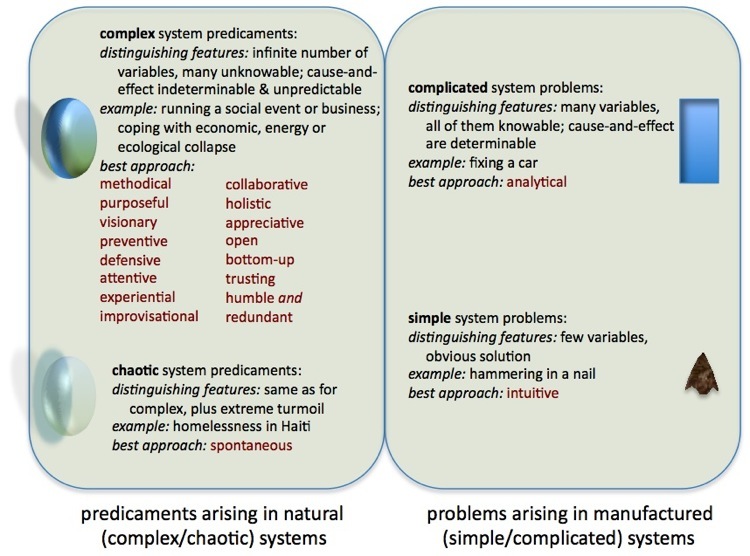

diagram from my earlier blog post explaining what complex systems are and how they differ from ‘merely complicated’ systems

In last week’s New Yorker, Adam Gopnik laments the epidemic of imprisonment in America, especially of the young and visible minorities, and explores what leads a society to give up on, incarcerate and hence enslave so many in brutal, soul-destroying institutions. In the article he describes the atrocity of privatization of prisons:

No more chilling document exists in recent American life than the 2005 annual report of the biggest of these firms, the Corrections Corporation of America. Here the company (which spends millions lobbying legislators) is obliged to caution its investors about the risk that somehow, somewhere, someone might turn off the spigot of convicted men:

“Our growth is generally dependent upon our ability to obtain new contracts to develop and manage new correctional and detention facilities. . . . The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by our criminal laws. For instance, any changes with respect to drugs and controlled substances or illegal immigration could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them.”

Brecht could hardly have imagined such a document: a capitalist enterprise that feeds on the misery of man trying as hard as it can to be sure that nothing is done to decrease that misery.

Gopnik reviews both the history of incarceration worldwide, and the circumstances that have led to different policies and approaches to defining, controlling and dealing with “crime”. He describes the precipitous decline in serious crime in New York and other large cities over the past two decades, and concludes that all three of the popular theories for this decline are wrong. Liberals are wrong to believe that better social programs and “broken windows” preventative programs are responsible — there is simply no evidence to support any correlation. Conservatives are wrong to believe getting tough on crime and more rigorous enforcement are responsible — if anything such actions have worsened the situation by leading to embittering enforcement excesses. And the statisticians who believe (as reported in Freakonomics) that it was the drop in birth rate among the poor and disadvantaged (as a result of Roe vs Wade) that is responsible, are also wrong — correlation doesn’t always mean cause and effect.

What led to the decrease, Gopnik found, was the combined effect of millions of small sustained actions by millions of determined people just trying to make their corner of the world a little better:

Epidemics seldom end with miracle cures. Most of the time in the history of medicine, the best way to end disease was to build a better sewer and get people to wash their hands. “Merely chipping away at the problem around the edges” is usually the very best thing to do with a problem; keep chipping away patiently and, eventually, you get to its heart. To read the literature on crime before it dropped is to see the same kind of dystopian despair we find in the new literature of punishment: we’d have to end poverty, or eradicate the ghettos, or declare war on the broken family, or the like, in order to end the crime wave. The truth is, a series of small actions and events ended up eliminating a problem that seemed to hang over everything. There was no miracle cure, just the intercession of a thousand smaller sanities. Ending sentencing for drug misdemeanors, decriminalizing marijuana, leaving judges free to use common sense (and, where possible, getting judges who are judges rather than politicians)—many small acts are possible that will help end the epidemic of imprisonment as they helped end the plague of crime.

Gopnik is saying, in effect, that complex ‘problems’ like crime, poverty, climate change, peak oil, corruption, pandemics, and unsustainable growth economies, are not ‘problems’ that can be ‘solved’ at all, but rather, as philosopher Abraham Kaplan explained, predicaments that must be “chipped away at” and adapted to. Our species tends to loathe complexity, and prefers to oversimplify everything, and the politicians, lawyers, corporations and media play on that loathing by always proposing analytic (“A or B”) dichotomies and simplistic “answers” — which cannot possibly work. “Three-strikes” laws, “trickle-down” economics, emissions trading schemes, subsidies, religious taboos and inquisitions, austerity programs, prohibitions, bailouts, military invasions and “quantitative easing” — these are all massively expensive complicated “solutions” to complex “problems”, and they have all failed spectacularly.

“The intercession of a thousand small sanities”, as Gopnik so elegantly puts it, will never be a popular approach to coping with complex predicaments, especially as they grow, through the indifference and incompetence of leaders and vested interests and the sheer size and scale of the systems creating them, into crises and then into chaos and collapse. Yet it is the only approach which has a chance of making things better.

And this is the reason, I think, why more and more informed, intelligent, imaginative people are giving up on trying to ‘reform’ our systems through various complicated solutions, and joining the ranks of the ‘collapsniks’ who concur with John Gray’s analysis that our civilization and our world cannot be “saved”, and that instead of hoping and trying to save it we should do nothing more than becoming more our animal selves — reconnecting with the rest of life on Earth and with our primeval senses and instincts, getting outside our heads, coping with contingencies (perhaps through “the intercession of a thousand small sanities”), relearning to play, living in the moment, turning back to real, mortal things, and simply seeing what is.

This seems to me obvious in hindsight, but it has taken me a decade of study and learning and reflection to realize (and I have been so privileged to have had the opportunity to learn it)! What may now be labeled as fatalistic, pessimistic, hope-less “doomer porn” might, soon enough, come to be seen as just a modest and enlightened philosophy of how to live a better life.

But “simply seeing what is” seems so difficult! Setting aside, or moving beyond, our conditioned thoughts, our acculturated worldviews, has been part of the common wisdom of the sages–yet, in my case at least, it sure doesn’t come easily. (For example, while I agree that we cannot save civilization, I still find myself feeling guilty about not following my friends in their forced optimism and in their reform campaigns.)

Pingback: The intercession of a thousand small sanities… « UKIAH BLOG

hiya … I agree with you …

for me I put it differently … in that I think people can change how they socialise … from the current model which is based on fitting in and following others … to one based on managing our own thoughts. For example I have written down the 9 GOOD traits I follow and 5 BAD traits I try hard to avoid at Respectexchange.com

hope this adds …

Paul: I’m in the same boat. I keep wondering if “just being” is “naturally” so hard, or if our culture has made it so hard (both by social pressure and by the learning we’ve been inculcated with since childhood, to the point it has affected the way the neural paths in our brains have developed). I’m trying to let go — of my expectations and judgements, of my reactions to others expectations and judgements of me, of everything that keeps me from being able to really see what’s going on in the world. It is a lifelong practice, but I’ve reached the point that I can no longer follow any of the established, accepted, “normal” paths. Even though I have not yet found another path, and possibly never will.

Pingback: 16. READ. LOOK. THINK. | Jessica Stanley.