Problem perception before (green) and after (red) people are conditioned to learned helplessness. One of my most popular articles was a review of Malcolm Gladwell’s article on SUVs, which concluded that we are afraid of, and worried by, the wrong things, that, for example, we are needlessly fearful of terrorist attacks and not nearly fearful enough about drunk driving. The consequence of this is dysfunctional behaviour: For example, we buy SUVs, rely on their illusory invulnerability and drive them overconfidently to the point that we actually run a greater risk of death or serious injury in an SUV than we would in a convertible. Yet “the risks posed to life and limb by forces outside our control are dwarfed by the factors we can control”, Gladwell concludes. “Our fixation with helplessness distorts our perceptions of risk.” In that article, I pushed Gladwell’s argument further, and said: This delusion of danger, and the illusion that something can or has to be done, that someone — British cows, Canadian farmers, Firestone, Saddam Hussein — must be brought to account in order to give us back control, is literally making us all crazy. It causes us to believe we cannot let children out of our sight even for a moment. It causes us to wildly change our diets, to avoid visiting whole countries, to fingerprint whole nations of visitors, to suspend civil liberties, to put barbed wire around our communities, to drink only bottled water, to introduce five levels of increasingly hysterical ‘threat’ to everyone’s safety.

It is irrational, neurotic, panic-stricken behaviour, a wild over-reaction to a tiny uncontrollable risk while we recklessly disregard risks we could control and which kill and destroy lives in large numbers everyday — air and water pollution, tainted food from corrupt and underregulated meat packers, drugs in sport and airplane cockpits, drunk drivers, kids with guns, unsupervised swimming pools, corporate frauds, a prison system that incarcerates the mentally ill and encourages criminal recidivism — and on and on and on.

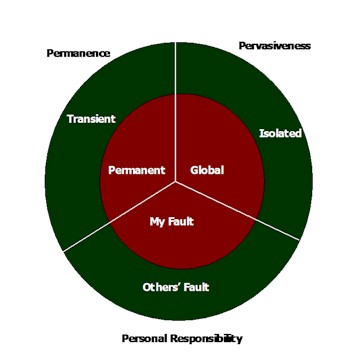

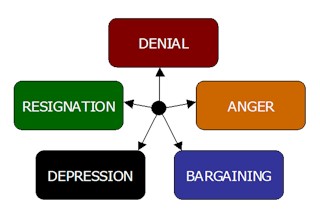

Unfortunately, it is also in the best interest of the media and governments to focus on the uncontrollable risks, and to pander to public fear and fascination with them. They’re more sensational, more visceral. And since there’s really nothing that can be done about them, you can do anything, or nothing, in response to them, and not be held accountable, or responsible. The risks we could control, on the other hand, are mundane, day-to-day, hard and expensive but not impossible to remedy; they would if remedied save thousands of lives, and are the responsibility of all of us. Viewers, voters, and consumers don’t like to think about such things. Messy. Complicated. Nagging. Costly. And the media, and politicians, are glad to oblige us. The concept of learned helplessness originated with Martin Seligman, whose research forty years ago (involving the psychological torture of dogs) revealed that we can be conditioned to fear things and to believe we are helpless to deal with them. What he called the “three Ps”, illustrated in the diagram above, determine the extent of this resultant psychosis — we can be conditioned to blame ourselves instead of others for a problem, to see a transient threat as a permanent one, and to see a local, isolated threat as a pervasive one. In fabricating an excuse to strip Americans of their civil liberties, for example, Bush, with media compliance, inflated the threat of terrorist attacks in the minds of Americans from a symbolic attack on two American monuments to a ubiquitous, permanent and pervasive threat to every American by a massive, globally coordinated and maniacal army supported by conveniently-selected Arab states. And by telling us to ‘be extremely vigilant’, to treat those who opposed his draconian measures as traitors, to be suspicious of any activity by those with swarthy complexions, and to equip ourselves with duct tape, Bush implied that if we were the next victims of this hyperinflated enemy, it would be to some extent our own fault. Thus, a transient, isolated publicity stunt by a small group of rich psychopaths, caused principally by a clash of cultural ideals and bolstered by regional poverty and suffering, was turned for cynical political reasons into a permanent, pervasive war that (“if you’re not with us, you’re with the terrorists”) we would be largely to blame for if we didn’t blindly support our government. Once inculcated with learned helplessness, its effects on a person can be quite perverse. When something bad happens (e.g. he/she loses his/her job to offshoring) that person will tend to blame him/herself, to be overwhelmed by the seeming hopelessness of resolving the problem (“there are no other jobs”) and to see its effect as permanent (“now I’ll be unemployed for life”). Paradoxically, when something good happens (e.g. they get a promotion), this same person will not tend to credit him/herself (“I was just lucky”), and will see its effects as isolated and temporary (“I’ll never get another promotion, and I’ll probably screw this one up and get fired”). To psychologists, these are irrational symptoms of a pessimistic, depression-prone personality. Those vulnerable to learned helplessness conditioning are also, they would seem to be saying, vulnerable to depression. Depression is one of five bad news coping mechanisms I referred to in a previous article. The other four are denial (“I can’t believe I lost my job, there must be some mistake”), anger/selfishness (“I got shafted, the boss is an idiot”), bargaining/pragmatism (“maybe I can get it back”) and resignation/acceptance (“oh, well, time to try something else”). Those who write about these coping mechanisms tend to view the fifth as being the ‘mature’ mechanism, but that’s subjective — maybe the boss is an idiot, or maybe you can get the job back.

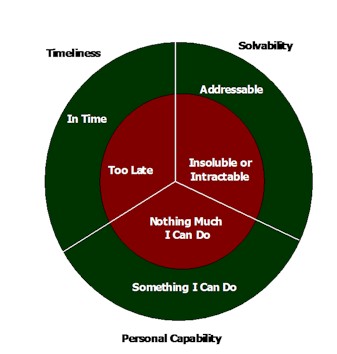

Once you’ve reacted to a situation, the mechanism you use for resolving the situation tends to reflect the same mentality (afflicted with learned helplessness, or not) that manifested itself in the reaction, as the figure below illustrates. Those suffering from learned helplessness tend to believe there is nothing much they can do, that the problem is insoluble or intractable, and that it’s too late to act.

Seligman has now moved on from unpleasant experiments on dogs to a self-help movement called Authentic Happiness, which is based on his concept of learned optimism, the flip-side of learned helplessness. I don’t think much of it, but then I’m not taken with any self-help or psychological ‘solutions’. I believe things happen the way they do for a reason, and rather than trying to ‘cure’ depression maybe we need to understand why it is so endemic to our modern world. Is depression like the ‘shutting down’ coping reaction of animals cornered by predators? And is the power elite actually cynically encouraging this sense of ‘learned helplessness’ because it lowers opposition to the status quo, and stifles dissent, even though this elite actually has a lot less power than any of us believe? It is quite conceivable to me that most people (who are not blog readers, or readers of much of anything of quality) reasonably believe nothing they do makes much real difference, and hence they would not find any news they read actionable anyway. They live day to day, moment to moment, and their decisions are mundane (McDonalds or Burger King). I think they are relatively immune to media spin, but very vulnerable to influence from their immediate communities — neighbours, family members, co-workers, churchmembers etc. They move in crowds, physically, emotionally, intellectually. Belatedly, they were the mass that finally ended the Vietnam War and brought down Nixon, and they are the mass that re-elected both Clinton and Bush because change frightens them more than the status quo. But is their sense of impotence and their passivity in the face of all the challenges facing the world today:

Let’s take a look at the environmental movement, for example. I have described what I call ‘light green’ environmentalists, who are optimistic that technology and social awareness will let us resolve the current environmental crises, and ‘dark green’ environmentalists, who are pessimistic sometimes to the point they actually look forward to the end of civilization. The former see the latter as depressed or angry, while the latter see the former as bargaining or in denial. Like liberals and conservatives, they see the same dilemma through irreconcilably different frames, but their core values are the same: They realize, instinctively, emotionally and intellectually, that the only way for the human species to go on is as an integral part of all life on Earth, connected, in balance, living sustainably. They just have different visions of how to get there, and a different sense, not of how much we can do, but of what we should do. Lots of theories here. What do I believe? Well, I keep thinking about Einstein’s remark, shortly before he died, that it was his experience that the more people knew, the more pessimistic they became. And since I believe most people, for a variety of reasons, know very little about the state of the world and what can be done about it, I’m inclined to believe that many people are pessimistic, not due to learned helplessness, but because they ‘know’ instinctively that the world is facing some massive challenges, that short of a revolution (which few are prepared to precipitate, at least not yet) there is genuinely little they can do to help address these challenges. I think the influence of media ‘spin’ on this perception is minor. And I believe that many people are instinctively coming to realize that no one, no elite, is in control of this world (if any ever was), and that therefore even a revolution would be futile (as indeed most political revolutions in history have been). I think we have a lot to learn about minor things (like the foolishness of feeling safe in an SUV, and the foolishness of feeling insecure about our child’s safety unless we know exactly where they are every instant), and in these things we are prone to misjudgements both of learned helplessness and of learned (over)optimism. But when it comes to the bigger issues affecting the future of our world, I believe our instincts are pretty good. Perhaps the sense that it’s too late to solve these larger issues, that they are perhaps insoluble, and that there’s nothing we can do individually or through some kind of fantasy ‘collective intelligence’ to save civilization, is not learned helplessness, but rather powerful intuition and collective wisdom. And perhaps those of us with the best instincts (mostly, in my experience, women, poets, scientists and artists) have also realized that this resignation does not need to depress us, or debilitate us. On the contrary, it liberates us from the responsibility to ‘save the world’ and refocuses us, our sense of purpose, on making the world better here, now, for those we live with and love, in the communities that define us. Those enlightened people — the women, poets, scientists and artists — have always been focused on opening possibilities here and now, in the moment, in the communities of which they have always known they are a part. They — and not the self-help gurus and others who would ‘cure’ us of our sense of helplessness and depression, not the politicians and revolutionaries and religious and political and technological salvationists and ‘leaders’, not the media analysts and apologists — are our true models, the ones who quietly, always, have been showing us the way. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

this resignation does not need to depress us, or debilitate us. On the contrary, it liberates us from the responsibility to ‘save the world’ and refocuses us, our sense of purpose, on making the world better here, now, for those we live with and love, in the communities that define us. Well said and I completely agree with this. Or take a saintly example like Mother Teresa, I’m not sure of the reunciation part, but this is essentially what she did. Have you heard the statement “be in the world but not of it”?

“women, poets, scientists and artists”First of all: -*ALL* women?-“Artists” – What is the definition of an artist in this meaning? I know many business-people whom I would consider to be artists in the manner that they produce amazing and creative products for society. Same goes for sales-people,marketing-people, etc.

I’m inclined to believe that many people are pessimistic, not due to learned helplessness, but because they ‘know’ instinctively that the world is facing some massive challenges, that short of a revolution (which few are prepared to precipitate, at least not yet) there is genuinely little they can do to help address these challenges. I think the influence of media ‘spin’ on this perception is minor.And I believe that many people are instinctively coming to realize that no one, no elite, is in control of this world (if any ever was), and that therefore even a revolution would be futile (as indeed most political revolutions in history have been). This is me, most of the time .. and as I dislike believing that I have fallen into learned helplessness, what I do is (as I think I have said before) try to be helpful to others, work at being a good friend, live within my means, use strategies that minimize my entanglement with a system I believe little in, do no harm as much as possible, and try to find ways to speak out and get the few humans I come into contact with to question authority, amd challenge the status quo (or status qui ;-)

so… if no one is going to take on the responsibility of “saving the world” how is it going to get done? While I definitely agree that we should focus on improving the here and now, I think that only focusing on that aspect is kind of like a treatment instead of fixing the cause. It will reduce suffering now, but will fail to prevent suffering in the future. In situations like this, it’s best to take a dual focused approach. 1) treat the current symptoms. 2) treat the actual problem.It’s clear how to treat the symptoms. In order to treat the actual problem though, society needs to be restructured in order to promote healthy behavior in humans. Somehow there has to be active control of our future, or else our society will continue to be helpless just like its people are. People don’t just become adults by turning 18 or by graduating. Adulthood is a defined by maturity and the acceptance of responsibility for ones actions and how they affect ourselves and other both in the present and in the future. At some point in time our society will have to “grow up” and accept responsibility for our actions. We have to plan for our futures to ensure that we aren’t just settling for what is given to us.It seems to me that you are thinking in a very feminine manner, in that you are accepting your fate passively and that you are only capable of a small amount of influence and only on a local scale (for most people). Survival is optimized (for individuals, couples, communities, societies, etc) when there is a balance between masculinity and femininity. If one is overly dominant over the other than survival is hindered. If masculinity is too prominent, we run headlong into trouble and we are injured or soon deceased. If femininity is too prominent, we become helpless to shaping our future and helpless to defend ourselves against the rigors of the world and each other. We as a society are currently really feminine being controlled by really masculineentities, which is an incredibly bad situation because we aren’t masculine enough to make a difference and the rulers are driving us into oblivion.”Trusting our instincts” is only applicable if we act on them. It is not that hard to understand where all the problems (meaning causes not symptoms) are, the hard part is convincing everyone to actually do something and to know what to do.

Thanks for your comments. Voltron, I was generalizing just to be provocative. Not all women, and certainly some people in business, though my observation is that business keeps pushing them out or ghettoizing them in their organizations.Medaille, I’m talking about shifting focus to the local level, to doing things that can actually be done now, not necessarily shifting focus from problems to symptoms. My resignation is that no one is in control, so top-down ‘solutions’ won’t work, and that there is no clear cause-and-effect in most of the world’s intractable problems, so root cause analysis doesn’t work. By working practically at the community level, we can create working models that, thanks to our exploding connectivity, can virally be spread and take root elsewhere. As Bucky said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” That model, starting small, focused and functional, is capable of enormous influence, probably much more influence than can come from doing something conceptual (like writing a book full of brilliant but not clearly actionable ideas) or political (like getting elected as a Green). We cannot convince others, we can only wait for them to be ready to understand. Telling me that this is thinking in a ‘very feminine manner’ is the nicest compliment I have received since a kind reader called How to Save the World ‘the New Yorker of blogs’.

Dave, a lot of what I read of yours talks a lot about starting from the bottom up. I think that in order to make an impact there has to be a balance between the effectiveness of a extremely local solution and reaching a large enough number of people to reach the critical mass required for other people to understand fully your cause and to influence them to follow your action. I don’t think that one community of 10-25 people is adequate to achieve that, although for your model a network of say 100-200 communities that size would probably be adequate. An extremely important thing (I’m sure you’ve already thought of this) for you to consider when you use connectivity to promote your model is a detailed step by step method of converting their current living arrangement into the new proposed model. I’m confident that there needs to be a single person or small group at the helm to make the changes in the community. This is because it is rare for people to have both the knowledge required and the ability required to make the change, although once critical mass is achieved then it will be significantly easier. I agree that Connectivity will aid in this significantly.With regards to Bucky’s statement, I agree that you can’t fight the existing reality, but I think that to a certain extent that’s exactly what you are doing by focusing on an extremely local level. It allows the existing reality to reinforce undesirable patterns and it will make it harder for each person to convert their method of thinking to the new model, thus it will make it more difficult to sustain the change and more input costs will go into (as Illich states it) therapy to bridge the clash in cultures.I think that it is wise to focus on making small significant changes in infrastructure that promote desirable patterns in the citizens everyday life. This will make it easier to influence people in the proper direction and will remove some of the competing forces that stand in the wayof your goals. I think a community of at least 50,000 is large enough to reach critical mass yet easy enough to change with the proper local influence. Top down solutions are a better method because “you” will be in control until the model is self-sufficient. At the very least the infrastructure and set-up of the society require a guiding hand.As far as cause-and-effect’s relation to the world problems, root cause analysis is irrelevant. What can be determined is the general trend or the push/pull effect of an input or force. If you are alert to the forces at work that influence people than you can change the negative forces into ones that promote desirable patterns. It is not necessary to define the exact causes with complete certainty, but it is necessary to know what the causes are. This could be easily done through statistical analysis with a large enough population size. To explain what I mean, you are looking for how culture (in the sense of how it influences the brains patterns) varies on a local level and how it influences the general trend of the people exposed to it. If there is a strong correlation between people being happier by using mass transportation instead of individual vehicles than it is important to put that in design of the model. If there is a strong correlation between people existing under a “socially darwinistic” capitalistic economy and them making selfish decisions instead of responsible decisions then an effort should be taken to rearrange the infrastructure to promote making responsible decisions. By changing the infrastructure (which is relatively easy as most of it can be accomplished by changing laws or services provided by the local government) you are changing the existing reality to one that makes the overall transition to the new model and new method of thinking/culture that correspondes with it much easier, because you won’t have to fight the old undesirable culture directly.I’m not sure if I made my definition of culture clear enough. Byculture, I don’t mean on a broad level. I’m talking about all of the patterns that the brain learns due to external influence. This could be the wording on posters, or the method used to accomplish something as modeled by another person, or the constant bombardment by advertisements that we must conform to an ideal model which is not our own, or that happiness is achieved through consumption because our society is setup to promote that, etc.

I know you guys largely ignore me but thats ok, I wanted to pipe in anyway about this comment: That model, starting small, focused and functional, is capable of enormous influence, probably much more influence than can come from doing something conceptual (like writing a book full of brilliant but not clearly actionable ideas) or political (like getting elected as a Green). Think Gandhi’s salt march, that took enormouse vision but the action was extremely simple and effective. So vision is necessary and so is effective action, and unless you’re a law maker I can’t think of a way to implement effective action except on a local scale (physically, or in cyberspace I suppose).

Zach: Absolutely. And how nationally, even globally significant Gandhi’s local protest proved to be.Medaille: If one community of 10-25 people is able to influence nine others to do likewise, then I think you have the critical mass to change the whole system bottom-up. It’s just a theory, but seems to resonate with the way diseases spread from a very small point of entry, and how evolutionary changes in nature take hold if they have an advantage over the incumbent ‘model’. The collapse of the Soviet Union was not a top-down change project. The models we choose can tap into the wisdom of crowds, but they will not be monolithic — beyond certain basic principles, I can see a new economy, political system, society and culture playing itself out with a lot of local variation, and these local experiments will refin the model more effectively than top-down ‘guidance’.

Though I see someone mentioned Mother Teresa, we’re missing the one famous quote that sums it all up: “We can do no great things; only small things with great love.”Bravo on those last two paragraphs, Dave. While I agree with medaille that there needs to be balance of the “masculine” and “feminine” – the Taoist yin and yang – in a world largely dominated by the yang, this wise resignation that we can do not “great things” does not resign us to all out hopelessness, though that’s what the prevailing culture has us believe, especially the whole “American new thought movement.” As a Zen practitioner myself, I know that a deep love for the here and now is the only thing that keeps us sane and lets us take wise, mindful action.But, the bottom line is we humans like to take everything way too seriously. Going crazy trying to save the whole world from the top down is not the Taoist way of “effortless living” :)