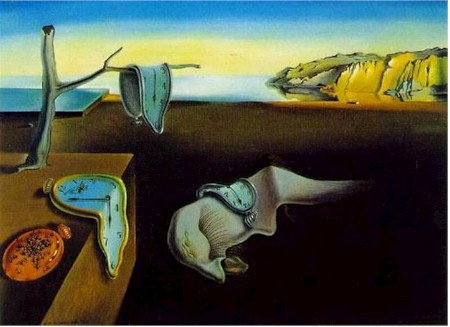

(This is a rather silly post about our clumsy measurement systems, and how, if we were to reinvent them, we might come up with something much more intuitive and easy to remember; skip it if you’re busy, since I have two more important posts coming soon. The image above is Dali’s “Persistence of Memory”, portraying our most diabolical measurement device.)

We humans tend to prefer measures that we can relate to something tangible and permanent, like the day and the year as our principal measures of time in virtually every calendar. We know how big a foot is — in an average farmer’s work boot, it’s a foot long. An inch is the width of an adult male’s thumb, and since that is almost precisely 1/12 of a foot, the word inch (meaning one twelfth) was chosen for it. The Romans had an average walking stride of 2.64 feet, so they called two strides (one stride with each foot) a pace, and measured longer distances in thousands of paces (mille passus, shortened to mile). We measure the height of horses in “hands” — using the width of our hand including the thumb, measuring hand over hand (that hand width is now standardized at 4″). The Romans and British once used actual stones to measure their weight on a balance scale, and they knew the heft of a stone. For smaller weights, they used grains of wheat, or, for metals, a carob bean (which became known as a carat).

This might be a credible excuse for Americans’ refusal to adopt the metric system, except that most Americans have no idea of the anthropomorphic origins of their measures. To me, this refusal to adopt the system used almost everywhere else on the globe reflects their dominant culture: contrary, ruggedly and defiantly individual, arrogant, profoundly conservative and resistant to change. The British still refer to their weight in “stones” (one stone being about 14 pounds); they’ve gone halfway metric and seem determined to go no further, perhaps for similar reasons.

What we measure, and how we measure it, reflects our culture. Canadians somewhat grumpily adopted the metric system, knowing that they’d have to contend with Americans next door who would not. We did so I think because we are adapters, consensus-seekers, and idealists, and it seemed like a good idea at the time.

Our modern measures are often abstract. It’s hard to relate to pounds, ounces, grams, kilograms, degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit. Some of our time measures, like seconds, minutes, hours, weeks and months (though the month is vaguely related to lunar cycles), were arbitrarily set, and it’s only due to practice and cultural acclimatization that they mean anything to us. The idea of moving to decimal measures at least makes sense because it relates back to our digits, our basic physical way of counting.

What would happen if we set aside the culture-based measures we use and converted to a set of measures to which we can physically and directly relate, and made all other measures decimal derivatives of these basic ‘universal’ measures? I’m not advocating we try to implement this (our culture is so strong that changing measurement systems is almost humanly impossible) — I’m just putting it out as an intriguing thought experiment:

- Length: The standard measure of length might be one walking Pace (p), 2.64′ (80 cm, under the current metric system). The DeciPace (dp) would be one tenth of that, the width of your four fingers excluding thumb. The CentiPace (cp) would be one tenth of that, the width of a standard pencil. Anything smaller than that we’d leave to the scientists and advertisers, who use milli- and micro- and nano- to make really tiny things sound substantial. A KiloPace (kp) would be 1000 Paces, the distance we can walk in 10 minutes (though see the comments below on time measures), run in 5 minutes, or drive in the city in 1 minute. Anything larger than that we’d leave to the astronomers, poets and philosophers.

- Area: A Square Pace (p2) would then be one walking pace by one walking pace. A small apartment would be 70 p2, a small house 200 p2, a large house 400 p2, a small building lot 300 p2, and the area a farmer with oxen can plough in a day (an acre) would be about 6000 p2 (80 p x 80 p).

- Volume: One Cubic DeciPace (1 dp3=1000 cp3) would be about the volume of two mugs of coffee. The spoon in that mug would hold about 8 cp3, which is 2 cp by 2 cp by 2 cp. Your gas tank would hold about 100 dp3.

- Weight: The standard measure of weight might be one Book (b), equal to the average weight of a trade paperback. The average person would weigh about 200 b. The water or coffee in your mug would weigh 1 b. Your average car would weigh 3000 b if you’re in Europe or Japan, 4500 b if you’re in North America.

- Time: A day is a day and a year is a year. Everything else would a fraction of that, using Internet Time. Time notation might be yyyy.ddd.mmmmm and each day might start at the midpoint between sunrise and sunset at equinox at Greenwich UK. So at that time in Greenwich tomorrow, everyone in the world could sync their watches to 2011.234.00000. If you spoke with someone at that time and wanted them to call you again seven days later half-way through the day, you’d log it in your calendar as 241.50000. If you lived at the latitude of Greenwich your posted work hours might be daily .30000 – .67000 and, while it would be the same time everywhere on Earth, the person working the same shift a half-world away would have posted work hours as daily .80000 – 1.17000. If you took a flight that took a quarter of a day starting at .80000 the flight arrival and departure would be shown as Dep .80000 Arr 1.05000. Your midday lunch break or favourite TV program in Greenwich might run from .48000 – .52150. To ease the world towards a steady state economy we might encourage employers and self-employed to work only five or six days out of every ten, so if they were 3 on, 2 off, 3 on, 2 off, you might work days ending in the digits 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9. Calendars might have 10 columns and scroll either 4 rows at a time (maximum information that would fit on one screen) or 9 rows at a time (to show each of four ‘seasons’ in turn) with the last 5-6 days of the year in a final row, perhaps celebrated as a global holiday. To specify recurring annual events such as a birthday on the 173rd day of the year you might denote it as *.173 and to specify a recurring event on days ending in the digits 2 and 7 you might denote them as *.**2 and *.**7 or simply as **.2 and **.7. We might soon get accustomed to having someone say they would be back in .01 d (10 millidays, 10 md), and accustomed to setting the microwave for .001 d (1 md).

- Speed: Normal walking speed using the above measures would be about 150 p/md, running speed about 300 p/md, and city driving speed 1500 p/md.

It’s fun to think about anyway.

Speaking of measures: When I first started my blog, in doing some design for a game I compiled some prices-per-pound for various consumer products and ranked them from cheapest to most expensive. I recently did this again, and the rankings are shown below.

The biggest changes in 8 years? Food prices per pound are up about 60% compared to 2003 (that’s a lot more than the ‘official’ inflation rate of course). Digital electronics are down about 50% over the same period. Brand names cost on average twice what near-equivalent no-name products do, which I would guess goes entirely into advertising, executive salaries and profits. Some of this data may surprise you. All numbers are retail price divided by weight excluding packaging. Foods are in black, household and pharma products in blue, and other manufactured goods are in red:

| Coke, large bottle | $0.83 |

| Bananas, organic | 0.99 |

| Whole Wheat Flour, organic | 1.32 |

| Grape Juice, reconstituted | 1.50 |

| Orange Juice, fresh bottled | 1.58 |

| Gasoline, regular | 1.63 |

| Bread, white no-name | 1.79 |

| Potatoes, bag | 1.89 |

| Pears, organic | 1.99 |

| Peanuts | 2.23 |

| Lettuce, organic | 2.49 |

| Riding Mower, Poulan | 2.62 |

| Cast Iron Skillet | 2.87 |

| Broccoli, organic | 2.99 |

| Bread, sprouted whole grain | 3.29 |

| Sofa Bed, midrange IKEA | 3.54 |

| Mouthwash, Scope | 3.80 |

| Berries, fresh in season | 4.00 |

| Water, Perrier bottled | 4.21 |

| McDonalds Large Fries | 5.63 |

| Chicken Breasts | 5.66 |

| Peanut Butter, organic | 5.79 |

| Car, 2011 Hyundai Sonata new | 6.23 |

| Antacid, Tums Tablets | 6.28 |

| Soap, Dove bars | 6.67 |

| Red peppers, organic | 6.99 |

| Croissants, Pillsbury | 7.04 |

| Potato Chips, Lays large bag | 7.22 |

| Big Mac | 7.51 |

| China Cabinet, Carriage House, birch/cherry | 8.33 |

| Chocolate, Snickers | 8.64 |

| Pork Ribs | 9.33 |

| Salmon fillets, wild | 9.57 |

| All-Electric Car, Nissan Leaf 2011 | 10.40 |

| Cashews, organic | 10.41 |

| Cordless Phone, Vtech 2-handset | 11.33 |

| Ground Cumin, organic | 12.76 |

| Filet Mignon | 12.80 |

| Chocolates, Turtles, bag | 14.36 |

| Cheese, cheddar | 15.40 |

| Bathrobe, Egyptian cotton | 20.00 |

| Deodorant, Mennen speed stick | 22.67 |

| Electric Bicycle | 24.66 |

| Vanilla Extract | 28.50 |

| Deodorant, Lady speed stick | 29.84 |

| Light Bulb, GE 4-pack | 30.22 |

| Guess Women’s Daredevil Jeans | 35.60 |

| UGG Women’s Aussie Sheepskin Boots | 36.00 |

| Green tea, gunpowder organic | 36.87 |

| Shark Cartilage, packaged arthritis relief | 38.50 |

| Headache medicine, noname acetaminophen | 42.80 |

| Veuve Cliquot Champagne Brut Yellow | 68.00 |

| Headache medicine, Tylenol caplets | 119.61 |

| Camcorder, Sony digital | 158.18 |

| iPad 2 with wifi & 3G | 228.71 |

| Camera, Canon EOS Rebel SLR | 235.83 |

| Watch, Men’s Seiko LeGrand | 274.29 |

| Rescue Remedy, bottle | 386.36 |

| Chanel #5 Perfume 3.4 oz | 470.59 |

| Emporio Armani Men’s Sunglasses | 1645.00 |

Great choice of image: Dali’s “Persistence of Memory” has always been a favorite … and definitely a good starting-off point for all sorts of thought experiments. It’s an interesting question, too — what do we measure, why and how? Everything is, ultimately, so arbitrary, and fails to reflect true costs (ie, impacts on health, the environment, scarcity of resources, etc.) thanks to our skewed economic system with subsidies, tax breaks, etc. No wonder we’re all so uncertain as to what has lasting value these days.

Thanks for some food for thought :)

Way back in 1957 I bought my first car; a brand-new VW Beetle, which took sixth months to arrive, so I took delivery in early 1958. As I recall, it cost almost exactly $1.00 per pound, all-up, including delivery charges, license, misc. fees and a full tank of fuel.

oops! – that’s six months

Great choice of image: Dali’s “Persistence of Memory” has always been a favorite … and definitely a good starting-off point for all sorts of thought experiments. It’s an interesting question, too — what do we measure, why and how? Everything is, ultimately, so arbitrary, and fails to reflect true costs (ie, impacts on health, the environment, scarcity of resources, etc.) thanks to our skewed economic system with subsidies, tax breaks, etc. No wonder we’re all so uncertain as to what has lasting value these days.

+1