Sketch of Dr House (Hugh Laurie) by Dutch artist Jessie145 What It All Means This Week: Monbiot’s Global Warming Solution is Already Out of Reach: George Monbiot’s Heat prescribed a radical but feasible way to prevent the more catastrophic effects of global warming, based on years of dedicated research. When I reviewed the book I praised Monbiot for his imaginative plan, but doubted it would ever be implemented. Now Monbiot has acknowledged that it won’t, in an editorial full of desperation and despair. ‘Psychopathic’ Chinese Corporatists Tell It Like It Is: Unlike the deceitful corporatists of affluent nations, Chinese corporations own up to their psychopathy: They put toxic ‘protein’ in pet food because they can get away with it, and because it’s profitable. They know it kills, and has zero nutritional value. They likewise poison cosmetics, household products and human foods, including baby foods. That’s their job: make it cheap, maximize profit for shareholders. No conscience necessary or permitted. In affluent nations, corporatists clamour for deregulation, and bribe and bully corrupt governments and regulatory agencies not to enforce existing laws, and to grant them immunity from prosecution by the public, so that they can do the same. They’re just doing their job. What will it take before the free-market lovers realize the madness of the modern corporate model? Why We Don’t Act Until It Is Too Late: Today’s NYT has two editorials that merit some reading between the lines. The first, on the US health care system (available only to premium readers) argues that as dysfunctional as the US health care system is, it is human nature not to fix it until it is utterly broken. The second argues that we can and should take some relatively simple technological steps that will go a long way to addressing global warming, easily and painlessly (the report referred to is here). Of course, not only is it our human nature to do nothing about global warming until we see its horrific effects (just as we did nothing to prevent New Orleans from the inevitable Katrina until it was too late) — it is our human nature to do the easy painless stuff and then convince ourselves (although the report says the opposite) that that is enough. Such a strange species we are, doing things that are opposed to our own long-term self-interest (and not doing things that are essential to it). Canada’s Version of ‘Rendition’: The Canadian government justifiably complained when Canadian citizens like Maher Arar were kidnapped by US Homeland Security and transported to foreign torture centres. But we’re learning that Canadian authorities’ hands are far from clean when it comes to ‘rendition’ activities. We’ve learned that the Canadian RCMP was complicit in the Arar affair, though the cover-up continues despite a government apology and payment to Arar (no charges of negligence, incompetence or malicious prosecution have been laid against the RCMP perps who set up Arar). And now we learn that Canada’s ‘peacekeepers’ in Afghanistan have been turning their captives over to Afghan torture squads, with the full knowledge of the Canadian Minister of Defence Gordon O’Connor and the Canadian chief of defence staff Rick Hillier. This is a blatant violation of the Geneva Convention, and puts Canadian troops in enormous danger (not to mention blackening the reputation of Canadian citizens). The 100 Mile Diet: Don’t Tell Me, Show Me: Novelist Barbara Kingsolver has often used her stories to convey an activist message, and we know how much more powerful a story can be than an editorial. Now, she’s written a non-fiction book on eating locally, but in her own style, she presents it as a personal story of her family (and others’) struggle to live on locally-raised food alone, and avoids the tendency to prescribe action for readers. As in her novels, her way of making her point is by showing what’s possible, rather than telling what’s necessary. Environmentally Friendly Tissues: Kleerkut lists the brands of toilet paper (anyone learned the Sheryl Crow ‘one square’ trick yet?) and tissues that don’t come from ravaging old-growth forests. Thanks to Dale Asberry for the link. Thought for the Week: There are some strange synchronicities occurring in my life these days, that I’ll speak more about as they emerge in the next few weeks. But Andrew Campbell has just sent me a passage that he ascribes to Jung that speaks of synchronicity, so it is naturally the thought for the week: I am about to publish a little book on one symbolic motif only and you will find it hair-raising. I had to study not only Chinese and Hindu but Sanskrit literature and Medieval Latin manuscripts, which are not even known to specialists, so that one must go to the British Museum to find the references. Only when you possess that apparatus of parallelism can you begin to make diagnoses and say that this dream is organic and that one is not. Until people have acquired that knowledge I am just a sorcerer. They say it is un tour de passe-passe. They said it the Middle Ages. They said, ‘How can you see that Jupiter has

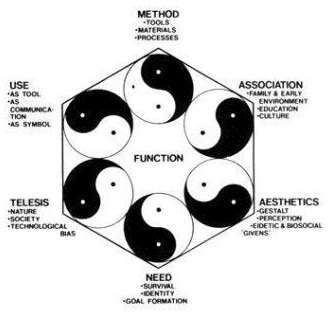

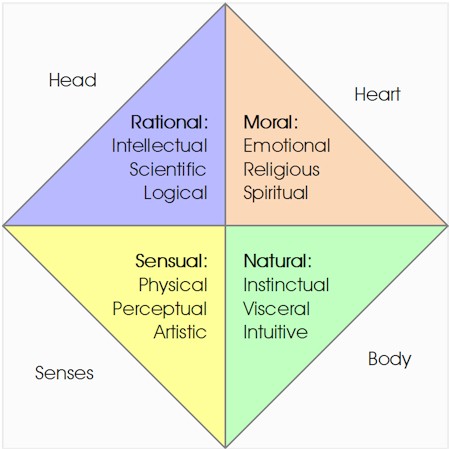

satellites?’ If you reply that you have a telescope, what is a telescope to a medieval audience? I do not mean to boast about this. I am always perplexed when my colleagues ask: ‘How do you establish such a diagnosis or come to this conclusion?’ I reply: ‘I will explain if you will allow me to explain what you ought to know to be able understand it’. I experienced this myself when the famous Einstein was Professor at Zurich. I often saw him, and it was when he was beginning to work on his theory of relativity. He was often in my house, and I pumped him about his relativity theory. I am not gifted in mathematics and you should have seen all the trouble the poor man had to explain relativity to me. He But one day he asked me something about psychology. Special knowledge is a terrible disadvantage. It leads you in way too far, so that you cannot explain any more. You might allow me to talk to you about seemingly elementary things, but if you will accept them I think you will understand why I do reach such and such conclusions. I am sorry that we do not have more time and that I cannot tell you everything. When I come dreams I have to give myself away and to risk your thinking me a perfect fool, because I am not able to put before you all the historical evidence which led to my conclusions. I should have to quote bit after bit from Chinese and Hindu literature, texts and all the things that you do not know. How could you? I am working with specialists in other fields of Psychology can learn no end from old civilizations particularly from India and China. A former President of the British People may say: What a fool to say causality is only relative. But look at modern physics! The East bases its thinking and it evaluation of facts on another principle. We have not even a word for that principle. The East naturally has a word for it, but we do not understand it. The Eastern word is Tao. My friend McDougal has a Chinese student, and he asked him. – ‘What exactly do you mean by ‘Tao?’ Typically Western! The Chinese boy explained what Tao is and he replied: ‘I do not understand yet’ The Chinese went out to the balcony and said. ‘What do you see?” I see a street and houses and people walking and tramcar passing’. ‘What more?’ ‘There is a hill’. ‘What more?” Trees’ ‘What more?” The wind is blowing’. The Chinese threw up his arms and said: ‘That is Tao’. There you are. Tao can be anything. I use another word to designate it, but it is poor enough. I call it synchronicity. The Eastern mind, when it looks at an ensemble of facts, accepts the small quantities. You look, for instance, at this present gathering of people, and you say: ‘Where do they come from? Why should they come together?’ The Eastern mind is not at all interested in that. It says: ‘What does it mean that these people are together?’ That is not a problem for the Western mind. You are interested in what you come here for and what you are doing here. Not so the Eastern mind; it is interested in being together. It is like this: you are standing on the sea-shore and the waves wash up an old hat, an old box, a shoe, a dead fish, and there they lie on the shore. You say: ‘Chance, nonsense!’ The Chinese mind asks: ‘What does it mean that these things are together?’ The Chinese mind experiments with that being together and coming together at the right moment, and it has an experimental method which is not known in the West, but which plays a large role in the philosophy of the East. It is a method of forecasting possibilities. – This method was formulated in 1143 B.C. When people ask me “How can you possibly believe that our civilization is in its last century?” I try to tell them. I point them to my Save the World Reading List to explain what research and study I have done on the subject (my intellectual knowledge). I point them to all my writings, in sequence, on the environment and the state of the world that let me think out loud to formulate what I believe (my emotional knowledge). I take them out for a walk in the forest next door and let them see and feel and smell and taste and hear what all-life-on-Earth is telling us (my sensory knowledge). And I confess that instinctively, too, I know this to be true (though that knowledge cannot be imparted because to do so would require others to trusts my instincts). It is the synchronicity of these four types of terrible knowledge, all converging on the same ghastly truth about our future, that has led meto this conclusion. And then I shrug and say that I can’t explain it any better than that. I just know. I have been ‘led in so far I cannot explain any more’. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Jason Godesky at

Jason Godesky at  I‘ve been a member of the Green Party for many years, but I’ve frequently duelled with them over their preoccupation with getting candidates elected rather than getting good legislation passed. In Canada, although ‘private members’ bills’ have an uphill battle to get time on the legislative agenda, they are often introduced and occasionally even passed into law.

I‘ve been a member of the Green Party for many years, but I’ve frequently duelled with them over their preoccupation with getting candidates elected rather than getting good legislation passed. In Canada, although ‘private members’ bills’ have an uphill battle to get time on the legislative agenda, they are often introduced and occasionally even passed into law.  What I’m planning on writing about soon:

What I’m planning on writing about soon: