I‘ve explained before that I’m not a believer in the myth of the Noble Savage. We are by nature, when faced with adversity, fierce creatures, capable of extraordinary violence and cruelty.

I’ve also written that, as many contemporary anthropologists have explained, the claim that prehistoric humans (i.e. humans prior to the recording of our culture, which began about 30,000 years ago) lived short, brutal, dangerous lives is complete nonsense. Although we can never know for sure, and while the believers in endless “progress” continue to pour on the propaganda that life has never been better, there is now compelling evidence that:

- Prehistoric humans who weren’t eaten by predators or struck down by diseases lived long (70-90 year) healthy lives. They suffered few illnesses except in areas of temporary overcrowding, had almost no dental diseases, musculo-skeletal or chronic diseases, and exhibited almost no signs of malnutrition.

- Because there was abundant food and an ideal climate at hand in the forest, and our numbers were small, we were, for most of our first million years on the planet, vegetarian gatherers (our running speed, teeth and fingernails are not designed for hunting or eating raw flesh), who “worked” to provide for our essential needs only about an hour a day. The rest of our time was spent in leisure.

- Prehistoric humans were tribal, communal, generous, social, cooperative and peaceful. Only on rare occasions, when tribal territories were invaded by another tribe which had (most likely) suffered from some natural catastrophe and were in search of new land, did we exhibit violence, and then it was fierce and short-lived. This is nature’s last resort, when peaceful means of dealing with unsustainable numbers (like diseases, and falling fertility rates) fail to rectify the balance.

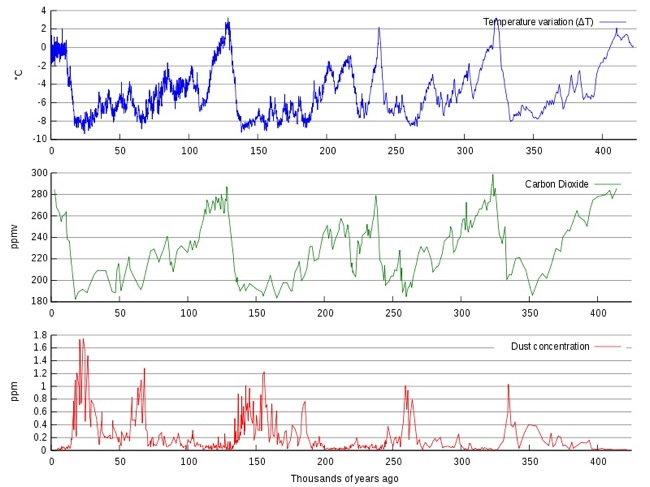

With the advent of climate crises like the ice ages and volcanic supereruptions (which may have repeatedly reduced human population to a few thousand people, perhaps as recently as 70,000 years ago), our species would probably have become extinct, had it not been for our extraordinary intelligence and (in desperate times) ferocity. First, we invented the wedge (the arrowhead, knife and spear) about 30,000 years ago, during the latest ice age, which allowed us, for the first time, to catch and eat large animals, so we could survive outside the jungle, our natural homeland for a million years. We then discovered (independently it seems, in many places around the globe) catastrophic agriculture about 10,000 years ago, which allowed us to settle. The result is the civilization we write about in our history (we have conveniently forgotten how we lived for a million years before history and civilization). Jared Diamond explains the consequences:

As population densities of hunter-gatherers slowly rose at the end of the ice ages, bands had to choose between feeding more mouths by taking the first steps toward agriculture, or else finding ways to limit growth. Some bands chose the former solution, unable to anticipate the evils of farming, and seduced by the transient abundance they enjoyed until population growth caught up with increased food production. Such bands outbred and then drove off or killed the bands that chose to remain hunter-gatherers, because a hundred malnourished farmers can still outfight one healthy hunter. It’s not that hunter-gatherers abandoned their life style, but that those sensible enough not to abandon it were forced out of all areas except the ones farmers didn’t want.

Archaeologists studying the rise of farming have reconstructed a crucial stage at which we made the worst mistake in human history. Forced to choose between limiting population or trying to increase food production, we chose the latter and ended up with starvation, warfare, and tyranny. Hunter-gatherers practiced the most successful and longest-lasting life style in human history. In contrast, we’re still struggling with the mess into which agriculture has tumbled us, and it’s unclear whether we can solve it.

No one is to blame. We did what we had to do to survive the catastrophic effects of climate change — and that has precipitated the sixth great extinction of life on Earth. We cannot change who we are, and we cannot undo what we have done. What is interesting to ponder is if, as I and an increasing number of students of history and current events believe, our civilization will crash by the end of this century, and we will be back to a situation similar to that of prehistory, what might we do then , to avoid repeating “the worst mistake in human history”?

(conception of art after the collapse of civilization culture by afterculture)

Suppose that, by 2200, with the collapse of our civilization, the world looks like this:

- Human population is back to 1800’s level of about one billion people, declining slowly by 1%/year (the reasons for this continuing decline are complex, and I may explore them in another article).

- About 97% of the population is living as farmers, using a variety of catastrophic agriculture and permaculture methods. Cities are mostly abandoned and used as a source of materials for scavenging for one-off manufacture of essential products, since there is no oil to power industrial machinery to make new mass-produced goods.

- A high quality of life has been achieved, due to the retention of knowledge about sanitation and disease prevention, and the abundance of scrap materials for building, making clothing etc. Most of our time is spent in leisure activities.

- There are much lower chronic disease rates, due to less stress, less pollution, and improved nutrition. Frequent pandemic diseases, however, ravage humans, farmed animals and catastrophic-agriculture crops — Our descendents are still suffering from the effects of lost biodiversity during the last civilization, one of which is increased susceptibility to pandemics.

- Societies are principally peaceful, and community-based. Everything is done on a small, local scale.

- Because of drastically reduced contact between communities (motorized travel has ended, and long-distance communications and information technology has proved too expensive to maintain due to material shortages), the new societies are astonishingly diverse and heterogeneous.

- Conflicts between communities are rarer, partly because contact is rarer, partly because lower population density and falling population means less stress on local resources, and partly because war technologies available for conflict have become unaffordable and fallen into disuse. The few conflicts tend to be between communities ravaged by monoculture crop diseases or severe climate events (mostly a consequence of what our civilization has done to our atmosphere) and nearby thriving permaculture communities.

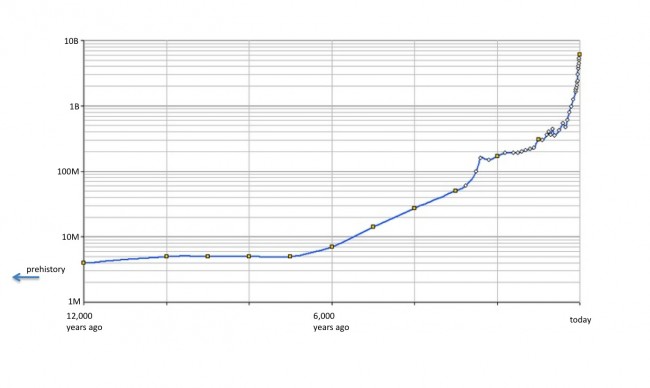

This is not a nomadic, gatherer-hunter society, since even before civilization desolated the Earth and its natural food-production capacity the global population of humans that could be (and was) comfortably supported as gatherer-hunters was only about three million, not a billion (see top chart above). These post-civ societies are, in this vision, slowly migrating from catastrophic agriculture to permaculture (the growing of plants sustainably in such a way that they require no weeding, watering or artificial chemicals, and propagate naturally).

Nature has, of course, always practiced permaculture. It is extravagant and inefficient compared to catastrophic agriculture, which is what she shows us after severe floods, fires and other land-clearing events. Our ancestors thought that the more efficient catastrophic agriculture would serve us better than permaculture, and that is what Jared Diamond calls our “worst mistake”. Might we be smart enough next time to adopt permaculture instead? My sense is that we will, but it will take time and ideological struggle before we get there, and by the time we do our population may well have decreased back to a hundred million or so (perhaps two millennia from now). All other things being equal, this might be the next great time to be living as a human on Earth, a time as full of peace, love, health, joy and abundance for our species as much of prehistory.

But there is another variable that Jared Diamond refers to — population growth. Gatherer-hunter societies self-limited their populations, partly by abortion or infanticide, and partly biologically — these societies nursed their babies until they were old enough to travel on their own feet with the tribe, and natural selection evolved us in such a way that women rarely get pregnant while they are still breast-feeding. So women normally only had one child every five years or so, since more than that would be too much of a burden to carry around on the nomadic treks of the society.

Civilized societies have no such burden, and nature (she works slowly) has not yet evolved a physical mechanism to reduce human fertility naturally (though sperm rates in males are now declining precipitously) to compensate. We have not been smart enough to balance our own numbers in the current civilization. Will we be smart enough to do it in post-civilization societies, especially when population is still declining?

I was thinking about this when I read Sex at Dawn, the book on prehistoric society and sexuality by psychologist Christopher Ryan and psychiatrist Cacilda Jetha. They cite several anthropologists whose conclusions about prehistoric life jibe with my own, above, and how agriculture changed the way we live: “Farmers, afraid of the wild, set out to destroy it.”

They explain how it is in our species’ best interest to be cooperative. Human remains older than 10,000 years show almost no evidence, they say, of violence or injury, especially the types of injury that result from conflict. They also dismiss many of the arguments about prehistoric human behaviour extrapolated from the study of today’s indigenous peoples, explaining that there are no gatherer-hunter cultures left on the planet whose ways of life have not changed drastically as a result of contact with the dominant civilization culture. We are all civilized, now.

They go on to compare the genetic makeup of humans compared to that of other mammals and conclude that we are much closer to bonobos than our other cousins, the chimps. For example, we share an oxytocin-release mechanism that brings us enormous pleasure and relaxation when we have sex, that chimps don’t have at all.

They also argue that, prior to the discovery of catastrophic agriculture, women were equal to men in all respects and in all group activities, because there was no need for specialization. With agriculture and the invention of civilization, the concept of personal property necessarily arose for the first time, and women became, like land and slaves and other ‘resources’, the unequal property of men. And with property came hierarchy, power politics, and then, as Jared Diamond said, “starvation, warfare and tyranny”. And as a result, women, enslaved in a patriarchy of scarcity, became anxious about their own security and jealous of others who had more. Women’s desire for male partners who offer them security, and both males’ and females’ jealousy and possessiveness are not inherent human nature, the authors claim, but the result of what civilization culture has done to us. They rail against the “Flintstonization” of our prehistory and the unquestioned belief (reinforced by the theories of Darwin and Hobbes) that prehistoric humans were much like civilized humans in their behaviours.

In fact, they say, what we know about anthropology and evolutionary biology suggests that prehistoric humans were almost certainly “fiercely egalitarian” (they would have found any hoarding, jealousy or possessiveness highly insulting and contemptible to the tribe, behaviour worthy of ostracism). As part of this fierce egalitarianism, they were, while responsible and nurturing of the young in the tribe, highly polyamorous (sexually active with many partners), free of jealousy, and generous in their openness to sexual advances.

They point to our (and our ancestors’) extraordinarily large testes, high sperm production, huge and constant sexual curiosity and appetite, and natural tendency towards (what is now disparagingly called) promiscuity (original and etymological meaning: “in favour of mixing without discrimination”), as evidence for their claim that, rather than competing for mates before copulation (as most mammals do), we are like the bonobos in letting our sperm compete post-copulation to ensure the optimal diversity and health of our offspring. Hence we are wired, they claim, to have sex often (many times per day) and without discrimination with many members of the opposite sex. Hence:

- the multiple orgasm capacity and loud vocalizations of women in sex, to attract more males, and make multiple couplings pleasurable for women,

- the fact that women’s orgasms tend to draw in the current partner’s sperm and expel the previous partner’s,

- the fact that having lots of orgasms reduces aggressiveness and stress and makes daily tribal life happier,

- the fact that paternity was impossible to establish and hence must have been irrelevant in prehistoric cultures, and

- the fact that monogamous marriage is such immensely difficult, unhappy, self-effacing work, and so often fails to last.

If prehistoric humans had a name for the members of their tribe they had sexual relationships with, that word would not be “spouse” or “partner” or any other word implying some form of exclusivity. It might instead be “consort” — literally “someone one shares and joins with”. We are meant, the authors conclude, to enjoy a lot of sex every day with many “consorts”, because it feels good, and is good in every way for us and our “tribe”.

So back to the question of whether or not, especially if we were to give uncivilized vent to our normal voracious sexual inclinations, a post-civ society would be able to control its population to avoid all of the problems that overpopulation produces. What’s interesting is that, despite their sexual promiscuity and vitality, bonobos on average give birth (to a single baby of course) only every five to six years — which is how long they nurse their young. Even before human habitat destruction made them an endangered species, their population was kept stable by the natural “birth control” of lactation, and by natural predators and diseases.

Post-civ human societies may well go back to nursing their young for four or five years, which may, in a healthy, natural human population, drastically reduce birth rates. Nature has already reduced human male sperm rates, though some of this may be due to high stress rates, hazardous substance abuse, environmental factors and modern malnutrition. But if post-civ societies retain our knowledge of health (especially sanitation and disease prevention), and if populations of human predators only slowly return to levels sufficient to significantly affect human numbers, what are the chances we will be able to avoid another human population explosion, and the commensurate catastrophic problems that would produce, all over again?

Perhaps I’m a dreamer, but I think the odds are pretty good. As our descendents rediscover that they are an integral part of all-life-on-Earth, and reconnect with each other and with the land where they live and the other creatures who belong to that land, I think they will instinctively and voluntarily reduce their birth rate to levels that are sustainable. I would argue that the low birth rates in affluent nations today are due primarily to awareness and hard-nosed adjustment to economic realities rather than a conscious or unconscious altruism, since citizens of those nations are especially inculcated in the civilization culture that inherently disconnects us from each other, from our senses and instincts, and from all life on Earth, and treats “the environment” and its inhabitants as an “other” for our arbitrary and exclusive use.

I’m also concerned that, along with the rest of the oil-economy-driven mass-produced trappings of global civilization, post-civ humans will probably not have access to reliable birth control products.

But somehow or other I believe that reconnected humans will just know that they have to reduce their numbers back down to the levels of sustainability. There is something about living a natural life integrally, as part of all life on Earth, that drives you to behave responsibly, not out of guilt, but out of love. Our inherent, human, lost biophilia.

If I’m right, after the dark of civilization’s collapse, life and sex at the dawn of the next human experiment on Earth may not be all that different from what is described as our prehistory in Sex at Dawn. A life and world full of fun and sensuality and connection and joy and peace and love and ease and passion and discovery and abundance and responsibility within community. This is what I see now and always in the life of wild creatures, having freed myself from the propaganda of “wild” life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short…[in] nature red in tooth and claw” (to conflate two pro-civilization shills, Hobbes and Tennyson).

I dream of such a natural life. I mourn its loss for myself and my fellow humans who will likely never truly experience it, that magic connection, that true presence, that unimaginable joy. My recent nighttime dreams have been of my prehistoric ancestors, back in that astonishing time when we were free.

And I dream for such a natural life for my tribe’s descendents two hundred (and two thousand) years from now, when the mess of civilization is behind us. That is who we’re meant to be, and how we’re meant to live.

I will do what I can do to make that dream true for them.

(charts above from Wikipedia)

Shall we call that “posthistory”, then? :-)

My guess is Christopher not Calcida is in the driving seat. Who knows, if born in a different time maybe I really would buy it, but I’ve got tell you in my dream world, sexuality is not like this. Is it the time that’s different or just male and female perspectives? Women can be persuaded to this point of view. In my experience, before long they change their minds.

In writing the book Diamond intended that its readers should learn from p.23 …… In the present book focusing on collapses rather than buildups I compare many past and present societies that differed with respect to environmental fragility relations with neighbors political institutions and other input variables postulated to influence a societys stability. The output variables that I examine are collapse or survival and form of the collapse if collapse does occur.

Pingback: Suppose that, with the collapse of our civilization, the world looks like this… « UKIAH BLOG

Where do you get this stuff Dave?

1. “invented the wedge (the arrowhead, knife and spear) about 30,000 years ago”, more likely 2+M yrs ago.

2. “we were, … vegetarian gatherers … who “worked” to provide for our essential needs only about an hour a day.” What compelling evidence? See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunter-gatherer

The culture of the Pueblo People of the Southwest provides a glimpse of a way of life that has incorporated agriculture as gardening communally and group and individual hunting. Their life ways have endured for over a thousand years…and they still work at least as well as those of the Great White Father.

Lee