In a recent article, I provided an overview of Customer Anthropology, one of the hottest research and innovation tools in business today. The essence of this approach is that customers often don’t know what they need, so by spending time observing them using your products (and your competitors’ products) you can often identify many business opportunities (and threats) that sales analysis, interviews and customer satisfaction surveys won’t reveal. If you’re an aspiring entrepreneur, your first important task is to find an unmet need, understand why it is not currently being met, and assess whether you and your partners have the capabilities and resources to meet it. Customer Anthropology provides a terrific means to do this task. It allows you to see, first hand, what people need that isn’t being provided by current products (users cursing, complaining, and working around deficiencies in the existing products is a great clue). And it enables you to see why the current products aren’t meeting the need, which can help you determine why the very smart incumbent producers are missing the mark. Of course, you also need to understand the production economics and the technology limitations, but observing customers will get you off on the right foot. Most of the examples of Customer Anthropology in the literature are business-to-business. Steelcase uses this approach to design effective workspaces for its customers, which are, at least directly, other corporations. Medical technology companies use this approach by visiting hospitals and medical facilities, and they’re observing the doctors and staff, not the patients. Once corporate customers appreciate the benefits of Customer Anthropology, they’re often more than willing to allow their suppliers to observe their people at work. And they’re curious to learn about how to use the technique with their customers. But what do you do when your customer is the public, or when, although you may sell your product through intermediaries, it is the public’s use and satisfaction with the product you want to observe, not the intermediary’s? In one sense, because you don’t need to get permission to access corporate offices, Customer Anthropology with the public is easier than with corporate customers. But there are a number of issues to address:

Let’s take each of these issues in turn. Respecting Privacy On the privacy issue, it’s important that you be honest and open with those you are observing, even though to some degree that may compromise the accuracy of your observations. If the customer knows you are observing them using their product, they’re less likely to throw it across the room in frustration. This is an issue that anthropologists deal with all the time. They need to gain the trust of the people they are observing. That trust requires absolute honesty. If they’re using your product (or a product similar to something you’re thinking of producing) for dubious purposes, or if they’re awkward using it, they need to know you won’t rat them out or ridicule them. They need to know you’re observing them solely to help you design a better product for them to use, and they need to have given their consent to be observed. And you, as the anthropologist, need to have the judgement skills to know when what you’re observing is bona fide behaviour, and when it’s a performance for your benefit. As observer, you need to make yourself as inconspicuous as possible. If the use of the product you’re studying occurs in public places, you can of course do some observation without the knowledge or consent of the people you’re observing. But there are serious limits to such opportunities. One of the key elements of Customer Anthropology is the follow-up interview with those you’re observing to clarify behaviours that you didn’t understand simply from watching. You can’t go up to a stranger and say “I’ve been observing you trying to use that cigarette lighter to start your barbecue. Can I ask you a few questions about why you’re doing that?” It can be useful, if you can afford it, to offer some incentives to those you are observing, to encourage them to allow you to let you eavesdrop on them. The Nielsen company did this for years to get the right to monitor exactly what parts of what programs and commercials customers were watching on TV. The customer got various gifts and monetary rewards, and Nielsen got the unvarnished truth, which turned out to be a lot different from what people said they were and weren’t watching in surveys. One of the cleverest incentives I’ve heard of was providing the customers under observation with digital cameras or even movie cameras, and inviting the customers to use the cameras to film themselves and their friends using the product in question (I believe it was a sports shoe). That way, the observer and the observation were less obtrusive, and the customer got to use the cameras for other, personal purposes during the observation period, and to keep the resultant footage. The possibilities for getting around the privacy issue and getting cooperation from those you are observing are limited only by your imagination (and your research budget). Gaining Access Suppose you’re a great admirer of Interface Carpets (full disclosure: I’m a great admirer, and I have a few shares in this company). You like the fact that they make cradle-to-cradle carpet products (no virgin material, everything 100% recycled) for the industrial/commercial market, but feel that there is a need for something similar but customized to the residential market. One of the advantages of the Interface model is that their carpet comes in 1′ square pieces, like tile, so that the carpet in areas of heavy wear and with unremovable stains can be replaced without having to replace the entire carpet. You want to see if this model might work in private homes, but how to get inside? Do people still buy carpet for their homes, or is everyone going to hardwood, composites and tile? You might settle for just visiting the homes of people you know. You might hang out at carpet stores and eavesdrop until you wore out your welcome. You might buy data from an insurance company on what percentage of residential floors have each different kind of flooring (they do compile this data). Now, use a bit more imagination. Who sees the carpet in thousands of people’s homes? Carpet and flooring installers. So you might offer some incentive to an installer to do your observation for you. Even better, you might volunteer to ‘apprentice’ with an installer for free for a couple of months on a part-time basis — the first day on each new job. You help with the grunt work — removing the old carpet, carrying in the supplies etc., and in return you get to gather first-hand information about all the flooring in the homes of people who are replacing their existing flooring — precisely your potential customers. And as ‘apprentice’ you can chat with the homeowner and the installer and ask some questions to feel out the market for your idea. Defining Your ‘Customers’ Here’s where the need/affinity matrix pictured above comes in. There are three steps to sussing out unmet needs to fill:

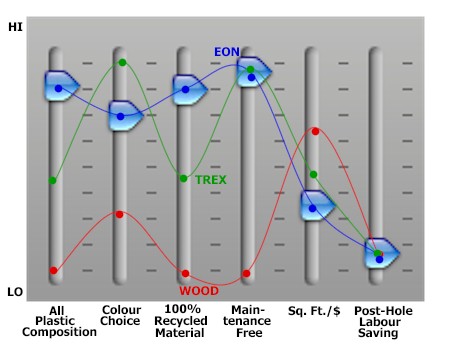

This is a complex process, and one that is often poorly done by researchers and marketers and designers and advertisers who try to reduce this to a merely complicated process. They’re content to know the ‘demographics’ of their users, a very rough cut at segmenting the market for a product. But such demographics leave out or bury the most valuable information, information on why certain groups have this need. Market surveys are inadequate to unearth this information, or even to identify the precise affinity groups that share a particular need. They don’t fit within the parameters of simple/complicated ‘choose one answer’ survey questions. Observation and one-on-one interviews provide a much richer mine of information about needs. Since your brain, unlike surveys, is capable of embracing complexity, interpreting Customer Anthropology and follow-up interview data can allow you to put together a much more precise need/affinity matrix than most of the big players in any industry would have either the ability or the patience for (what may be a very comfortable and lucrative niche for your business is likely too small and too risky for big competitors stretching for huge, high-margin growth every year). The graphic above shows an example of this process, the plastic decking (like Eon or Trex) and fencing materials that are eating into the market of outdoor wood decks and wood and metal fences. A number of years ago, some enterprising individuals identified several unmet needs in this area: Outdoor decks and fences that didn’t need a lot of regular maintenance (painting and repair), were relatively simple to install, and did not use creosote or other preservatives shown to be hazardous to health. The ‘job to be done’ was a safe (to human health) surface for summer recreation or privacy fence that would last a lifetime with no maintenance. None of the existing wood products did this precise job. Two companies in particular, Eon (a 100% recycled plastic product) and Trex (a recycled plastic/wood composite product), developed products that did this job. They succeeded where others failed because they accurately assessed not only what the ‘job to be done’ was that existing products didn’t do, but precisely who needed that ‘job to be done’ and why. The buying affinity groups weren’t defined by traditional demographics but by (a) their concern for health and safety of their personal recreation and entertainment area (and, to some extent, for the environment) and (b) their lack of time and/or skill for carpentry work. These products were designed, developed and marketed to these specific affinity groups, not to the traditional home-handyman types, as their successful differential strategy canvases, shown below, demonstrates: As an entrepreneur, deciding which of the millions of potential customers to observe is part of the iterative process of finding the sweet spot where you and your entrepreneurial partners’ talents and passions (your Collective Genius) intersects with what there is an unmet need for. The trick is not getting so enamoured with what your Collective Genius could produce that you don’t ensure there is a real, unmet need for it. And not getting so enthusiastic about finding a solution for a real, unmet need you have uncovered through your research and observation that you end up trying to do something outside your Collective Genius (something you’re not especially good at, or which you don’t really relish the thought of spending a lot of your waking hours doing). Trust your instincts to know who might have needs that your Collective Genius could address, and therefore who to observe and interview. Trust your instincts, too, to know when your Customer Anthropology is not working, and to try something, or someone, else. And always pay attention: Good anthropologists don’t turn off their observational and listening skills when they go home at night. Some of the world’s greatest ideas have been serendipitous. And, as I keep emphasizing, I think it’s essential that you not try to do this alone. Collectively you have a lot more Genius than any one person alone can muster. Collectively you have different passions, that allow you and each of your partners to do exclusively what they love. And between you, you have a lot more eyes and ears to observe and research what is needed, and to assess those observations and that researchobjectively. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites