This is another in my series of articles exploring the basic existential questions of who we are and what motivates us to do what we do. For those puzzled about what that has to do with “saving the world”, my answer is that if we hope to be able to organize with others to make the world a better place, and deal with the huge crises we are now beginning to face, we are going to have to be cognizant of the truth of human nature, and specifically these existential questions. There is no point hoping millions or billions of people are going to change their beliefs and behaviours if such change is just not in our nature. And, as regular readers of this blog know, I am inclined to believe it is not in our nature, though I’m open to evidence to the contrary.

My friend Dale Asberry has been writing about “human cognitive failures” and put me on to this article in the extraordinary Less Wrong wiki, about whether what we want and what we like are different, and if so how and why. At the same time, my contacts who are members of Quora, a collective brainstorming site on deep philosophical questions, have been pinging me about the threads related to the existence (or non-existence) of free will.

As I wrote last year, my position on who we are and the existence of free will is as follows:

- The cells and organs of our bodies evolved our brains as a feature-detection, protection and mobility management device for their purposes. The ‘existence’ of our minds and identities as ‘individuals’ is therefore a self-deception. Our minds are nothing more than processes carried out for the benefit of our cells and organs — they are their information processing system, not ‘ours’.

- Like most species, we are social creatures that have evolved codes of behaviour that enable us, as part of the larger organism of all-life-on-Earth, to collaborate, share and keep our numbers in balance with the local ecosystem — these are all evolutionary selected behaviours, since they enable us to adapt and fit well into these ecosystems. These learned codes of behaviour are called cultures.

- In times of stress, due to overcrowding, natural disasters, climate change or the exhaustion of local resources, cultures can intervene to act in adaptive ways that would be unneeded in normal times, including war, migration, adoption of new diets, new tools and new ways of living that are better suited in evolutionary terms to the changed environment. At some point some of our species chose to leave the trees of the tropical rainforest where we lived a leisurely life as vegetarian gatherers for a million years, and struggle to survive in other environments. We evolved weapons to kill other animals, enabling us to live as carnivores, and discovered ‘catastrophic’ agriculture, enabling us to live where there was insufficient food growing naturally. These new tools, however, required settlement and a very different kind of culture — civilization culture — to sustain.

- Civilization culture requires sacrificing a great many freedoms for the survival of the collective membership, and requires vastly more work, personal sacrifice, hardship, suffering, and vulnerability to catastrophe than other cultures. To keep people from obeying their cells’ and organs’ natural tendencies by just walking away from this culture, it is of necessity inherently coercive, using hierarchy, violence, threat of imprisonment, propaganda and other means to ensure obedience and conformity of the group.

- Whereas our cells and organs had nearly full control of our (their) minds before civilization culture evolved, the new culture was able, through language and coercion, to influence and seize control of a significant part of our minds. There has been a continuing and escalating war for control of our minds ever since. Our culture persuades us that we have ‘free will’ to ignore what our cells and organs impel us to do and instead do what it (our culture) wants us to do — that we have an ego, an identity, and a responsibility to conduct ourselves according to the rules of civilized society, or we must face the social consequences.

So ‘we’ are, essentially, helpless witnesses in an endless struggle between our cells/organs/bodies and our culture for control of ‘our’ minds, and our beliefs and behaviours reflect who has ‘won’ each battle in that struggle. By contrast, our close cousins the bonobos (yes, I know they aren’t perfect either) are at peace — there is no inherent conflict between what their bodies and culture want, no scarcity, no imposed responsibility, almost no aggression, no monogamy or jealousy, no hoarding. And their only real stress is caused by our brutal, cancerous culture, which is extinguishing theirs.

Where does ‘liking’ versus ‘wanting’ fit into this model of who we are? Things we like (such as being in love, being in nature, listening to music, play, learning and helping others), according to the Less Wrong article, are different from things we want (such as sex, addictive foods and other substances, attention, appreciation, and acquisition of shiny objects — all things that in our modern culture are usually scarce). When we do or get things we like, we are happy. When we do or get things we want, we are often not happy — just (for a time) satisfied. Wants are cravings; likes are joys. Needs are another matter entirely — none of the “wants” listed above are really needs, the way that nutritious food, water, warmth, and social contact are — things we cannot live without. Wants could be seen as the midpoint of a continuum between likes and needs. Some things may be both wants and likes — beauty, for example, may be something we crave (especially if our world offers little of it) but is also something we derive genuine happiness from.

An example to explain the difference: For many years I hosted and organized monthly neighbourhood poker games. The game was small stakes with strict limits, couples and total novices were welcome, and we played “dealer’s choice”, developing over the years a list of some 100 variants, some of them really silly. Really serious poker players who had to win to consider the event a success, generally dropped out after one or two months. Much of the game was about learning, sharing, showing, and inventing new games. It was fun, and generally people were happy, win or lose. But everyone sometimes got unhappy if they lost too many times in a row, or lost a large pot by a very close margin. At these points, when tension rose, liking to play became wanting to win. Joy became addiction to the ‘high’ of taking risks and winning big. The nights I liked best were the ones where I came out ahead, but not too far ahead, and not as a result of any one person’s loss. Yet I know there is a gambler in me, someone who wants to win more than he likes to play. When I get stressed, I distract myself with video games (including poker against computer opponents) and I want to win (and get upset when I don’t, even though there is no ‘real’ money involved).

Scientists now say that the chemical reactions in the body when we ‘want’ something (dopamine-based) are different from those when we ‘like’ something (endomorphin and enkephalin based). Why would this be so?

My hypothesis is that this different chemistry evolved to suit different requirements: Our wants take precedence in times of stress or scarcity, while our likes take precedence in times of peace and abundance. When we can “afford” it, we do what we like; the rest of the time, we do what we want. This does make sense in the context of wants being more urgent and closer to needs.

Creatures in the wild, according to some biologists, spend most of their lives in “Now Time” — present, blissful, unaware of the passage or even existence of “Clock Time”. During this time they are happy (that’s in the best interest of the perpetuation of the species) and their lives are seemingly eternal. Their body chemistry in this state is driven by endomorphins (not to be confused with endorphins) and enkephalins, which create a feeling of bliss.

In times of stress or scarcity, however, wild creatures snap into “Clock Time” (the instantaneous time-sensitive state that most humans spend their entire lives in), and hormones are produced to equip the body for fight-or-flight. They are driven then to satisfy immediate needs and wants (safety, food, victory over a predator or enemy etc.), and their body chemistry in this state is driven by dopamine — which immediately flushes the body when a craving for one of these needs or wants is satisfied. Not the same thing as happiness at all. When the crisis has passed, the creature returns quickly to Now Time, and the endomorphins and enkephalins again take charge of the body, seeking happiness.

Except for the few humans who are able to set aside the constant and chronic stressors of modern civilization culture (through meditation or other relaxation/awareness/presence practices), we humans spend all our lives charged up and seeking the satisfaction of our endless needs and wants, the dopamine “rush”. And our industrial civilization culture, which now depends on a constant growth of consumption, encourages this by creating additional “needs” and anxiety about scarcity and inadequacy. We’re never really happy, only temporarily satisfied.

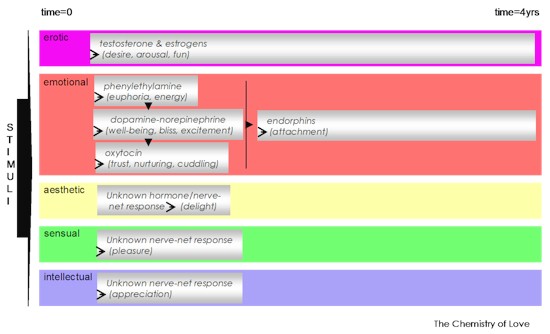

My guess is that the emotional and erotic response stimuli shown in the Chemistry of Love chart above, are primarily “want” chemicals, while the aesthetic, sensual and intellectual response stimuli in the chart are primarily “like” chemicals. Science remains almost entirely clueless on this, however, so this is only a wild guess.

This is part of the reason, I think, that we humans have become so utterly disconnected from Gaia, from the land and place where we live, from all-life-on-Earth. That biophilia connection is a “like” connection, which only few humans, rarely, really feel, so deeply are we buried in the chemistry of unfulfilled needs and wants. Yet our instincts, I think, still “know” and long for this connection, and every once in a while, in those still, peaceful moments of deep relaxation and awareness, we become present, shift into Now Time, and start to resonate with the ancient and delightful chemistry of what we really like, beyond wants and needs.

That is why I believe that the essential preparation for the coming economic, energy and ecological crises, culminating in the collapse of our exhausted civilization, is re-acquiring those essential capacities that will lift us out of the culturally-created illusion that our world is one of endless conflict and scarcity, full of unmet needs and desperate wants, and move us into the real-ization that a better, simpler life is possible, one almost entirely without wants or needs, one where we are free to enjoy what we really like — being in love, being in nature, listening to music, play, learning and helping others, all things that are and have always been free.

Only then can we realize that our civilization culture cannot be reformed to provide what we want and need (in fact its purpose is to create more and greater wants and needs). And by its very design, it will never make us happy.

Hi Dave —

However much supposition and guesswork may be involved, I think you are nailing this like-want thing down pretty damn solid. My gutt says. Yes! Absolutely. Good Stuff.

But…. I do have to give you a bit of a hard time. In your summation at the top… you combine our ancestors leaving the trees and the development of civ as if it all happened in short succession. But it was Australopithecus that left the trees. If you *want* to imply that that was the last time we were happy, well, then WE never were. But there was another half million years of evolution, and once homo sapiens showed up there was still another 100,000 years before civ reared up. So there WAS a time when WE were happy that did not involve living in trees as (primarily) fruitarians. For evidence of that, all we need do is look at the *primitive* cultures we have encountered in the modern world (as few as there are yet existant).

much love…

Janene

Hi Dave,

I’d love to read your answer to Janene!! Janene, what do you think of Elaine Morgan’s Aquatic Ape Hypothesis?

Best wishes

DT

DT —

I think it is very reasonable. I have heard variations on the AA theory that would have as spending a period as aquatic mammals — like a dolphin — and there is nothing to support that and no period in our evolution that is “unknown” enough to credit it. But the idea that we evolved along rivers, in marshes and on the coastline answers a lot of questions and there is growing evidence (recent digs have found our ancestors moving along the north-eastern coastline of Africa and into the middle east from there) that is probably correct.

Janene

Hey Janene: belated reply to your comments in our ongoing debate about the nature of prehistoric humans. Darwin talks about survival of the “fittest”, by which he meant those who “fit in” best to the environment in which they live. I think the bible story about being tossed out of the garden when we ate the forbidden fruit of knowledge is a brilliant metaphor for prehistoric humans’ leaving an environment in which we naturally “fit” in order to see if we could change the world to “fit” us. My sense is that it was when we stopped fitting ourselves to the world in which we lived (either because we chose to or because, due to climate change, we had no other choice), and started to try to change the world to fit us, we ceased to live in Now Time and entered the perpetual hell of Clock Time, and ceased to be happy. John Gray says “we will never live in a world of our own making”. We cannot. It’s an exercise in agonizingly prolonging the status quo until the inevitable falling apart of the crude and fragile complicated devices we have created to try to conquer the complex world occurs.

Closing comments thread for this post, since it’s being inundated with spam. E-mail me if you have further comments.