I want to learn to meditate. More than that, I want to learn presence, the art of being in the moment, aware, relaxed, attentive, competently and appropriately responsive and adaptive, taking everything in intellectually, emotionally, sensuously, and instinctively, collecting, engaging others, letting things come, challenging, playing imaginatively and creatively with them, reflecting, understanding, synthesizing, integrating, acting responsibly and passionately, and letting go of what I cannot change or control. I think this is an essential competency, and I suck at it. I’m unintentionally inattentive and insensitive, and I have a terrible memory.

I am a great belief in self-directed learning — that, with sufficient self-knowledge, we are vastly better off deciding personally when, what and how to learn, and learning our own way at our own pace, than relying on education systems and processes that inflict a one-size-fits-all process that presumes what we should know and how we should best learn it. Most of that self-directed learning is solitary (though a mentor might be selected to bounce questions and ideas off).

I am also a great believer in on-line learning, since the essentially infinite resources of the web are vaster in breadth, depth and media than any preset course or curriculum taught in a classroom could ever hope to match.

But I’m learning that there are limits to what you can learn online, and what you can learn alone, even if your research and self-directed learning skills are exemplary. For example I have tried a dozen self-paced, self-directed ways to learn to meditate, from books, recordings and even a few real-time mentored telephone and face-to-face instructional sessions (thanks in particular to Indigo Ocean). Still, I cannot meditate.

I have come up with several excuses for this:

- I have taken hands-on courses in swimming, dancing and playing musical instruments, and haven’t learned from them either, so perhaps the problem isn’t that I’m trying to learn meditation online, it’s just that I’m hopelessly uncoordinated.

- I haven’t practiced much. There is a substantial consensus that learning difficult skills like meditation often only occurs with lots and lots of practice. So perhaps the problem is lack of practice, combined with lack of patience.

- There are limits to what anyone can learn, period. Perhaps with meditation I’ve just pressed up against another of those limits.

But I find these excuses unconvincing.

I’m wondering whether some critical skills and capacities are far better learned face-to-face, real-time, in a group. We often learn well from observing others doing and learning. And it seems almost ludicrous to think that essential skills like collaboration, empathy, mentoring and facilitation could possibly be learned online or alone, no matter how brilliant the simulation of others’ presence the Internet or self-paced learning exercises and case studies might provide.

My friend Raffi asked me the other day if I think I can really learn to meditate without a real-time, real-space ‘expert’ teacher. Reluctantly, I’m beginning to think the answer is no.

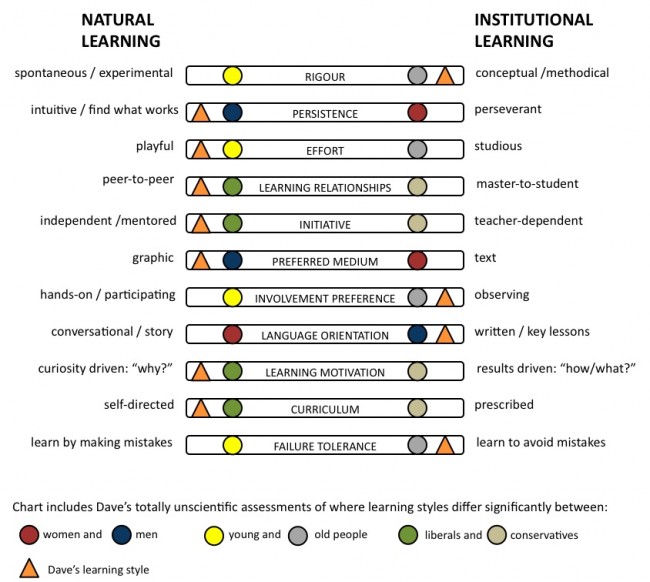

We all learn differently, of course, and for each individual there is a need for different types of learning to acquire different knowledge, skills and capacities. The chart above summarizes everything I’ve learned over the years about learning styles, along with a few really outrageous generalizations. I have always aspired to learn naturally (the left-side choices in the table above). However, thanks to my upbringing, my learning style might more accurately be labelled Old Liberal Male learning style.

Most of my actual, meaningful, useful learning (none of it in educational institutions) has come from either (a) solo research and study (mostly online) or (b) conversation and collaboration with people in real time and space (mostly working on real, long-term, important projects). I find (a) easy and fun, and I’m good at it. I find (b) arduous, and I’m terrible at it. I talk a good story about the value and importance of stories, learning-by-doing, empathy, learning from mistakes, facilitation, conversation and collaboration in community, and I really believe it, but if you want someone with skills in any of these areas, you had best look elsewhere.

Hence I am constantly bumping up against the limits of what one can learn alone and online. Here’s a controversial list of things I believe you can’t learn (very well) alone and online (or from books for that matter, since they’re more or less all online now):

- The social skills and capacities of getting along well and effectively with others (e.g. empathy, facilitation, conversation, collaborative skills, consensus, invitation, conflict resolution, improvisation, elicitation, story-telling).

- The wisdom of crowds (it’s just too hard to organize group brainstorming, focused knowledge-sharing, and Open-Space style creative interactions online).

- Anything about human nature.

- To really know yourself.

- Most self-sufficiency and survival skills.

- What you’re meant to do in this world, and with whom.

- How to be more truly yourself (e.g. generosity, vulnerability, taking responsibility, caring, drawing on instinct, intentionality, adaptation, resilience).

- How to really play.

- How to make a living for yourself.

- Competencies and capacities that require real-world practice (e.g. meditation, being present, languages, physical recreations and sports, dealing with illnesses and traumas, self-management, acceptance, and a host of technical skills).

This is an important list, and it’s just off the top of my head. What’s even more annoying is that learning a lot of these things doesn’t lend itself well to natural (or Old Liberal Male) learning styles.

So if I’m serious about learning to meditate and become present, not only am I going to have to turn off the computer and get with other people in real space and time, I’m going to have to try a new style. I may have to be perseverant and studious, learn to accept and follow instruction, follow a prescribed curriculum, get results-orient, and practice, a lot, even when it’s no fun. Ugh. Do I really want to learn this that badly?

That’s really what it comes down to, when push comes to shove on difficult learning. Pollard’s Law states: We do what we must (what we ‘have’ to do, our personal imperatives), then we do what’s easy, and then we do what’s fun. For me at least, learning meditation and presence is not going to be easy or fun. Is it enough of a personal imperative that I ‘must’ learn it, or will I fall back into the habit of doing things that are easy and fun instead?

The answer to that question is depressingly obvious. Things are the way they are for a reason. I have the time to learn these things, and I know I want to learn them, but I’m not doing it. Same applies to a lot of the things I think I want to do. Instead, I’m learning about and playing with Google+, online and alone (easy and fun). I know my limits.

Dave…investigate your aversion to practice. What holds you back from just sitting for ten minutes and watching your breathing? Don’t really newer that question, rather just do it.

With things like meditation, juggling, music, and so on YOU CAN’T GET WORSE BY PRACTICING. And you can’t get better by thinking about it. So I would encourage you to see that learning is also making your body do things over and over so you get better at it. You know this from running and other things. Meditation is the same. Practice actually designs our brains so that we get better at things. You need to train your brain and build the architecture for comptence by actually doing it.

And if you need a sangha to do it, there are some groups on the island that sit together. Ask how you can join them.

Hi Dave and Chris –

I have to disagree that practising can only make you better. If you practice something incorrectly, it is easy to pick up what the firearms community calls “training scars” – Bad habits that you must then unlearn. Allowing your mind to wander when you should be meditating or allowing distracting thoughts or feelings to emerge may build bad meditation habits.

I’ve been doing Zen for almost 3 years, and only in the past month or so have I become able to intentionally direct strong focus. It typically lasts a few seconds before my thoughts distract me and I have to refocus. I find it’s easiest to do when starting an intricate or repetitive task, but your mileage may vary.

As far as a teacher, Zen says you NEED one, but much of my master’s lessons can be reduced to the words “CUT THINKING!” Maybe Zen is a bad example because a conceptual understanding of it is ultimately an impediment to a direct understanding. Anyhow, I wish you luck on your path. It sounds like you at least have the right intention, which is essential. :)

Interesting pattern developing here: I’ve received quite a few comments on this post, but most of them are by private e-mail, or on my Google+ or Facebook feeds. Not quite sure how bloggers can integrate the conversations into something cohesive, until all this technology settles out.

I did delete one comment here on taking scientology courses for meditation. While I’m sure the writer was well-intentioned, I’ve known several people who have been seriously damaged by this cult, so mentions of it go automatically into my spam filter.

As always, I do read, appreciate and think about all the comments on my blog, even though I rarely respond to them.

I started to say a dismissive ‘I’m with Raffi here’, but decided to sit with your real questions a bit.

I think learning something that is both body-centered and spiritually focused like meditation requires, especially those of us who tend to experience the world through our minds, powerful motivation. For me the motivation to learn and practice and stay with a meditative practice is pretty uncomplicated and maybe even self-centered, I guess: I feel better when I do it. I feel more connected to more of me. More spacious, humble and joyful. Sometimes deep rumbling laughter seeps up through the layers as I sit or walk or dance (all parts of my practice). These are stimuli that I want to encourage, so it’s a simple feedback loop.

Your list of what is difficult/impossible to learn online was a good one, and explains a bit why I’m reluctant to spend much time with my computer, at least during parts of the year (summer). Seems I prefer to be directly experiencing the world, like a plant–I guess I’m making and storing some variety of human chlorophyll–for reflection and reconstitution in other parts of the year or even my life. I don’t really want to spend a lot of time with the computer and prefer to be hiking, kayaking, laughing, gardening, just sitting on my back porch with the dogs and a glass of wine, watching the flowers do flower things.

Body knowledge is so different from mental knowledge. And it’s what I am leaning towards, again like a daisy towards the sun. And some body knowledge while it only be gained by muscle, sinew and cellular reactions, is best mirrored by another human. Such has been my experience with a variety of meditative modalities.

Thanks for bringing me to the computer, Dave!

A reader (who wishes to remain anonymous) writes:

Dave, I appreciate your honesty. and i appreciate that your answer is “no,” that you can’t learn this on your own…it takes some courage to say, “i do need a teacher.” and in the parts of the world where you and i live i think there are a fair amount of good teachers out there.

I want to offer my two kopecks (rials?) , as it were, to respond to a few things here which i imagine may sound obvious but i think are important to be explicit about.

also, i want to qualify my response by saying that i’m relatively new to the practice– only about 5 years in…one of teachers at my zen center likes to say that you only really get the hang of things – that you stop being a “pup”- after about 10 years of practice. and every time I bring this up, she ups this by 5 years (we’re at 20 years at this point!). i think that’s in part her way of saying that in order to really get to practice (or let practice get to you), you really have to let go of any expectation or hope of “getting” anywhere (attending to spiritual bypassing).

from my (leaning) belltower, it is not so much about learning a new activity but learning and integrating a practice of mindfulness. Treating it as learning a skill risks turning it into another ‘it,’ another thing to be mastered, another thing that is outside of us. to be clear, i’m as guilty of this as the next person…and it’s all the other practices one learns at a center that one may apply over the course of the day that the experience of sitting helps support. i just find that with the regular sitting,i’m more apt to notice my attention drifting in the course of the day, or that i feel shitty, resentful, etc. and there’s more likelihood as a consequence to do the other practices to attend to these different states.

and there are many paths to this, of course. and some of these paths consciously de-emphasize a practice of still, silent sitting (non-dual traditions like advaita, for example). so, yes, meditation in and of itself is a new skill, but that’s a limited way of talking about it, in my opinion.

one of the things that many of us find over the years of practice is that we are not who we think we are. i imagine there’s a lot of truth to what you understand to be your learning style. and i imagine that with a practice your understanding of (and beliefs about) how you learn would change…

my practice has helped me connect me more and more with my self-hate, self-loathing, oh-so-gradually see my own laziness (if that’s the word), addictive tendencies…and, that said, there is that deep yearning within me that gets my ass out of bed on most saturday mornings – even when i’m depressed – down to the zen center and then cop to the teacher that, yes, i feel like shit. …and that’s a-ok…

so, do i know how to meditate? i think a fair number of us meditators would acknowledge that our attention drifts, that we daydream a fair amount during a sit. so, perhaps it’s a willingness to sit one’s ass down and attempt to do the practice than to learn how to do it…one thing i’ll add, though, from my experience. my first experience of a meditation retreat was a ten day vipassana course. this was really rigorous, up at 4am, ass on the cushion at 4.30 (for a two hour sit)…but doing it over ten days produced a tangible result even though i meditated very unskillfully (and i imagine i’m just a little less unskillful today)…

re; finding teachers– i’m definitely grateful for my teachers. also, if you should look for a teacher, i like the reframe of a practice buddy– he prefers to think of being the good student as opposed to finding the “perfect” teacher…and this comes from someone who is very much a doubting thomas…for years he wouldn’t go to private interview to the teachers…and for years he would just say he doesn’t trust the teachers at all…

also, a note regarding the one commenter who suggested scientology practices. i have heard from at least two people that those practices are helpful…and, of course, there’s no way i’d be willing to learn something helpful in, what i suspect, is a cultish environment…

Hi Dave,

We’ve already had a number of conversations about meditation, so you already know my views on that ;-). My start was a 10-day vipassana course from Goenkaji (dhamma.org). Very clean both in practice and ethics. Householder focus, which is a very helpful orientation for most of us.

I’d like to suggest another controversial add to your list of things that can’t be learned alone. Non-violence and peace. My ongoing study of aikido has brought this initial intuition into much sharper focus and i now strongly posit that without an active embodied practice (with others) a commitment to peace and non-violence is little more than wishful thinking. Without being brought face to face on a regular basis with our own conditioned responses of aggression or flight, how we think we will respond is largely fantasy. If we want to have access to genuine choices in moments of threat, we need others to help us practice by evoking our conditioning so we can work with it. (but maybe this is included in your broad category of “anything about human nature” ;-) )

Blessings,

Wendy

Pingback: The Limits to What You Can Learn Online or Alone « how to save the world | E-Learning-Inclusivo | Scoop.it

Pingback: The Limits to What You Can Learn Online or Alone « how to save the world | Educación y TIC | Scoop.it

I learned meditation when i was 23 (late ’90s) before ever using the internet, from a book by a prominant swami, and i think it was called simply “meditation”. This small, yellow-colored minibook covered the basics which “are really quite simple”, as John Cleese might say. (The body to be relaxed but in a position to foster attentiveness; spine straight (actually i have meditated while going to sleep many times and in odd positions over the years). One gradually relaxes the body so it can have its own sort of stillness, and the body and mind mirror one another, partially in the sense that health or silence in one aspects the other.) Even the initial relaxing process can be seen as a sort of meditational focus, intended to strengthen the ability to calm the mind. Once relaxed and in one’s preferred position/stance, one focuses on something and begins the meditation proper… be it a visualized object, one’s whole body (‘zazen’), the breath, or perhaps just a tiny tiny point. Though the mind will wander away, one just keeps going back to the focus of the meditation. This ‘trying’ to meditate phenomenon is valid enough as it exercises parts of the brain and helps train the consciousness, or untrain it from certain lobes of the brain so-to-say… and the actual meditation typically becomes cumulatively easier over the months, years.

I would lock myself up in a bathroom — while i was working haha– for 15 min a day when i 1st endeavored to meditate. It took a few months to get it really going, and i was pretty inspired to do it which really helped to facilitate the motivation and time for it. Eventually the quality of meditation became embedded in my consciousness so that i could apply it to anything, and do it eyes open .. “meditation makes a groove on the mind that never goes away”

Please have a look at http://www.watkowtahm.org/. Teaches you how to do it and why, with two exceptional western teachers, in a very helpful setting. After many years of struggling and frustration, I finally managed to meditate, there. But it is only the beginning of the journey..

Dave, like you I’m a self-learner in many areas (especially in my career of software development) but I’ve also found that both self-learning AND community-learning are important in areas such as Permaculture, Transition Towns, and meditation. I think that the various spiritual paths each appeal to different types of people but that they all go to the same goal: awareness of unity, and the joy and living-in-the-moment that come with that. For myself, Eknath Easwaran’s path of passage meditation has helped me for three decades and I like his style: non-dogmatic, practical, for people living in the world, yet based on fundamentals that are thousands of years old.

Easwaran himself died in 1999 but his work is carried on by his wife, close students, and fellowship groups around the world. Other info and even an online(!) introductory course are at http://www.easwaran.org

Best wishes in finding a path that works for you.