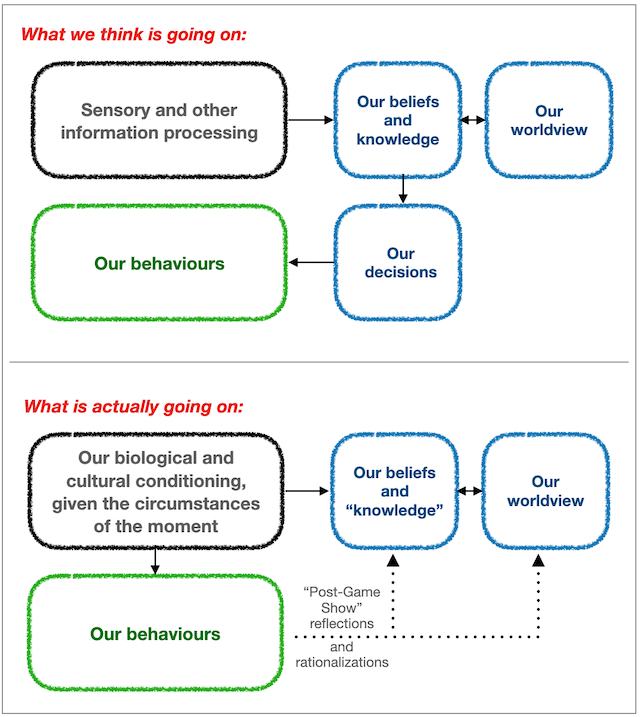

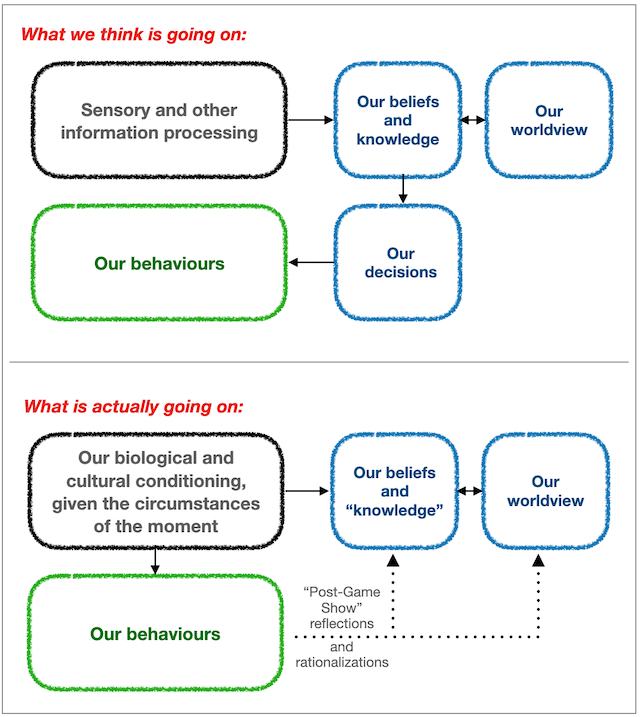

Yep, that annoying graphic again. If the subject of free will and conditioning doesn’t fascinate you, give this post a pass.

There is something terribly counter-intuitive about the idea, contained in the above graphic, that while our behaviours can condition other people’s beliefs and behaviours, our beliefs affect neither our own behaviours nor anyone else’s. Our beliefs merely rationalize, and attempt to make sense of, past behaviours.

Let’s consider a specific example:

I have come to believe that the meddling of the US government, its political establishment, and its ‘intelligence’ agencies were directly responsible for the Ukraine coup of 2014, and the subsequent 2014-2022 civil war, the failure of attempts at détente with the Minsk Accords in 2014-15, and since 2022 the last-ditch all-out proxy war between Russia and the US/NATO.

This is not a popular belief. I was conditioned to believe this, mostly, by stuff I read, and had been reading, well before the 2014 coup. As a result I was flabbergasted at the reaction, in the western media, and among almost everyone I know, to the Russian invasion in 2022 — reaction that presumed that the Russian invasion was completely unprovoked, unwarranted, and the act of an “insane” leader “clearly” striving to recreate a Russian empire. No matter what information I provided to people, they dismissed it as “Russian propaganda” and dug in to what to me was a completely irrational, untenable belief. Based on the uniformly Russophobic reports they read in the media starting in 2022, it seemed, they had already made up their minds. Nothing would change them. They knew nothing of what happened leading up to the war, and mostly didn’t care.

The only difference between their beliefs and mine was (and is) that they were conditioned by a completely different, and irreconcilable, set of behaviours of other people, notably people speaking and writing in the media.

I need to clarify here that what people say is a subset of what we do. Speech, and writing, are behaviours. Presumably these behaviours are somewhat congruent with our belief systems and worldviews, but that is not the point. The point is that other people’s behaviours condition our beliefs, but not the other way around.

Here’s how I think the illusion that beliefs affect/condition our behaviours arises: When someone writes an article in the newspaper accusing Russia of atrocities in Ukraine, one would expect that their words would ‘reflect’ their beliefs. But while that is a reasonable assumption (especially if you believe in free will, and that there really is a ‘self’ making decisions that are then enacted by the body, including the writing of articles), there is another explanation for what is really happening: The writer of the article was conditioned, not by their own belief system, but by the actions (behaviours) of others — other people’s writings, news reports, conversations etc — conditioned to want to write an article explaining their beliefs and worldview about Ukraine. The actions of other people have conditioned (‘informed’) the writer’s beliefs and worldview about Ukraine, and it is those actions, not his (or anyone else’s) beliefs, that prompted the writing of the article. That seems convoluted, especially when we’re taught to believe in free will and the causality that arises from it. But it does explain plausibly what actually happened.

Likewise, when I write anti-US/NATO Empire articles on my blog, that writing is not conditioned by my (very different from the western mainstream) worldview about Ukraine, but by my dismay at the behaviours/actions of the western media, and of my friends, in their (to me) bizarre arguments in support of Empire propaganda that are (to me) patently misinformed and untenable. It is not my anti-Empire worldview that conditions me to write (often very unpopular) articles on my blog; it is entirely the actions of others that I am reacting to (as I have been conditioned all my life to do when I hear what I believe to be dangerous falsehoods).

Here’s the counterargument: Isn’t that ‘belief’ that these claims are falsehoods at least partly conditioning that reaction? Surely, if my belief system and worldview weren’t involved in separating ‘fact’ from ‘fiction’, I would have no compulsion to get upset. Doesn’t that mean that my belief system and worldview are conditioning my behaviours?

That’s where I, and some of my friends and readers, have questioned the veracity of the “What is actually going on” chart above.

To refute this counterargument, I think we have to step back and ask what exactly are beliefs? In physical terms (neuron states and electro-chemical reactions), what is the “physiology” of a belief? I have argued that conditioning is simply the process of influencing the billions of cells and trillions of atoms that make up the body (including its brain) in ways that drive it to behave in a certain way, prompted largely by the apparently universal evolutionary propensity of life to maximize pleasure (dopamine hits etc) and minimize pain. And our behaviour is all conditioned electro-chemical activity as well — when we move, or speak, or write, billions of parts of our body do what they have been conditioned to do, and they can do nothing else. If there is indeed no such thing as ‘free will’ then, as I’ve argued elsewhere, there cannot be such a thing as a ‘self’ controlling or influencing this conditioning.

I read through a ton of articles on the physiology of beliefs and, unsurprisingly to me, doing so was a complete waste of time. Everything I read was just theories and opinions, psychobabble papered over with fuzzy coloured fMRI photos of brains that attempt to add credibility and evidence to completely unsubstantiated and unsubstantiatable theories, opinions, and ‘models’. They no more present any real science (eg these theories are not falsifiable, as any legitimate scientific theory must be, and they do not have enough substance or evidential support to be any more than mere opinions) than does phrenology (which a lot of so-called neuro’science’ alarmingly resembles).

So let’s start with a simple theory/opinion (and yes, I acknowledge and agree that what I’m laying out here is just a theory, and my conclusions are no more valid than the theory, which is itself neither provable nor falsifiable). Bear with me nevertheless.

The theory is that the idea of the human ‘self’ is at the centre of a model (a representation or map) of reality concocted in the brain for the purposes of ‘making sense’ of the electro-chemical signals it receives. The model conceives that there is the ‘self’, and then there is everything else outside it, starting with the body the ‘self’ imagines itself to inhabit and control. Its beliefs, worldview and ‘knowledge’ — what it thinks it ‘knows’ — constitute its current best guess, based on those inputs, of what is real and separate, and how all these real, separate things seemingly interrelate. This model is constructed based entirely on these inputs ie it is completely conditioned. And over our entire (apparent) lives, that conditioning will change, and our brains will alter the beliefs, knowledge and worldview captured in this model accordingly.

So in some brains, the concept of Putin (ie the brain’s beliefs and ‘knowledge’ about him) will be of an evil, deranged war-crazed megalomaniac with delusions of grandeur. In other brains, differently conditioned, the concept of Putin will be of a guy caught between (a) western powers trying to destroy his country so they can steal all its resources and remove it as a threat to the Empire, and (b) a domestic populace insistent that Russia has a duty to defend and protect the mostly Russian-speaking people of Crimea and the Donbas who were (for complicated and political reasons) incorporated as part of the nation of Ukraine — a nation which has, for quite understandable reasons, a long history of hatred and antipathy for Russia.

Each of these beliefs about the situation in Ukraine is ‘stored’ somehow in the brain as a collection of neural states, synapses, and electro-chemical conditions and impulses. Despite a plethora of neuro’scientist’ theories, models and opinions, we have no idea how these beliefs are actually stored or represented in the brain.

So, in my case, when I read op-eds about how crazed Russian troops (and their commanders) are committing evil atrocities out of sheer hate and blood-lust, I am compelled (conditioned) to write about these nonsense charges (and no, I’m not going to go into that in this article).

That is my conditioning — to write about this, even at the risk of alienating and annoying my small group of readers. Where is this impulsive conditioning coming from? Is it from the desire to bridge the huge intellectual disconnect between these monstrous allegations and my worldview of what is actually happening in Ukraine? Or is it rather this body’s conditioned, instinctive, visceral fear that horrific lies of this nature have often in human history preceded conditioned, mindless, bloody, out-of-control violence, and, when unchallenged, have also conditioned virulent and irrational hatred that lasts generations, is almost impossible to heal, and can quickly spark into traumatizing violence at any time? (Especially when both sides are nuclear powers.)

I would argue that while my worldview about the situation in Ukraine would likely support my belief that these lies are dangerous and endlessly damaging, that is not what provokes me to write about them. My beliefs about Ukraine and every other subject with which I have no direct personal knowledge, contact and experience, are actually pretty fluid. I’ve ‘changed my mind’ about a lot of things, some of them pretty contentious and controversial. Or, rather, conditioning by other people has ‘changed my mind’.

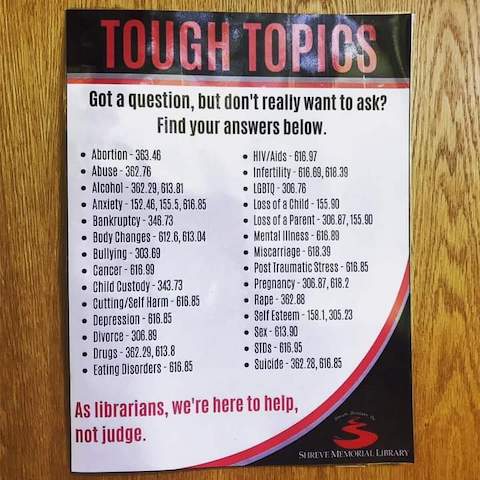

I was brought up to hate and fear lies and lying, and dishonesty and deception of all kinds (hence my conditioned dislike for advertisers, marketers, PR firms, ‘perception managers’, ‘reputation managers’, and other professional liars). I can’t say quite why that was, though I can speculate. My father was a journalist, and he was rather obsessed with the truth, but he was also a frequent sucker for con artists. When I first entered the school system I was utterly shocked (some might say traumatized) to discover both other children and teachers blatantly lying all the time — something I’d never experienced before. At one point I was called into the principal’s office and told to apologize for correcting an untrue statement from my teacher. (There are many more examples of how I was conditioned by others’ behaviours to abhor and fear lying, deception and manipulation of every kind; I don’t even like listening to debates.) Complete honesty has always been an essential requirement in every relationship I have had in my life.

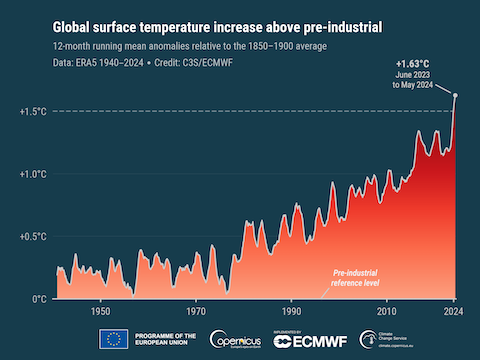

So now, when I read what I perceive to be outrageous lies and disinformation about the situation in Ukraine, or Gaza, or China, or any of dozens of other places and people, my reaction is immediate and visceral. For example, I’ve watched the proportion of citizens across all the countries of the west who say they have an “unfavourable” rather than “favourable” view of China, rise from 20% to 80% over the past two decades. This seems to be entirely the result of relentless Sinophobic and xenophobic fear-mongering and misinformation campaigns — we’re that susceptible to conditioning by liars.

Of course, all of the above is just my rationalization, trying to bring my beliefs, and some of the reasons I have for them, to bear on an emotional, visceral response (ie writing what I have learned about these countries) that actually has absolutely nothing to do with my beliefs or worldview or knowledge about Ukraine, or Russia, or Gaza, or Iraq, or China. WTF do I even really know for sure about what’s going on there? I’ve spoken to people who live there, and read books that go into detail about life there, but that doesn’t qualify me as anyone who could pontificate about the “truth” in those countries.

No, what is provoking my articles is my deeply conditioned fear, anger, and loathing of liars who have provoked or are provoking horrific violence in these and other countries. The “facts” I present to call out the lies are irrelevant, and in any case the facts are very unlikely to change anyone’s behaviours or beliefs about these situations.

What we each do (including what we say and write) has a parallel conditioning effect on other people’s beliefs and on their subsequent actions. That effect is usually a very small one. But sometimes that effect can be powerful, such as my recent experience with the Free Palestine protester I shared an elevator ride with who told me, somewhat reluctantly and tearfully, that his daily protesting is because he’s personally lost 55 family members in the genocide in Gaza.

But while our and others’ actions can change our beliefs and worldviews, our beliefs and worldviews themselves have absolutely no effect on our subsequent actions. If I join the Free Palestine protest, it’s because of the elevator incident, not because of my already extant beliefs and worldviews about the genocide.

If you’ve read this far, you probably remain unconvinced that there is no solid two-way arrow connecting “our beliefs” and “our behaviours”. I’m not sure I’m entirely convinced myself. It’s contrary to everything I’ve been taught all my life, and its counter-intuitive to boot.

If I were to be suddenly persuaded that my worldview about the situation in Ukraine was deeply misinformed, then I would, I think, be quite willing to add it to my list of all the things I’ve ‘changed my mind’ about, and shut up about it, as I did about squalene, the sixth tower, and the “genocide” of the Uyghurs. I was wrong about those things. The behaviours of others (writing and talking about these issues) changed my beliefs.

But if I did ‘change my mind’ about Ukraine, I’d be writing and talking about the new information I’d received in order to consequently ‘make sense’ of what has actually happened — of the behaviours of others which led me to doubt and then change my beliefs about this issue. My beliefs would not have affected my writing and behaviours; it’s the other way around.

Let’s consider another example: Someone cuts me off in traffic and I have to swerve and brake suddenly to avoid an accident. I don’t need a model of my beliefs and worldviews about traffic courtesy in order for my body to react as it does. The instinctive fear and anger arises after my behaviour change, and then comes the judgement about the other driver. Even if I go home and rant about the driver afterwards, that rant was prompted by the driver’s actions, not by my belief system about it.

And another example: Suppose everyone I know and everything I’ve read supports the belief that the dictator of some little-known country X is utterly corrupt and has caused untold suffering to the country’s citizens. I would probably (at least tentatively) ‘add’ that belief to my worldview.

If I were then asked by a close friend to attend a demonstration against the dictator, then whether or not I accepted would be determined by the actions of my friend, not by my personal worldview about the dictator. Behaviours affect and condition my worldview, not the other way around.

If someone I trust then asserts, with credible evidence, that this dictator is being demonized by vested western interests to facilitate his overthrow so western corporations can steal the country’s important resources, then it’s those behaviours that will instil doubt, anger and fear in me, and, if found credible, alter (ie condition) my worldview. At no time will my worldview affect my behaviours. My worldview is, after all, just a model, a map, a representation. The post-game analysis.

And, as a further example, there is considerable evidence that wild creatures do not have belief systems or worldviews; they don’t need them. If they are deceived, eg when a tester in a lab withholds a treat after previously rewarding a particular behaviour, they will get annoyed. It will be the tester’s behaviour that conditions the annoyed response, not the worldview of the creature that judges the deception to be unfair or hostile. Our reaction to deception need be no different.

I sometimes (still) read vituperative attacks on Russia, on Palestinians, on China and on other nations in the mainstream media. I don’t think the writers of these attacks need to be coerced or bribed to write what they do, even though, based on my reading and research, what they write are really unpardonable lies. These writers really believe what they are writing. They can read the same document I do and get a directly contradictory understanding of what it says. That’s their conditioning. When their writing makes me angry, it is more their conditioning (and my fear of what, en masse, such misinformed conditioning can lead to) that upsets me, not ‘them’ personally, or my ideas and beliefs about them. They can, after all, only act on their conditioning, which they clearly share with a large circle of people who reinforce each other’s (IMO misinformed) beliefs — or else their writing wouldn’t be so strident.

That’s what’s so scary. That the lies so often go unchallenged. And what happens when whole nations of lied-to people do not challenge what they’re told? We’ve seen it before. We’re seeing it right now.

Returning to the physiology of conditioning: When we lift our foot suddenly after stepping on a nail, or when we swerve when suddenly cut off in traffic, a series of electro-chemical activities produce our body’s reactions. There is no time for the model of reality that constitutes our belief systems and worldview to play any role in it. It’s hard to imagine how this model of reality, sitting in our brain, the result of the human brain’s incessant and frantic effort to try to make sense of everything, could ever actually influence (condition) our behaviours. How would it do so? By what physical process could my mental model of beliefs about the situation in Ukraine possibly prompt this body to sit here and type an essay about it?

If I write about it, it is because others’ actions (including conversations and writings) have alarmed me enough that I feel compelled to ‘think out loud’ on these pages. Writing this blog may change my beliefs. But what I write has been conditioned by others’ actions, not by my beliefs. Behaviours are the horse, and beliefs are the cart. The cart cannot pull the horse.

Well, you may still not be persuaded, you poor souls who’ve read this far. As I say, it’s just a theory. Best I’ve got. Makes sense to me. For now.

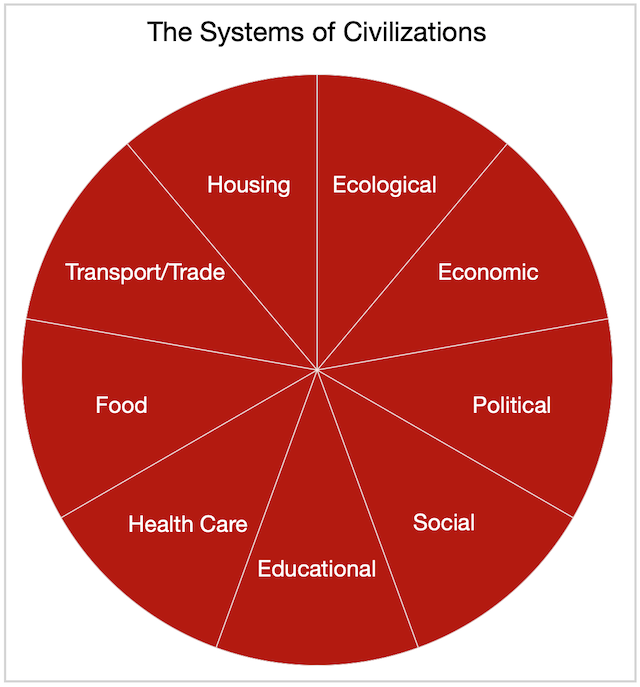

Why does all of this matter? For me, it’s all about trying to dispel some of the enormous cognitive dissonance of a world that apparently reacts only to conditioning even though its humans believe fiercely that they have free will and control, and judge everything that happens accordingly.

Of course, those dissonant beliefs were entirely conditioned, and ‘we’ cannot do or believe otherwise. Our mental model, the one whose maintenance consumes so much of our time, energy and concentration, is fatally flawed. It is ‘misinformed’ about the nature of reality, about what’s really going on in the world, and our interactions with other humans merely reinforce and entrench these misinformed beliefs. No wonder we’re so unhappy! Based on our model, nothing makes sense.

There are some humans (some of whom I’ve listened to, and in some cases spoken with, at length) for whom this model no longer exists. For them, it was suddenly obvious that there is no ‘self’. For them, thoughts (including beliefs) and feelings may arise, but they have no traction; they don’t ‘belong’ to any ‘one’, they don’t ‘mean’ anything, and they don’t have to mean anything. These humans remain completely functional, just as wild animals are completely functional, without the need for the concept of a self and a system of beliefs and worldviews. They do what they are conditioned to do, as we all do. If you met them, or even if you knew them ‘before’ their selves seemingly disintegrated, you would not be able to distinguish them as being different from anyone else, or different from how they were ‘before’.

They assert that they ‘know’ nothing, and that nothing in fact can be ‘known’ (when they use the term ‘known’, they are referring to facts, and “truths”, and beliefs, not technical know-how). For them, the blue squares in the diagrams at the top of this page simply do not exist; there is only apparent conditioning, and apparent behaviour. The internal logic and consistency of what they say is ‘seen’ ‘there’ is (to me at least) indisputable, (and I’m notoriously skeptical); it is not a theory. They also assert that there is no ‘path’ to seeing this. The useless bit of mental software in the blue squares above either seems to be real, or it doesn’t, and for them, it doesn’t. They’re not selling anything, just telling it like it is ‘there’. I have no reason to doubt them. And their message is so consistent across dozens of these ‘radical non-duality’ messengers, and over decades, and so impervious to criticism (I’ve been trying for eight years to find holes in it), that it is unfathomable to me how (and why) they could be just making it all up.

If everything in ‘our’ blue squares is just a concoction, a misunderstanding, an illusion, then obviously it cannot affect or condition anyone’s behaviour. Conversely, if our blue square stuff (our beliefs and worldview) does have a real-world effect on our behaviours, then my radical non-duality friends (who have no blue square stuff) must be uniformly and categorically deluded in their perceptions of the entire nature of reality.

Hence the cognitive dissonance, and my efforts to convince myself that our beliefs do not affect or condition our behaviours.

You don’t need a map to get from anywhere to anywhere else; there are lots of ways to get around without them. If you have a map that is accurate, it can be useful. But if the map you have doesn’t even come close to representing the territory you’re trying to navigate, then you use it at your peril.

What would we be — what are we — without selves, without beliefs, without knowledge, without worldviews?

I have no idea. I am starting to appreciate that I know nothing. But at this point, if I were to guess, I might say, insanely: There is no self, no ‘we’. There is just what appears to be happening. Just this.