! This is, I think, what happens in the transition from ‘falling in love’ with someone to simply loving that person. A very different set of chemicals is involved.

Speakers about radical non-duality assert that this ache for the ‘love of another person’ is actually a need, a desire to fill a sense of incompleteness and emptiness that arises when the separate self is first conceived. Without the sense of a separate self (and there is some evidence that even bonobos and chimps lack this sense, and are none the worse for lacking it) I suspect that none of the anxiety and jealousy** and doubt and shame that so often fall quickly on the heels of the mind-blowing positive feeling of ‘falling in love’, could arise. Falling in love requires no thinking at all; loving someone anxiously or jealously, I would argue, entails unhealthy overthinking, a ‘scarcity’ behaviour that is based on conditioned beliefs that there is never enough love and caring to go around.

Of course, the intensity of falling in love diminishes over time, as nature and evolution ensure that the prospective new parents cease being helplessly moony and start preparing to look after the offspring. Nature does this by changing the mix of chemicals the couple’s mutual presence provokes (shown on the right side of the diagram above).

As I (as discreetly as possible) watched, and tried not to watch, the young couple in love, I realized, somewhat uncomfortably, that the young woman’s body language, eye gestures, and voice tone were affecting me. This was not just me feeling guilty for being voyeuristic. I could actually sense changes in my own body chemistry. I could rationalize all I wanted that her attentions were not directed at me, and that any ‘response’ from me was completely inappropriate, if not absurd and a little creepy. But my body was doing its thing — I was just along, helplessly, for the ride.

And then another thought occurred to me: The young man‘s body language, eye gestures, and voice tone were also affecting me. This of course made no ‘sense’ to me. Yet my body’s reactions to his actions were just as positive as its reactions to the woman’s. I would bet that if someone were to have taken a blood sample right at that moment, it would have shown elevated levels of several of the chemicals in the chart above. Like it or not, ‘we’ are constantly and continuously conditioning each other.

I looked around at the man and the woman who had clearly noticed the young couple’s behaviour. They were both looking away. I wondered what a test of the chemicals in their blood at that moment might have revealed.

We’re just hairless bonobos, all of us, conditioned to be, and at the same time conditioned to deny and suppress, what we are, I thought as I bussed my table and, laughing at myself, left the café. “It’s all chemistry, isn’t it?”

…..

The behaviour of the humans in the park today seems much more bonobo-like than chimp-like to me, and I wonder whether, despite living in a world of stress and scarcity, and being afflicted with the dis-ease of a sense of self and separation, we aren’t nevertheless a lot more like the bonobos than one might imagine.

I watch as a mother talks with her baby as she sits on the bench looking at the ducks. The same oxytocin loop is evident in their eye-contact and their ‘gurglings’ that I observed with the couple in the café. The mere tone of her chattering to the baby, I suddenly realize, is calming me, though I’m standing too far away to either hear the words or be infected by whatever chemicals her body is giving off.

A few minutes later I watch a couple stoop down to pet an adorable looking little dog. I’m looking at the canis-hominin eye-contact, and, sure enough, there is seemingly a lot of it, though the woman is more focused in her attention. Recent research suggests that dogs and human women also exhibit oxytocin-loop chemical changes when they interact, while with men, there are no such changes. The same research suggests that domesticated dogs evolved to retain and enhance puppy-like juvenile physical features and behaviours throughout their lives (including more white sclera, that I mentioned in last month’s meandering post), possibly to ingratiate themselves into human societies.

This was the dogs’ own evolutionary self-adaptation, and not the result of selective breeding: A long-term study was able to reproduce this evolutionary change in wild foxes over many generations — wild foxes that were shown a lot of human affection in puppyhood actually evolved and retained more puppy-like physical features than a ‘control’ group of wild foxes raised in exactly the same circumstances (a fur farm) but without affectionate handling by humans. Who’s domesticating whom here?

As I make my way around the lake, I slow to watch two older women sitting on one of the lakeside benches. Again, I notice some concentrated eye-contact between them. They might be related, by birth or by marriage (including marriage to each other). What I notice between them, however, is something intangible, something that resonated with the videos I watched of bonobo females (though I confess this is entirely conjecture and might be completely wrong): I detect a sense of unconditional trust between them. Perhaps this stands out because I so rarely see that, even from married couples I know. I wonder if our high-stress, chronic-scarcity civilization culture has conditioned us to trust no one unconditionally, even those we presume to love.

I remember the look on the young woman’s face in the café the day before, rapt in the chemistry of love. It’s not that she trusted the young man she had fallen for; it’s that, thanks perhaps to the chemical cocktail she was drowning in, she had a brief respite from having to trust or to distrust — perhaps, just as in wild creatures, there was a precious moment when she ‘was not her self’, so there was only the feeling, and no ‘one’ ‘there’ to have the feeling. I hope so. A world where no one can be trusted unconditionally must be particularly stressful, even terrifying, for most women. I wish it were otherwise.

So what’s going on with all these encounters? Just trillions of tiny creatures — cells, molecules, organs and tissues — each doing their own infinitesimally small, infinitesimally important thing, chemically interacting with all the other creatures, appearing to be a collective, integral, entity (a ‘body’ with a ‘self’), but actually not — none of the tiny creatures is ‘in control’ of the entity — human, bonobo, dog, or duck. Their concerted and complicit efforts produce what only appears to be a centrally-controlled, rationalizable action by the entire entity. In reality, there is no entity.

It’s all just chemistry.

* People often ask primatologists how the bonobos could evolve into a matriarchy. The answer, it seems, comes down to the fact that, absent unwanted sexual violence, it is the bonobo females who choose who they breed with, and their choice is usually strong but gentle males. So over time, aggressiveness in bonobo males was selected out of the gene pool. Still, aggressiveness in adolescent bonobo males is common, but it is quickly (and sometimes violently) ‘put down’ by groups of adult bonobo females; culturally conditioned, the young males quickly learn to behave, and to defer to the matriarchy. There are some remaining unanswered questions though: Why do adult bonobo females, unusually, have higher testosterone levels than males? And why, despite the astonishing frequency of sexual activity among them, do bonobos have rates of reproduction just sufficient to keep their numbers steady and in balance with the rest of life in their ecosystems?

** While of course any animal can be conditioned to feel fear and rage, and can be traumatized, I’m ambivalent about whether animals other than humans feel emotions like jealousy that necessarily entail judgements about ‘oneself’ vis-à-vis another ‘individual’. It’s possible that when bonobos and dogs appear to resent affection shown to another of their species, this is just an instinctive reaction to a perceived scarcity of something valuable. There is some evidence that non-human animals do not have (or need) the concept of themselves or ‘others’ as separate ‘individuals’. So while they may well fight over a scarce resource, they don’t ‘hate’ or feel ‘jealous’ the way we do, where that negative feeling is directed at some ‘other’ who is judged to have, perhaps ‘deliberately’, threatened us in some way. In fact, bonobos are polyamorous and exceedingly generous, instinctively sharing what they have, even with ‘strangers’, in situations of abundance. The link between the emergence of a sense of self and separation, and environments of chronic stress and scarcity, is certainly a complex one.

This was a rich and intriguing read! – what a day you had at the cafe then the lake. I’m really glad you shared all this and did not skimp on the details. How different life could be if we had an appreciation of all this going on at a younger age, to have this kind of awareness and insight from the get go, instead of being so convinced or sold on the idea of me and my self determination. I guess that unknown chemical for intellectual appreciation/fascination is part of your motivation to write these essays as I know it is for me to read them (will go on my ikigai list), there is some kind of alteration or lighting up of the brain in this making sense or getting it feeling? Good that you included that last asterix of info on the bonobos and those last two questions are like a chicken and the egg scenario. So it’s not the testosterone that produces the behaviour, but the behaviour can bring about the testosterone in them maybe? But unknown re the reproduction rate. The book by Vanessa Woods will be on the reading list too – thanks as always.