image from piqsels, CC0

My last article talked about how we’re biologically and culturally conditioned to love the music we love (and perhaps the people we love). This time around I want to explore the shadow side of this — how our biological and cultural conditioning ‘teaches’ us to hate and fear, and how we can be ‘groomed’ to hate and fear even more.

The thesis is basically the same: We have no choice, free will or control over what we think, believe and do. Everything we think, believe and do is a result of our biological and/or cultural conditioning, given the immediate circumstances of the moment.

So, for example, our attraction to potential partners is mostly due to our body’s chemical ‘reading’ of the appropriateness of the other person (appearance, health, fitness, genetic compatibility etc), to produce healthy offspring, and only secondarily to what we have ‘learned’ (ie been culturally conditioned by our own and others’ personal life experiences and learning) to want and not want in a potential partner. It is not a ‘rational’ choice; in fact, it is not a choice at all.

Our political worldview, on the other hand, is mostly culturally rather than biologically conditioned. It is determined primarily by the aggregate views and opinions of the people we have lived, worked with, hung out with, and heard or read in our studies and in ‘the media’.

We would like to believe this worldview is based on facts and hard evidence, but it rarely is. Our brains tend to form conclusions based on first impressions (which tend to be more emotional than logical), and those conclusions tend to harden in the absence of compelling direct personal experiences or arguments to the contrary. In fact, our brains tend to form hypotheses quickly, and to reject evidence that undermines our belief in those hypotheses, so that most of what we think of as our ‘beliefs’ are really just largely unsubstantiated opinions subject to a host of cognitive biases. We are inherently credulous until we form an opinion on something; and then we are resistant to changing that opinion.

There is nothing ‘wrong’ with this irrational brain behaviour. It has evolved in humans because it appears to work better than constantly challenging everything to the point we may become paralyzed by indecision and uncertainty.

Hence our worldview is a massively complex phenomenon — Our personal experiences play a role, we condition each other to align our worldviews, our worldviews become entrenched based on early experiences and learning, and external media are continually influencing, and attempting to influence, these worldviews. And the worldviews implicit in those external media are in turn influenced by the worldviews of the ever-changing decision-makers in those media, which are in turn influenced by people those decision-makers encounter. No one is in control.

There is considerable evidence that our worldviews are influenced much more by those we know and interact with personally, than by the ‘media’, especially in this age of enormous media distrust. ‘My buddy Joe’ has no reason to lie to me, and he never has (I don’t think, except maybe that once). The corporate media, by contrast, have all kinds of reasons to lie to me, and they repeatedly have. A recent study revealed that most fans of Faux News enjoy the simplistic reassurances they get from the network, but don’t actually buy a lot of what its clowns tell them, especially when viewers cannot relate the claims to their direct personal experiences.

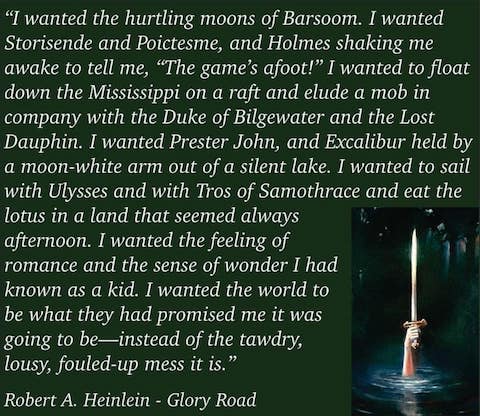

And, as I’ve written here perhaps too much, we tend to believe what we want to believe, regardless of whether it’s true or not. We want to believe we can do and become anything we set our minds to, which is essentially preposterous. Why do we believe it then? Because it’s just too depressing to believe otherwise. We don’t want to believe our current civilization is in a state of (human-caused) accelerating collapse that will cause our descendants unimaginable suffering, because accepting that would fill us with feelings of guilt, shame, and hopelessness. Our beliefs, therefore, reflect what we feel (and want to feel, and what we don’t want to feel) far more than they reflect what we think.

The term grooming has recently been repurposed to mean “manipulating someone until they’re isolated, dependent, and more vulnerable to exploitation”. Isolated to make them believe that they can’t talk to others ‘outside’ about their situation (what eg QAnon and other cults do), dependent to make them believe they can’t get away from the situation, and hence vulnerable to more manipulation. It’s a form of psychological imprisonment to instil learned helplessness, in this case helplessness to believe or do anything other than what the groomer wants.

The word grooming was first appropriated, quite powerfully, by foes of spousal abuse to explain the psychopathic processes used by abusers. Since then it’s been used to describe the processes used by child molesters to ‘soften up’ their victims’ resistance to abuse, by right-wing book-burners like Ron DeSantis to malign teachers and parents who want children exposed to new ideas that are contrary to right-wing orthodoxy, and by progressives to disparage right-wingers who want to restrict their children from accessing perspectives other than their own long-held positions.

What it all comes down to is the desire of the groomers (or alleged groomers) to control or influence the conditioning of the ‘groomees’. This desire is what underlies almost all propaganda, censorship, and mis- and disinformation campaigns. It is the core business of marketing, PR, advertising, self-proclaimed ‘influencers’, and ‘reputation management’ organizations. And it is the raison d’être for social media ranking algorithms. If my thesis about conditioning underlying all of our beliefs and behaviours is correct, this is a very important business, enough to warrant the trillions spent on it each year.

The question is: Is it really possible to condition someone to believe or do what they wouldn’t have believed or done anyway? It does seem to be possible when it comes to children, especially if they’re isolated from saner voices. (Makes you think about the whole business of parenting.) And it does seem to be possible in controlled cult environments (both physical ‘compounds’ and virtual ‘echo chambers’). And the relentless campaigns to persuade the public of the veracity of lies about Ukraine, Russia, China, Iran etc show remarkable success, judging by subsequent opinion polls.

So what’s going on here? Are we all so credulous and gullible that our worldviews are up for grabs by the wealthiest, most powerful, and craftiest propagandists and marketers? Can we be conditioned not only to buy shiny, cleverly-marketed, environmentally destructive, unhealthy crap we don’t need, but also to fear and hate certain groups to stoke division, polarization, further oppression, and thirst for violence and war?

The answer to both questions, worryingly, is probably Yes, to a point. The PMC top-caste, a relatively small group, may be hell-bent on war with China, but most people in the US/NATO bloc seem, while persuaded of the Chinese government‘s maleficence, unwilling to lay down their, or their children’s, lives to combat it.

Most, I think, have been persuaded that the Chinese government is ‘evil’, because:

- This belief doesn’t obviously conflict with their own, limited, direct personal experiences;

- Their peers haven’t spoken up on the subject one way or the other;

- The media they read have not offered any conflicting point of view, and have written ad nauseam and in one voice about the ‘plight’ of China’s supposedly oppressed Uyghurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongese.

- They’ve never lived in or visited China, so they have no idea what life there is like; and

- They have few or no Chinese friends or acquaintances who’ve said anything about it.

This results in what I would call a ‘soft’ worldview position on the ‘evilness’ of the Chinese government. (It was my own position until a few years ago, when I actively started to learn more about it. I’m definitely not proud of that.)

Such a position (“Their government is seemingly awful, expansionist and probably genocidal, but so are many other governments”) isn’t going to change your vote, or cause you to enlist. But it also isn’t going to get you to protest against a war with China. This position is ‘aligned’ with the groomers’, but it isn’t strongly held.

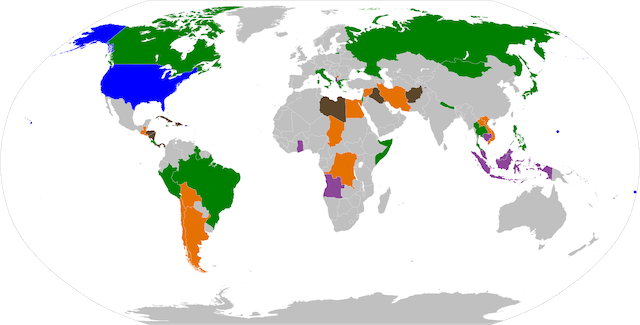

This, however, is all the groomers really want. They want to pre-emptively block widespread public opposition to their planned war. That’s all they need. It was all they needed in Vietnam (until the very end), and all they needed in, among many other countries, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Libya, Cuba, Chile, Venezuela, and now Ukraine.

It doesn’t take a lot to instil fear and hate in a large swath of the population, sufficient to block opposition to a campaign against the targets of the hate-mongers, and to, as Noam Chomsky calls it, “manufacture consent” for a planned action. You don’t have to manufacture support anymore (now that wars are fought mostly with foreign proxies, private mercenaries, drones, and long-distance missiles). You just need to sow enough fear, hatred and anxiety to undermine, sabotage and silence broad dissent.

A coordinated and incessant wave of lies has been used to instil fear and hate against alleged ‘enemies’ for over 60 years: North Vietnam, Vietnam War protesters, Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, the Occupy and BLM protest movements, the ‘red menace’ and ‘yellow menace’, Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, popular socialists all over the world, and dozens more. We are now being groomed to fear and hate the governments (and ‘complicit’ citizens) of Russia, China, and Iran, sufficient to undermine and block opposition to war against them.

Of course, we are also being groomed to hate and fear imagined ‘enemies’ within our countries, leading to what I would describe as a ‘soft’ polarization — not enough to provoke (a lot of) violence, but enough to paralyze any movement towards understanding and working with the internal ‘enemy’.

Contemporary political analyst Aurélien has made the argument that in most parts of the world, “different beliefs exist side-by-side without conflict”. That doesn’t mean they necessarily like each other; they just respect each other’s right to their views as long as they don’t impose them on others. But in the US/NATO bloc, he says, “the dynamic of western culture has [increasingly] been one of a constant tendency towards intolerant, unchallengeable assertions of [absolutist] Truth”. Think of this like a Crusade mentality — any opposing views to Ours must be vanquished by any means necessary.

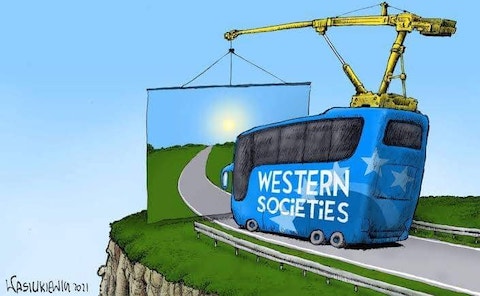

This absolutism brings with it, he says, a set of rather dangerous beliefs: That war is not so much about territory as it is about the moral and intellectual superiority of certain ideas, and that there is therefore a certain unquestionable inevitability about the eventual global ‘success’ of the underlying ideology. He argues that the PMC embraces this ideology with a religious fervour, but is finding it harder and harder, in the face of its increasingly obvious failings (ever-growing poverty, inequality, violence, polarization, intolerance, collapsing infrastructure, economic fragility, anomie etc in the countries where this ideology is based), to sell even their own citizens on supporting the Crusade to make this ideology a uniform, global one).

Hence, perhaps, the need to manufacture consent by seeding fear and hate to undermine internal dissent against this Grand Cause. They might be thinking: “If we can’t get the unhappy citizens to accept that Our Way (untrammelled capitalistic neoliberalism) is the only right way for the world to live, we can use hate and fear to at least bewilder the opposition to our plans, and, since we now control the global purse-strings, we can pursue the Crusade without popular support, as long as they stay out of our way.”

This ties into my earlier post about our inability to admit failure. As the Crusade continues to stumble, the response of the PMC is to double down, ratchet up the propaganda and censorship, and demonize opponents of the cause as enemies.

I need to stress again that this isn’t an organized campaign. The PMC isn’t a cohesive group. But it is an earnest one. And they genuinely believe that those they have identified as enemies, and their ideas, absolutely must be vanquished. They have conditioned each other very well. And they have power and influence disproportionate to their small numbers.

I was struck by the complete hatchet job the CBC did on Canadian Daniel Dumbrill after he agreed to be interviewed about his views on China, where he lives. The CBC reporter in question is young and inexperienced, but showed no signs of zealotry. It was clearly not hard for him to accept the premise of his assignment — that Daniel was either a propagandist working for the Chinese government, or a hopelessly misinformed Communist idealist.

Of course, Daniel is neither, but the worldview of the reporter was completely unable to fathom that possibility. He could not accept that he’d been conditioned to believe a whole series of complete fictions about China. After all, all his newsroom buddies shared his beliefs. They couldn’t all be wrong, could they?

You can see the same blind conditioning in the recent, utterly unprofessional hatchet job a New Yorker reporter did on John Mearsheimer. What John was saying was so incompatible with what all the New Yorker reporters believed, that obviously it had to be John, not them, who was misinformed — or even malevolent.

This is how cultural conditioning works. Everyone involved can believe they know and are speaking the truth, even as they are perpetrating horrific lies with potentially catastrophic consequences.

And we don’t even learn from our mistakes. The current perpetrators of lies about China and Russia include a whole rogues’ gallery of the same fools who, believing they were telling the truth, led the world into the ghastly wars in Iraq. They’ve never acknowledged their lies. They cannot. They’ve been conditioned too well to change, to even contemplate the possibility that they were wrong, and admit their culpability in the resultant disaster.

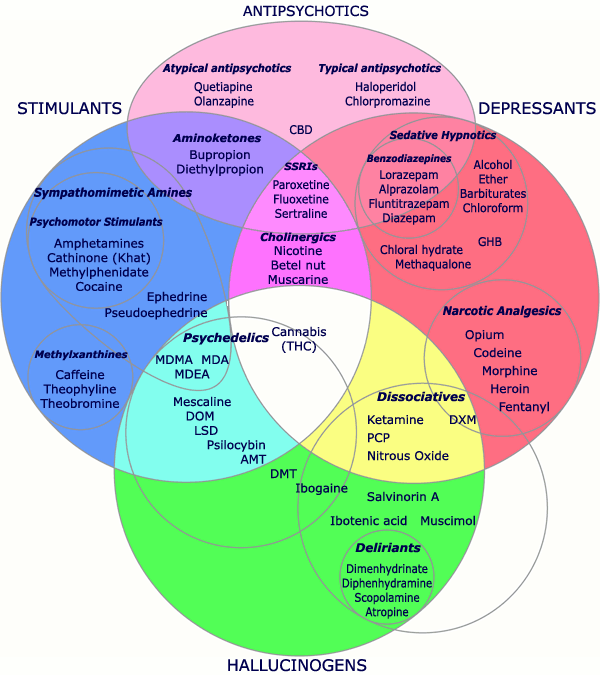

What prompts any of us to feel anger and fear, especially when there’s nothing to be fearful or angry about? In other words, what is the mechanism by which we’re so easily conditioned to hate and fear?

I think it plays off a number of very human foibles:

- We’re afraid of thinking ourselves ignorant (and of being thought of as ignorant), and hence being vulnerable to manipulation or exploitation. So when we’re given a simple (and possibly wrong) answer and reassured that that it’s “all you need to know”, we are all too eager to accept it.

- Unfamiliarity breeds fear and contempt. In many cases, even if we live in culturally diverse places, we know no one from cultures other than our own, and little or nothing about other cultures. That’s easy to exploit by planting distrust, suspicion, and untruths about the unknown “other”.

- We kind of enjoy righteous indignation. It makes us feel like we’re on the ‘right side’, that we’re knowledgable, and that our easily-inflamed anger and fear is justified.

- If we hear something repeated often enough, especially if we’re never exposed to anyone refuting it, we are inclined to believe it must be true.

- We have an inherent desire to know things. It’s comforting, and often carries with it a certain degree of prestige.

- We really do loathe complexity. Uncertainty and incomprehensibility displease us. We much prefer simple, unquestionable, black and white “truths”.

- We are easily frustrated when we perceive a situation is out of control (and out of our control), or when we feel a sense of impotent moral outrage (“it shouldn’t be like this”), or when we feel helpless or powerless. That can quickly manifest itself in anger, in fear, and in hatred — since hatred is often a projection of anger to a class of people, creatures, ideas or things, and more often than not a mask for fear.

These reactions and behaviours are all perfectly understandable, and evolutionarily selected for. But they’re also easy to exploit.

And so, we are played, conditioned, groomed, exploited, and manipulated. Mostly, we do this to each other, mostly unintentionally, infecting each other with hate and fear. Sometimes this is done to us by politicians, by the media, or by PR and other organizations paid to incite it.

And sometimes this will provoke us to actual acts of violence. More often, though, it is enough for the perpetrators (who, remember, almost always really believe the incendiary untruths they are provoking us with) that we be sufficiently knocked off balance that we don’t resist, interfere, object, or dissent, but instead that we suspend judgement and action, and be passive. So that the perpetrators, righteous Crusaders all, can do what they want to do (in ‘everyone’s’ best interest, of course), until it’s too late to stop them.