Trump as Canute, ordering back the waves; my own prompt*

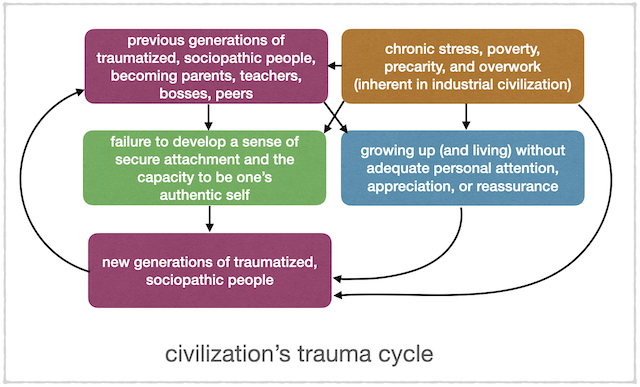

Aurélien has written a series of articles recently on the subject of competence, or, more specifically, its absence in our globalized civilization culture. As many of our political, economic, social, educational, health and other systems teeter, and in an increasing number of cases (and places) collapse, competence naturally becomes harder to come by. It’s hard to keep your wits about you when everything around you is falling apart.

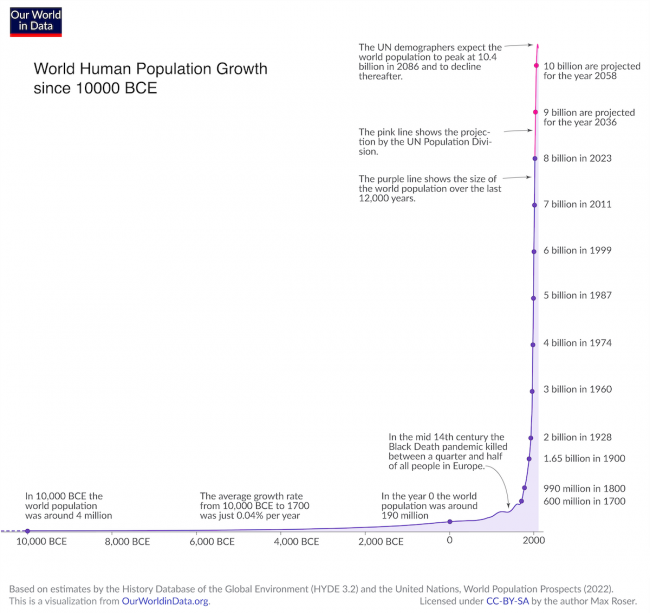

These systems have grown in size and complexity to the point that they can no longer provide what they were designed to provide. And as Jared Diamond, Ronald Wright and others have explained, all civilizations inevitably collapse when they reach this stage. There is no bringing collapsing systems back from the brink, no matter what Hollywood might tell you.

This drop in learning, skill, and experience in positions of authority is coming, Aurélien suggests, at exactly the time we need competence more than ever.

One need only look at what passes for leaders in pivotal positions of power these days to see how bad it’s become. The pathetic quadrumvirate of current leaders of the US Empire show this particularly starkly:

- We have Blinken, the military leader: “The world doesn’t organize itself. When we’re not engaged, when we don’t lead, then one of two things happens: either some other country tries to take our place, but probably not in a way that advances our interests and values, or no one does, and then you get chaos.”

- We have Yellen, the financial leader: “Unemployment serves as a worker-discipline device because the prospect of a costly unemployment spell produces sufficient fear of job loss.”

- We have Nuland, the ‘foreign policy’ leader, organizing reckless, murderous coups all over the world and calling for all-out armageddon-level wars against Russia and China. And saying: “Fuck the EU.”

- And we have Warmonger-in-Chief Biden: “American leadership is what holds the world together”. Uh huh.

It would be hard to imagine a less competent group of people to have in power. You could pick four people off the streets and put them in power and they would almost certainly be less-awful fuck-ups than this gang of clowns.

I’m not sure Aurélien ‘blames’ anyone or anything for this dearth of competence. There are times when he seems to acknowledge that we’re all doing our best (which is what I, really, honestly, believe, sad to say), and other times when he seems ready to blame the education system, or a powerful-but-unorganized group he calls the Professional-Managerial Caste (PMC), or just character flaws among those in power.

But whether or not anyone is responsible, he says the result is the tendency of those in power, realizing that, perhaps due to widespread incompetence or system sclerosis or system collapse or some combination thereof, they cannot really accomplish anything, to substitute talk for action.

He calls this “performative behaviour”. So, for example, since Bernie Sanders knows he will never be allowed by the Democratic Party establishment to do any of the things he knows needs to be done (like instituting universal free health care, or opposing the Israeli-American genocide in Palestine), he has to settle for expressing his strong opinions on these subjects “in no uncertain terms”.

The Democratic Party establishment is delighted for him to do so. His speeches keep some hopeful leftists in the Democratic tent a little longer, while actually accomplishing nothing whatsoever, least of all affecting government policies and actions.

Devoid of the capacity and competence to actually get anything done (and hence to promise to do something, lest you be called on it later), our ‘leaders’ are content instead to issue what Aurélien calls “statements of what they Are [or Think, or Believe], not what they are [actually] doing or intend to Do”. Or even worse, statements that merely say what or who they are opposed to.

I guess when you never actually do anything, it’s hard to be accused of doing anything wrong. You just stand up there with the flag behind you, and an appropriately culturally diverse group of people smiling at your side, and tell the world what you Believe. (And then have the press corps scribes ready to repeat your statement as truth and ‘action’, in all the major media and through your bots in the social media.)

Whole parties and movements are now merely based on proclamations of what the group believes or how it identifies itself, or what it thinks “needs to be done”, or “must be done”, or “must be opposed” or “must be stopped”. Who is supposed to do it or stop it, and how, is usually left conveniently unstated. Or there’s always the fall-back to the not-so-royal “we”, as in “We all must now…” No actual action is required, other than group gatherings to make the rhetorical proclamations, loudly and righteously, over and over.

As I have said repeatedly: This is what collapse looks like. One can imagine the last leaders of the Roman Empire urging the masses with speeches from the rooftops and ramparts to “Make Rome Great Again!”

In short, what we have seen over the past century, as all of civilization’s systems have become more and more complex and unmanageable, is an unrelenting, uninterrupted, 100-year-long succession of failures in all our systems and institutions. The utter failure of all of the many recent wars engineered by the US Empire to accomplish anything is the obvious example.

The staggering incompetence of our handling of the CoVid-19 pandemic, which we knew was coming, and which nevertheless our broken systems enabled millions of people to die horrible, unnecessary deaths, is just kind of the icing on the incompetence cake. Whether or not the public health systems were already so broken that those millions would have died even if the system leaders were competent, is pretty much a moot point.

There is IMO no one to ‘blame’ for this, and I sense that our absurd and incompetent leaders are now mostly just pretending (even to themselves) that these collapsing systems — overburdened by unsustainable debts, desolated ecosystems, exhausted resources, and insane overpopulation of the species, among other things — can somehow respond to their bidding when they are irreparably broken. Our ‘leaders’ (especially Trump, the epitome of incompetence) are like King Canute, ordering back the waves*.

So now the citizens have largely given up belief that our systems and institutions are incapable of doing anything competently, leading to a nostalgic and deluded view among conservatives that things were better in the rugged individualist old days when it was every man for himself (pioneers), when adults were competent at doing everything needed to survive and thrive (hard-working men in patriarchal families), when good guys fought evil (cowboys, vigilantes), when the responsibility was on you yourself to succeed (rags-to-riches stories), and to heal yourself (religions, self-help), when you learned what you needed from your parents or on the streets, when geniuses single-handedly invented miraculous world-changing technologies (Franklin, Ford). And the same nostalgia prevails among leftists about the dashed promises of progress, innovation, the American Dream, socialism, anarchism, working-class revolution, left-libertarian communitarianism, etc.

So we see many new right-wing governments trying to turn back the clock to fictitious past days of glory, order and self-discipline. And the left, unable to sell nostalgia to their slightly-smarter supporters, and devoid of any new answers, is in broad and chaotic, self-blame-y retreat.

This substituting belief and speech for action may be partly due to laziness, or fear of consequences, but mostly I think it’s the awareness that when systems are falling apart, they become dysfunctional and sclerotic to the point it actually becomes impossible to do anything other than what the system in place is already doing. (You know, like launching endless wars, and tinkering with interest rates.) When no one can actually change or fix the system, politicians mostly differentiate themselves on the basis of what they might ideally like to do in accordance with their beliefs, but cannot. Though of course they won’t admit their incapacity, or their incompetence, to their supporters. Hope, anyone?

So now, the game is just playing itself out, with the systems, designed to resist change, so entrenched and inflexible and broken that even with near-universal agreement we cannot do something as simple as reversing the error of Daylight Saving Time.

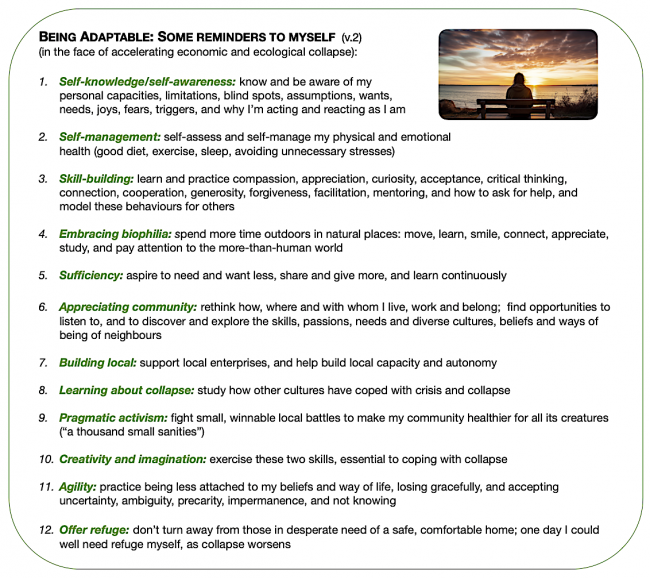

It’s all coming down, and nothing — not appeal to the Rapture, not nostalgia for the good old days when things were simpler and better, not new technology or better morals or magical humanist thinking — is going to stop it. All we can do is chronicle it and do what we can do to cope as it all falls apart, slowly and then all at once.

* Yes, I’m aware that most scholars believe Canute was actually merely pointing out to his followers the limitations of human, even royal, power, compared to that of nature (God).