photo from wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0

It seems to take me a while to really process things I have come to understand. There’s the initial “aha!”, and then there’s a kind of backsliding or forgetting, as I try to reconcile and integrate the new understanding into my very complicated, unwieldy, and tentative worldview. I’m not sure what that’s about, but that appears to be how this mind, this self works.

(Even now as I write these words I’m thinking: “That can’t be right; there is no mind, no self, so how can there be some understanding of how it works?” I have no idea; that’s still in the process of being worked out, and ‘I’ am clearly not in control of the process. My conditioning is messy. This whole paragraph can’t possibly make sense. Never mind.)

When I retired, I revamped the categories I used for my posts, streamlining them to just six: Creative Works, Collapse Watch, How the World Really Works, Our Culture/Ourselves, Using Weblogs & Technology, and Working Smarter. The latter two, which used to be the subject of most of my writing, have hardly been used since. Hard-coded blogs went out of style, and I lost both my edge and my interest in writing about technology and the work world.

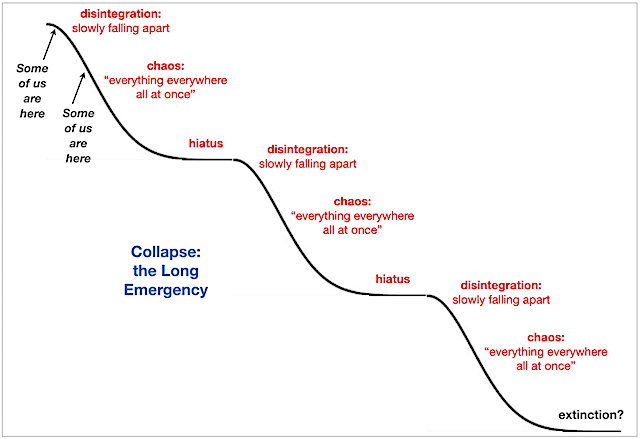

At the same time, I reworded my ‘masthead’ to more accurately reflect what I was writing about: A “chronicle of civilization’s collapse, creative works and essays on our culture”. Very slowly, the tone of my posts became less prescriptive, as I realized how little I actually know, and that almost all of what I think I know is really just opinion, and provisional at that. That’s not new-found humility — I’ve come to realize that almost all of what everyone thinks they know is just opinion, and for the most part it’s arrogant and muddleheaded.

Accordingly, most of my writing (I still backslide regularly) shifted from the second person conditional or first person plural imperative (“you/we all should/need to/might be best to…”) to first person singular (as in this post: “here’s what I think I’m seeing/learning”). Likewise my “what we should do” lists about collapse have morphed into “reminders to myself” lists about accepting and adapting to collapse. Qualified words and phrases like “seemingly” and “apparently” and “my sense is that”, now seem (see what I mean?) to have taken over much of the space in this blog that previously conveyed urgency, necessity, absolute conviction, and outrage.

So this blog has slowly become less a “what to do” blog and more of an actual chronicle, capturing as best as I can sort out what is actually happening, and why it is happening, and not prescribing solutions, as collapse is a predicament that has outcomes, not a problem that has solutions. My reading choices changed commensurately — I have pretty much stopped reading anything that proffers prescriptions on what “should” be done, or which is clearly just opinions and rehashed propaganda disguised as “factual information”.

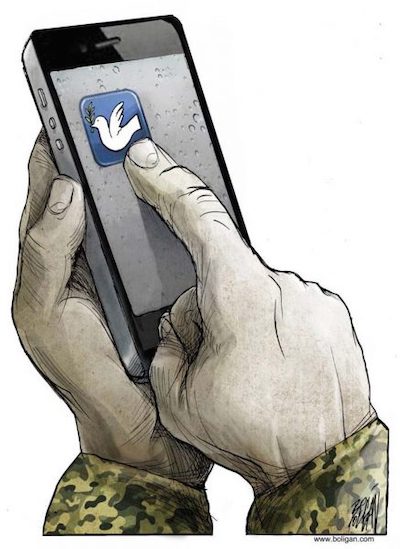

I am still reading just as much, but it is a vastly different set of readings. I no longer read any mainstream news at all, other than local news stories. Some of the blogs and newsletters I do read provide a quick digest and dissection of the mainstream media’s BS of the day, so I’m still aware of what misinformation most people are still subjecting themselves to. Much of what I’m reading is analyses of what is actually happening in the world (not what propagandists would have you believe is happening) that has been written by historians, economists, insiders, whistle-blowers, and deep thinkers who provide background and context for what is happening, and can help me see why things are happening the way they are.

That why never has anything to do with good vs evil, insane people, secret cabals of people who “actually control everything”, or the usual range of absurd conspiracy theories. Real life is not a Hollywood movie. My newer, more sober reading has finally made me realize that we are all doing our best (what we think is the best thing we can do both for ourselves and those we care about, even if that ‘best’ is awful), and then (and this was even harder to accept) that there is no such thing as free will and that we are all just acting out our biological and cultural conditioning given the circumstances of the moment, so no one is in control of what is happening.

When I first realized this, I felt compelled to create another blog post category for my writing, a category called Illusion of the Separate Self and Free Will, which explored both this new understanding of human nature and the human predicament, and the even more radical idea that there is no self to have free will, that the self is an illusion created by the brain to make sense of its model of reality.

For a while there was this kind of schizophrenic shifting happening in my writing, between the perspectives of the angry activist Dave, the resigned collapsnik Dave, and the equanimous nonduality Dave.

But more recently those three perspectives have all started to blur together, and it’s getting harder and harder to tick off any one category box when I index my new blog posts. It’s all connected. And I have no choice or control whether to be angry, or resigned, or equanimous about what I am writing, though I’m beginning to appreciate why, at different times, I feel all three reactions.

Still, I think I owe it to (most of my) readers not to annoy them with articles about our apparent lack of free will, let alone our lack of real selves, when they presumably come here to get interesting/alternative insights about collapse, about our culture and human nature, or about what is actually happening in the world, and why it is apparently happening.

But I’m increasingly sensing that this ‘compartmentalization’ is bit dishonest, and probably confusing, since the entire lens through which I now view my chronicle of collapse is one in which we have no free will.

(And worse — it’s one in which there are no selves and no separation, just things apparently happening, outside of space and time, to no one, for no reason or purpose, and in which nothing really matters. Gah! Even I am not ready to completely embrace that lens. How could I possibly inflict it on my readers? Or am I just self-concerned that my readers will all quickly unsubscribe and turn to reading saner stuff? Never mind — let’s just leave it at ‘no free will’.)

But this blurring of the categories of this blog seems inexorable. It’s impossible to write about our culture or human nature without taking a stance on whether we do or do not have free will. It’s impossible to write about How the World Really Works without the presumption that the very nature of reality either is, or isn’t, what most humans believe it to be. And it’s impossible to write about collapse without being clear that the lens I see it through either does (sometimes) or does not (at other times) presume the existence of free will, time, and real, separate human selves.

I can’t have it both ways. The more I (slowly, slowly) integrate my emerging views on free will and on self and separation, into my writing on our culture and collapse, the more I’m likely to alienate readers who don’t share that perspective, even if they try to get their head around it, and even if they agree with and appreciate the insights and information my writing tries to provide.

I blame the fact that I’m a slow learner for this disagreeable situation. It took me forever to really understand, formulate and articulate Pollard’s Laws, even though they were intuitively obvious to me long before I did so. It seems to be taking even longer for me to integrate the worldviews behind the angry Dave, the resigned Dave, and the equanimous Dave. I’m not sure I’ll ever resolve their differences, and I’m even less sure that most readers of this blog would be happy if I did. The angry Dave is too self-righteous, and the resigned Dave is too dark and bleak, to abide for long. And the equanimous Dave is just unfathomable.

I keep reminding myself that life is apparently a successive approximation process. We absorb, we process, we accept or reject, we hypothesize, and we adapt our worldview, and our actions, accordingly.

Or more precisely, our genes, our bodies, our culture (the people we pay attention to), and the circumstances of the moment combine to condition us to do so. We are a perpetual work in process, in more ways than one.

But only apparently. Maybe. That’s the script that appears to be playing out. It would seem to be a grim story, an epic tragedy with probably an awful ending. But it’s only a story. Perhaps.

If I ever figure it out, you’ll be the first to know. Hopefully long before I do.