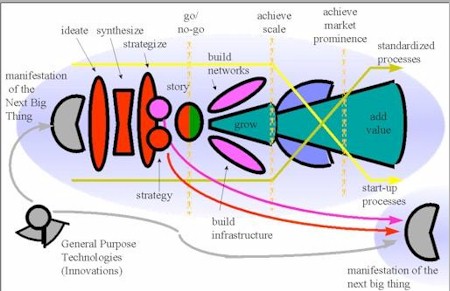

(Innovation & Technology commercialization process, from Credit Suisse First Boston New Economy Forum 1999 Synthesis) In his celebrated book The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clay Christensen explains how successful companies can be “held captive” by their customers to the point that they become vulnerable to disruptive innovation from competitors and new entrants, and unable to sustain the types of innovation that brought them those loyal customers in the first place. He’s absolutely correct, but there are a set of business dilemmas around innovation that are even more profound, pervasive, and cultural entrenched. It is only when you get past the heady idealism of innovation (“the entrepreneur’s competitive advantage”) that the gravity of these dilemmas becomes apparent, and the reasons for the current dearth of innovation in our society become clear. Things happen the way they do for a reason. There are thousands of writers, consultants, business advisors and social reformers out there calling for more innovation as the means of improving organizational performance, productivity and resilience, and achieving breakthroughs in how we tackle social, political, educational, health, economic and environmental problems. They say we need to learn to be better innovators, hire more innovative people, employ more innovative processes and tools, and they’ll tell us how to do it. But somehow, when you look past the hype, this is mostly wishful thinking: There is astonishingly little true innovation happening anywhere in our society, or in business. The more I study this, the more I work with entrepreneurs and the more I think about it, the more I realize there are three, terribly discouraging reasons for this, reasons that have more to do with our modern human culture than economics, marketing or any conspiracy of the established anti-innovation corpocracy. Before I summarize these three reasons I will predict that this article will provoke a minor storm of protest. It goes totally against conventional wisdom and the current wave of popular, euphoric thinking about the untapped potential of innovation. Unlike Christensen’s Dilemma, there are no ready solutions for these three Dilemmas — and people don’t like to hear about problems with no ready solutions. These Dilemmas suggest that innovation consulting and innovation change programs may be largely a waste of time, energy and money. I will probably be accused of being a defeatist, of sour grapes (because I’m not as successful as Christensen and the innovation-touters) or of being discouraging at precisely the time we need to be encouraging organizations to be more innovative. No matter. I just call it as I see it. I’ve seen these Dilemmas played out again and again. I blamed myself for not being able to help my clients and colleagues imagine better, research better, or implement better. I blamed myself for not being able to persuade them that more, bolder innovation was critical to their success, and even their survival, and for not getting them to see the value in imaginative, innovative ideas. But it wasn’t my fault at all. These Dilemmas are insuperable, endemic, and totally engrained in our culture. The three Dilemmas are:

I’m not saying that there aren’t a lot of people who ‘get’ the value proposition for innovation, and are full of good ideas and good intentions. But most of those people are marginalized in our society — they lack the wealth, the connections and the key skills to bring those good ideas to market. And even if they do manage to find some interest for their idea, they are likely to be told that there is no commercial ‘market’ for it, or launch their own business unsuccessfully to find that out for themselves, or have their idea so watered down in the commercialization ‘process’ that it becomes an incremental novelty rather than an innovation. Or, if it’s a really great idea and actually does get close to realization and start to attract buzz, it will be bought out and shut down (or starved of resources, or mismarketed, or unmarketed) by some big corporation who offers the potential entrepreneur an offer she can’t refuse. And since most budding entrepreneurs have none of the skills (and relationships, and self-confidence) needed to start their own business (and no money to acquire those skills in the ‘market’), most great innovative ideas will never get off the drawing board, or even out of the heads of their imaginers. Many solutions have been touted for these Dilemmas (I’ve touted most of them at one point or another): Education is proposed in entrepreneurship, and in imagination, for everyone, starting in high school while it’s ‘free’. Not going to happen — the education system is a poster child for lack of innovation, and has no capacity or incentive to teach these essential skills. ‘Best practices’ in entreprepreneurship and innovation fill the Business shelves of the bookstores, but these (even when they’re honest and not exaggerated to stroke the ego of the author or case study interviewee) are devoid of context, and without a major investment in time and money learning how they apply and how to apply them, they’re useless and often even dangerous to the reader. Governments promise R&D credits, government/university facilities, and other incentives to promote ‘innovation’, but the process for evaluating and operating these programs is so political, bureuacratic and otherwise flawed that the money generally goes to the company that has learned the ‘system’ of writing creative, conforming applications and getting them sponsored by influential people, not to the one that could actually benefit from such programs. Solutions have been proffered to make customers more open to and savvy about innovations, too, but for the most part they haven’t worked either. We all know products that are designed to be simpler and more intuitive are taken up by customers more readily, but designers and developers are so disconnected from customers that they can’t resist adding unneeded, complicating functionality (in response to louder voices inside and outside the organization) that the size of the unfathomable manual ends up exceeding the sixe of the product. And while true innovators focus on ‘must haves’ — real needs — in their design and development, they are usually overruled by marketing and advertising types who find it much easier and more profitable to sell ‘wants’ — to those with so much money that they have no real needs. Customers are so used to being conned by false PR and advertising hype that they don’t believe anything they hear about new products anyway. So, being wary, most follow their neighbours (or kids) in what they buy, rather than buying what it truly innovative. And of course there are lots of foundations and advocacy groups trying to persuade companies and governments to invest in supporting the development of, and subsidizing, products and services that go to those who can’t afford the ‘market’ price. With 90% of all government subsidies and contracts going to a tiny handful of mostly oligopoly companies with deep pockets and politicians at their beck and call, you know how successful most of them have been. They end up spending most of their time competing with other foundations and NFP groups all begging for the dollars of the few tapped-out citizens who care enough to support any altruistic endeavours and the funds of parsinomious government sponsors facing annual double-digit budget cuts. The economy simply and relentlessly mitigates against innovation for those who really need it. As I said at the outset, I see no solutions for these three Dilemmas. I still believe in the innovation process I have been writing about on these pages for the last four years. In an ideal world, this prescription should work. Unfortunately, our world is far from ideal, and perhaps its time for innovation enthusiasts, advocates, consultants and pundits to get real. Our culture, and the economic, political, educational and other systems that support it, are all stacked against true innovation. We need to find a better way, a more practical and realistic way, to bring about the changes that our world so desperately needs. I’m not yet sure what that is, and I’m sure open to suggestions. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Dave – Most of this is true. But it’s so depressing I might as well shoot myself. Obviously we have to start somewhere (or give up). I think the question has to be – where do we start? Who do we start with? And what do we do? I’m going to start by talking to a few people about this. And trying to take on board one innovation a month. Any ones you can recommend for me out here in Australia?

Excellent piece, Dave. Off the top of my head, I can think of three ways to work this issue. (1) We can realize that the current Market Economy is the problem — not the lack of innovation — and work to replace it with a different economic structure like a Gifting Economy that builds new thinking and new neural pathways for we the people. (2) We can stop using the OLD thinking (problem solving), which limits us, and start using the NEW thinking (creative path – see the book “The Path of Least Resistance”) of Unlimited Creativity. (3) We can start RIGHT NOW to build new structures that DO support innovation (see the book “Infinite Wealth” by Barry Carter). Not only does this new infrastructure support innovation, it requires innovation.There is so much we can do, and we can start this very second. We are looking for innovation in the WRONG place — the market economy. Look instead to the recent books like “Digital Aboriginal” and “Free Agent Nation” and “Infinite Wealth” and “For-Giving” and “Unjobbing” and David Korten’s new book, “The Great Turning: from Empire to Earth Community”. It’s happening right now! Those of us on the train to our becoming are excited as hell that we’ve left the Market Economy train to oblivion.It’s so exciting that even the animals feel it. That’s why that sweet birdie was loving on you. Everybody, including the fur people, is waking up to the realization that we are the ONE we’ve been waiting for. So let’s get to it!Blessings,Kay

If we are going to market innovation or work with it and change, we had better get very familiar with the grief cycle. ‘Cause it ain’t resistance to change folks, it’s grieving. Ever tried to get a kid to give up an old toy–“No, i love it…” Is the kid resistant to change…um no…he’s entering the grief cycle (shock and anger. recognize it?) When we can look at it this way, our compassion grows and so does our capacity to think about how we might support each other and our customers in working through this.

Matt, Kay, Wendy: Excellent thinking and ideas. If there’s a way out of this, it’s not analytical, it’s complex-adaptive, it’s collective, and it’s bottom-up, community-based. Small is beautiful, the right scale to accommodate and enable true innovation, and personally responsible, so it evolves innovations responsively instead of supplanting the old with the new, avoiding the wrenching, the lack of consultation with customers, and hence (in more ways than one) the grief.

This conversation is making me think about memes, in an article I read about memes, the author used fashion as an example where the main meme was fashion… the need of expressing changing moods as the main meme, and that it had its offsprings memes (short time memes) as what was chosen as fashion in each changing season. Memes do not need to be positive and prove to be useful, to be wide spread it has to be a good quality meme… For instance it also said that the meme theory itself, had not proof yet to be a good meme, be true or not….. Maybe innovation faces also a meme quality affair.

This post is problematic in both its depth and thoroughness. Unfortunately, so many people are obsessed with “Innovation” as bringing about sexy technology products that they ignore decades of relevant thought leadership on the subject. Read Drucker and accept his basic premises that organizations (for or not-for-profit) exist for only two reasons: marketing and innovation. Paraphrasing Drucker, marketing amounts to finding groups of people with unmet or under-served needs and innovation is an organization’s offering in response. Couched in these terms, it is clear that innovation must be constantly delivered at the strategic, portfolio, and product level. A quick response to your three dilemmas could be:Most entrepreneurs aren’t innovative. Your first statement in this section is instructive, “They got into business to fill a niche that the big companies weren’t interested in.” Recognizing this niche is classic marketing; delivering value to it is classic innovation. Organizations can not start and expect to have any success without doing this at least once. To continue as a going concern, they must replicate this process. Woe is the “entrepreneur” who is a one-trick pony. Sooner or later, they will be a failed business manager.Most customers don’t want innovations. Tell this to the billions of users of Yahoo!, Google, RAZR, iPod, Intel, SAP, post-its, Chipotle, Windows, and the other products and platforms responsible for most of the value created over the past 30 years. Of course consumers can’t ask for elegant new solutions because most don’t think in these terms. There are many levels of Innovation both incremental and game-changing. Organizations should be in the act of considering and implementing both relative to their own size and capabilities. If some specific “Innovation” didn’t catch on, it is by definition NOT an innovation (response to unmeet or under-served needs). Those who need innovations can’t afford them. Again, if they can’t adopt thembecause of cost they aren’t innovations. Consider the past and personal computers. Before cost dropped to make them affordable they weren’t widely adopted. Specific to victims of modern society, Prahalad and others have researched and written extensively about the base of the pyramid and how Western companies have to think and act differently delivering offerings for these markets. Some companies (Hindustan Lever, P&G) are actually generating both customer and shareholder value in this way. Innovation does not happen in a vacuum but instead are a result of user, technological, and business context. I am sorry to so seriously disagree with your thoughts Dave, but I don’t want these “Dilemmas” to provide any force in the backlash of why society and organizations do or don’t need innovation. A need for Innovation is a given. Sincerely,Zachary Jean Paradiswww.creativeslant.com

I’m pretty much definitionally on board with Zachary above. Here are just a couple of thoughts, one hinted at already by Dave.If something is a real innovation, and not just a fuzzy or doctrinaire bright idea, it still requires patience and mentoring. A tiny example: my hairdresser subscribed to an on-line appointment site. Even though I am computer literate / dependent, I resisted the change as impersonal, not providing certain feedback information, the general learning curve, the expected malfunctions. Now I love it, making appointments in the middle of the night.Her solution with her customers was to–permit them to use the old system (phone) in parallel;–at the same time, keep showing them the new system.All this without insistence or impatience, and with humor.Mentoring the adaptation curve can be long, sacrificial, and risky, in that only at the end will the innovator find out whether customers quantify and weight the purported advantages as s/he does. If they’ve been “socially engineered,” they will be furious and become cynical about innovation, as people are with customer service voice-mail trees. So be careful of agendas. Is it serving their goals and values, or controlling them?I know a few people who live in gated communities (which I take to be Dave’s code for a well-above-subsistence income and enjoyably private private lives); and a good many of them would gladly contribute to, indeed step up and sponsor, real and promising solutions to social problems — say an extremely effective literacy module. Dealing with them puts a burden on the sketchy-bright-idea, of-course-it-will-work innovator to demonstrate utility and applicability in the real competitive resistant world of incentives and habits. But don’t count out the prosperous in North America just because they don’t subscribe to someone’s from-the-hip “Something must be done. X is something. X must be done.” Plenty of people with means are seeking effective & creative ways togive back. Philanthropy isn’t just ethical, it’s fashionable and psychologically rewarding. In fact, one of the real innovations will be to overcome hostility toward the well-off, to learn and teach how to reach them and match their means and hearts with elegant solutions to human problems. Hint: IMO part of the key is to go more personal / relational than programmatic, at the same time efficiently and simply administered. Small bureaucratic footprints, big bang for the outlay. Think Pareto, leverage, and measureable.

Aaack!! I forgot that paragraphing is not easy here!

I mistrust wide-reaching theories. Dave’s conclusion could be just an expression of his personal disappointment. Solutions could exist on a personal scale. How did he reach this conclusion? Could you write more about this, Dave?ZJP: If we must restrict the use of the word innovation to proven solutions that are available cheaply on the market, what terms should we be using instead? What about potential solutions that do not involve money or the market at all? Thank you, ZJP, for pointers. So far, my own best candidates for solutions are Technocracy Inc. and the work of Bernard Lietaer.If you continue to write about this, Dave, you have my interest.