In praise of the vernacular.

photo of Ivan Illich (2nd left) and Gustavo Esteva (2nd right), from Radical Ecological Democracy

The idea of ‘practicing’ how we might live in the societies that emerge after civilization’s collapse has always interested me. I’m convinced that we’re not likely going to be able to create viable models of new ways to live, at least not at any scale, until our current global industrial civilization culture has collapsed and ‘gotten out of the way’. But why not practice now anyway, and learn a thing or two in the process?

This is what underlies my fascination with Intentional Communities, which are, in many cases, attempts to do just that — to find a more resilient, sustainable, humane, peaceful and connected way to live and make a living together than the ones on offer from our global industrial civilization. While there are some remarkable, enduring exceptions, most of these ‘model communities’ rarely last. The reasons for that are complicated and varied (loss of founders, financial problems, unreasonable expectations, inequitable workload, dysfunctional members etc.)

In any case, it’s unlikely that anything we learn now will be of much use to post-civilization societies when they emerge — in a generation, a century, or even a millennium from now. And it’s far from certain our species will survive at all. Still, there’s no harm thinking about what models might work, and, perhaps more importantly, about the factors that distinguish those that work from those that don’t.

There are two dangerous tendencies among those who like to think about creating alternative models of how humans ‘should’ live — (i) the tendency to idealize, and invent a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model that fits with one’s personal (often impracticable) ideals and parochial worldview, and (ii) the tendency to think that any effective community model can be ‘designed’ top-down, rather than it just emerging and evolving, through the collective efforts of its participants, to meet uniquely local, ‘vernacular’ needs.

As an incorrigible idealist myself, I confess that, especially in its early years, this blog was replete with idealistic models of better ways to live and be in the world, which are now mostly cringe-worthy. I refuse to take them down because they remind me of past errors in my thinking, and hopefully prevent me from making the same errors again.

And as an impatient person who loves to design things, I confess I have often thought I ‘knew better’ what needed to be done in a particular situation than the people actually personally steeped in the problem. I have often later apologized for my hubris.

I preface this article with those caveats because two of the people who tried valiantly to develop alternative models to the capitalistic crypto-democratic hierarchical massive-scale globalized systems we are struggling with today (and watching fall apart) were staunch, almost rabid, idealists. They were Ivan Illich (1926-2002) and Gustavo Esteva (1936-2022 — a victim of CoVid-19).

What I appreciated about these two, who knew each other well and worked together in some of the most impoverished parts of México, is that they had the courage to try to implement their vision and model of a better way to live in the communities they were adopted into and grew to love. Nothing like a dose of practical reality to take the polished edge off your idealism.

Both of them had seen (mostly from the work of religious missionaries) the carnage that results from attempts to impose an ideology (religious, political, or economic), and even impose a way of being, on an entire population. Instead, as Ivan put it, it’s essential to understand and embrace the vernacular — the ways that have emerged and evolved in each local place to suit their unique circumstances and cultures, ways that “made poverty tolerable” there.

Ivan focused much of his attention on two rigid, imposed European-model systems — education and ‘health care’. The alternative, community-based, community-responsive systems he strove to implement were ‘convivial’ — based on local knowledge and local connection, and on the development of demonstrated competencies, not academic degrees.

He fiercely defended his uncompromising ideals — including that the precondition for creating more responsive, effective, local communities and competencies was the complete abolition of the existing systems. He intuitively understood that radical change was not possible as long as the existing systems, dysfunctional as they were, remained in place, with their inevitably invested, change-resistant, staunch defenders.

He described the ‘health care system’ as inherently iatrogenic — causing and increasing disease rather than reducing it — and favoured systems that empowered the ‘patient’ citizen to learn enough to self-diagnose and self-treat many illnesses, to prevent rather than treat illnesses, and to work as a partner with community health care practitioners instead of waiting for the practitioners to just tell them what was wrong and what to do.

His colleague Gustavo worked closely with the Zapatistas to support their efforts to create a revolutionary, autonomous state free from Méxican government interference and ‘help’. He established the anti-authoritarian unschooling Universidad de la Tierra and spent his life working against the “hegemony” of both nation-states and corporate oligopolies, which he saw as dysfunctional institutions that needed to be abolished. A better alternative, he insisted, would come from indigenous communities themselves, developing local solutions that they would then share with other communities. The educational, political, economic, health care and other systems being forced on nations all over the world had never worked for the benefit of the citizens, he said, nor could they be reformed. They needed to be replaced.

Both men were extremely outspoken, often controversial, and not always particularly liked. They both intuitively loathed institutions and institutional ‘solutions’, believing that they were inflexible, incapable of evolving and learning, and that they incapacitated citizens from learning to do things for themselves. Even fans and positive reviewers of their work often criticized much of what they said for “going too far”.

Here’s my brief summary of what I thought were the main points from two of Ivan’s best-known books, with some excerpts of his principal ideas. And here’s an article by Gustavo explaining his “path to freedom” for communities. They’ll give you a bit of a flavour for their beliefs and approaches in their own words.

What are the shared principles that underlie small-scale, autonomous ‘vernacular’ systems that have emerged and evolved in indigenous communities and enabled their citizens to thrive? I don’t know that they have ever been specifically articulated, but I thought I would try to identify some of them. There is probably no ‘process’ that could necessarily nurture this emergence; like most natural systems, it’s a matter of trial and error, and learning and evolving by doing. Here’s what I came up with (it’s far from complete):

The emergence of effective ways to be in community requires:

- That the members of the community learn and practice the ‘convivial’ arts of listening, conversation, collaboration, consensus building, critical thinking, conflict resolution, self-management, and self-directed learning — a curiosity-driven ‘learning how to learn’ for oneself instead of having to be ‘taught’.

- A deep understanding and appreciation of the local land and its inhabitants, all the forms of life including humans who ‘belong’ to the land; and hence what the land and its inhabitants offer, and what they need, and a continuous effort to sustainably draw on (accept, gift, harvest) what they offer and to meet their needs, cooperatively. And an ethic that enables everyone to appreciate when the interests of the community outweigh personal interests.

- Constant opportunities to learn and practice new capacities, both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’, to hone these capacities through working with self-selected mentors, watching demonstrations, apprenticing, and through doing and learning from facilitated practice and from mistakes, rather than ‘schooling’ or textbook-based ‘instruction’. And from play! [I saw this learning-from-demonstrations-and-apprenticing ably demonstrated during my short visit with Joe Bageant in a small village in Belize many years ago.]

- Nurturing the capacity in each of us to take care of our own and others’ health and well-being, including preventative actions (such as a good diet and exercise and accident prevention), self-diagnostic and self-treatment capacities, and understanding what constitutes a ‘good death’. And it requires ensuring that every child achieves the sense of secure attachment and the capacity to be authentic and true to him- or herself, free from abuse, that are needed to grow up to be a healthy, competent, non-dependent adult within a healthy, competent, self-sufficient community.

- The nurturing of opportunities to give vent to our passions to create and express ourselves through the arts, and to explore, and to discover.

- A capacity to create lasting confederations with other nearby communities, each respecting each other’s autonomy and unique ways, but also supporting each other in facing shared challenges.

- The creation of structures (eg for housing and transportation) that maximize conviviality and connection, and minimize isolation.

- An appreciation of the need to keep the community small, resilient, autonomous, adaptable, and in balance with the rest of life on the land (ie the objective is never ‘growth’).

- In all of the above, a continuing collective self-assessment of how the community is doing in each of these areas, and a collective determination of remedial actions when necessary.

There are probably many other requirements that a post-civ community will have to accommodate to thrive when our species starts over (probably again and again) after civilization’s collapse, to learn how to live as part of and in concert with all-life-on-earth. Thinking about what I have observed and read about wild creatures, it seems to me they mostly have these capacities, remarkably without the need for language to acquire or sustain them.

We also surely have much to learn from indigenous communities and those who have lived in them, though I suspect that, because their cultures have been so diminished by the destruction of their ways of life by our industrial civilization, that wisdom is quickly being lost.

I think Ivan and Gustavo, were they to look at the above list, would say that these were some of the qualities they spent their lives trying to help the communities they worked with, to achieve.

So this is not a model, a prescription, a process, a recipe, or even a set of ingredients for a functional community. It’s really, I think, just a list of preconditions for any successful human culture. Almost none of these preconditions are present, I would say, in most of our current cultures, or at least our western cultures. There is no prescription for how these preconditions might or could or should be met; they are emergent properties, not something that can be planned for or imposed. We will learn to meet them when we have to — or not. And most of that learning will likely have to await the collapse of the existing systems that consume almost all of our time and attention, and which fiercely resist such alternative ways of being and doing.

In reading this list, though, the joyful pessimist in me believes that some day in the long distant future there could well be many flourishing (probably largely tribal) human societies that meet these preconditions. Much will depend, I think, on our capacity to deal with the affliction of our species’ large brains and the separate, fearful selves they have concocted, inventions that, I suspect, make creating and sustaining cohesive communities so much harder than it has to be.

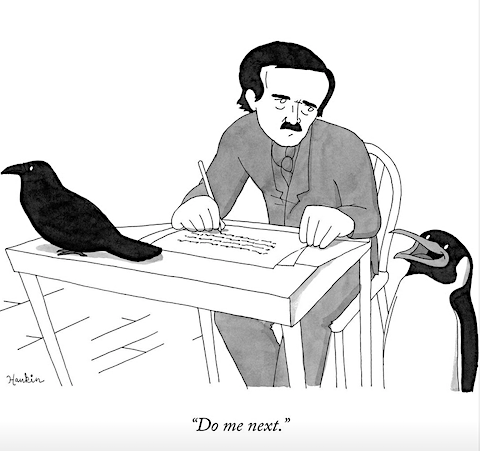

Me, I just watch the local community of crows out my window, with wonder and awe. They obviously meet all these preconditions and do all these things, in spades.

Y’know, what healthy creatures do.