This is a partial, edited transcript of a meeting held by Tim Cliss in 2021, on zoom. Probably not of interest unless you are intrigued by the message of radical non-duality. At the end of the transcript, I ponder a bit on the subject of human trauma.

“The Dissolution of the Self” by Midjourney AI; my prompt, photoshopped

Tim’s introductory remarks:

We’re talking about life, being alive, aliveness. Whatever we want to call ‘this’, it’s not in parts, Parts are an illusion, and the central illusion is that “I am apart” (from everything) or “I am a part” of something larger. ‘Life’ is whole and complete. There is no ‘oneness’ to be found or become ‘one’ with. There is nothing ‘apart’ or ‘becoming’ anything. This is the end of the possibility of becoming. Everything is exactly as it is ‘already’ in every way. The sense of self is a sense of being apart, excluded, separate.

There isn’t anything ‘in place’ of ‘me’. When ‘I’ am no more, there is nothing instead, or better. There is no ‘you’ to be replaced, so the seeming absence of ‘you’ isn’t even noticeable, because ‘you’ already are not what you feel and believe your self to be, which is apart.

The (terrible) term ‘non-duality’ is just pointing to the illusion, the mistake, the misunderstanding, that ‘you are’. The problem with ‘I am’ is that that felt sense of being separate, ‘inside’, with everything else ‘outside’ is so convincing it seems impossible that it can’t be true. The conviction that ‘I know who I am’ becomes so powerful that it becomes the centre or lens through which all other happenings and experiences are filtered ‘in relation to me’.

Because ‘I’ have this felt sense of being absolutely real, I believe my story is real, and in that is most of what we call suffering. “I am real and I did something yesterday and I could have chosen to do otherwise or differently. And because I will exist tomorrow I need to work on ensuring that I do better tomorrow, and that I keep myself and those I care about safe now and tomorrow.” These misunderstandings arise as anxieties and neuroses and insecurities.

It can happen seemingly that this illusory sense of ‘I am’ can dissolve, or fall away. It isn’t ‘seen through’, or ‘realized’. It just no longer appears. That can be slow and excruciating or instantaneous. That’s the whole message: Self isn’t real. ‘This’ is not something that can be known or seen or been.

There is a longing not to feel that sense of separation. But ‘this’ is not at all what the self wants or imagines. The ‘me’ wants to know, and in the absence of ‘me’ nothing can be known, or learned, or obtained, or achieved, or lost. And the equality of everything can then feel like love, but not a love for someone, or a love that has conditions. It is a love that simply, unconditionally, is.

…..

[after the above introduction, Tim answered questions from the meeting’s attendees; in the edited transcription below, I have abridged many of his answers, and grouped answers to related questions by topic, even when they occurred at different times in the meeting]

Money and Power:

Separation feels very unsafe; this tiny me in this vast universe. Money and power are sought by some because they give the illusion of greater security. But it’s just an illusion. And with more money and power come more choices and responsibility, more to lose and hence more suffering. But nothing is separate. There is no one to have anything. But absolute poverty and powerlessness is unthinkable to ‘me’. Yet there is only ‘this’ and it can’t be found or achieved or lost. There is no ‘you’ to have things, and no things to have. There is no poverty greater than that.

The ‘Me’ versus the Body:

‘This’ is the ‘not turning up’ of the one who is attached to, inside, and having, a body. Without ‘me’, the seeming body is just allowed to be as it is. It’s not ‘mine’,

When there is no ‘one’ to be attached to the body, there is no longer any judgement or criticism of the body. The entire ‘self-improvement program’ disappears. Everything, including the body, is just accepted. It’s easier with the body when it’s not ‘yours’.

For a lot of selves the body is like a prison. But the body is already empty, and perfectly capable of looking after itself without ‘me’. There is no ‘experience’ of the body being empty; there’s just no longer any inside or outside — it’s all just empty.

All the body-obsession associated with being a physical ed teacher, and the related vanity, is gone. The body pursues pleasure, whether that is ‘good for it’ or not, since the body is no longer ‘my’ body. The body is subject to its conditioning of course. ‘I’ have nothing to do with what it does.

Getting ‘This’:

It can seem really heartless to say that there’s no path or process, nothing the self can do. But once bitten with this message, there is no antidote. You can’t leave it alone.

When there’s nowhere else to go, when ‘this’ is it, and there is no possibility of being anywhere else, it’s the end of any effort to be or do otherwise from what is.

Everything is just what it (apparently) is, and what ‘you’ called ‘yourself’ is just ‘being human’. And everything is just the same ‘being’.

The Loss of Motivation:

One apparent result of the self no longer turning up is an apparent laziness. There is no longer a ‘you’ urging that things be done. So there is less inclination to work or to concentrate doing things. Yet there’s probably more love of stories, because they’re just indulgence, enjoyable for what they are, which is just stories. They don’t ‘mean’ anything.

Even ‘my’ story becomes more enjoyable to tell. There are still emotions attached to the story, rooted in memories, but there is no longer any attachment to the story, even ‘my’ story.

It is such a relief that, without ‘anyone’ around to ‘allow’ or not ‘allow’ anything, life is allowed to just be as it is. This is not saying ‘your’ life will be better or worse. There is no longer a ‘you’ to ‘have’ the life, and judge it.

How the Unraveling of the Self Might Appear:

If ‘self’ dissolves, unravels, becomes more transparent, and starts to feel insecure as ‘the ground starts to fall away’, and you’ve never heard this message to give you context for it, you might even be hospitalized (as suffering from a serious dissociative disorder). If you’ve explored and been attracted to this message, however, so you have the context and language to describe it, it might be less devastating.

With the loss of the sense of self, there can be great fears about ‘losing yourself’ or becoming disconnected from the people close to you. Or there may be just a carrying on as if nothing had happened. With the realization that there are no real relationships between family members (they are part of the loss of everything) this can be overwhelming. And in Tim’s story this ‘dissolution’ was excruciatingly slow, and terrifying.

Yet after all the overwhelming fear and excruciating terror, it was realized that there was and is nothing to be afraid of. Self is afraid of not knowing, but the abyss of not knowing is completely benign. There is bliss in going to sleep now; just a falling into the embrace of nothing. But the fullness and wonder of life is exactly the same as the emptiness of the embrace of nothing.

The End of ‘Personal’ Love and the Emergence of Unconditional Love:

There is no one to be ‘in love’. There is just love. But while there is no longer love ‘in relationship’, ‘this’ is in a way more loving. There is no longer love out of need or expectation or negotiation. In place of such ‘transactional’ love there is unconditional love.

Since there is no ‘you’, ‘you’ can never fall in love. There can be ‘falling in love’, but it doesn’t need a ‘me’ or a ‘you’.

Causality:

There is no causality. Things are the way they are, but not ‘because’ of anything. There does not need to be a reason or purpose for anything.

Being with Other People:

There is seemingly less interest in pleasing and compromising with other people, but conditioning of the body is what it is. It was never ‘me’ doing anything anyway, so very little changes. But it is not terrible being alone anymore. Though being alone with others is somehow more enjoyable than being alone without them.

Trauma:

‘I’ loved the Eckhart Tolle model of the ‘pain-body’ for awhile because it let ‘me’ off the hook. It wasn’t ‘me’ causing the suffering, this model tells us, it was my ‘pain-body’. But the truth is that all humans suffer trauma, deeply and repeatedly, especially in our ‘defenceless’ childhood. It’s just that that trauma isn’t actually ‘yours’.

[end of transcript]

…..

Dave’s thoughts:

I have been profoundly affected by Tim’s comments on trauma over the years — he’s a trained and experienced psychologist, and therefore brings a unique and compassionate perspective to this ‘radical non-duality’ message.

He explains that trauma has a profound affect on all of us, on our conditioning, and on the fears, neuroses and suffering we all feel. The ‘injury’ of that trauma doesn’t magically disappear if the sense of self and separation drop away — memories and conditioning remain. Gradually there may be less neurosis, less anxiety and fear, though the fear of a sudden close call or great danger will still arise instinctively in the body. But by taking ‘ownership’ of ‘our’ decisions, experiences, and judgements, we actually inflict and prolong the suffering and trauma that comes from them, which is tragic. But we have no choice but to do so. You don’t have to have a ‘self’ to be traumatized — but it helps!

So what is trauma, exactly? Psychologists define it as our reaction of profound emotional shock stemming from one event (acute trauma) or repeated events (chronic trauma) that are simply too stressful and horrifying for the person to deal with. It can result in lifelong, debilitating, unpredictable emotional (and sometimes physical) reactions to triggers, dreams, memories and flashbacks, and lifelong incapacities like PTSD, unmanageable addictions, dissociation and depression.

Gabor Maté, the renowned Canadian psychologist and addiction therapist, agrees with Tim’s assessment that we all suffer from trauma; it’s just that some of us handle it better, and some of us are more aware of what it’s done to us. His argument is that (especially in our modern stress-filled world) while it happens to everyone, those who have an emotionally stable infancy and childhood, sufficient to develop a sense of healthy attachment and a sense of autonomy, are better equipped to deal with it, but that our modern society deprives most of us of that early stability and development opportunity. Trauma, he says, is not “what happens to you”, but rather “what happens inside you” as a result of the traumatic event(s), how you self-adapt to its occurrence, to protect and support yourself. That may be suppression of emotion, denial, dissociation, addiction, or some other coping mechanism.

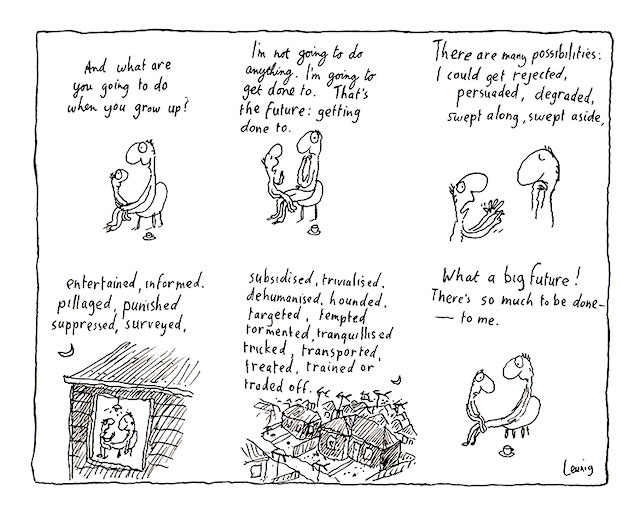

I’m still trying to sort out how trauma, which is ubiquitous in humans, ties into the unique belief of humans, which apparently emerges very early in life, that they are separate beings with selves that control and are responsible for ‘their’ body and ‘their’ lives. Hence giving rise to emotions like shame, guilt, low self-worth, chronic anxiety, indiscriminate and irrational hatred, and so on — emotions that wild creatures, lacking this sense of self and separation, apparently don’t feel.

But, horrifically, humans have induced all the symptoms of stress-related trauma in wild creatures in the laboratory. So trauma is not uniquely human, even though the ‘self’ apparently is. The common variable, of course, is acute or chronic stress. What does all that mean for the effect of (the illusory) self on humans’ unique proclivity for gleeful violence, and for such disconnection from the natural world that we have irrevocably destroyed our planet’s capacity to sustain life, including human life? I have no idea. Maybe it’s a question that cannot be answered.