Trust is an essential requirement for an effective, functional community. Our modern, anonymous neighbourhoods provide none of the prerequisites for trust, and hence can never be true communities. In our search for community, many of us reach out instead to those outside our neighbourhoods, looking for support, or reassurance, or knowledge, or partners, or just company. But what is it that makes us trust, or distrust, someone? Is trust something that must be earned, or is it implicit, and can only be destroyed and lost?

Trust is an essential requirement for an effective, functional community. Our modern, anonymous neighbourhoods provide none of the prerequisites for trust, and hence can never be true communities. In our search for community, many of us reach out instead to those outside our neighbourhoods, looking for support, or reassurance, or knowledge, or partners, or just company. But what is it that makes us trust, or distrust, someone? Is trust something that must be earned, or is it implicit, and can only be destroyed and lost?

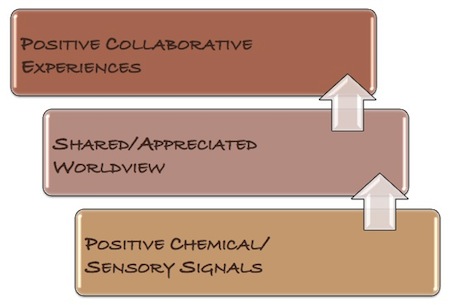

Much has been written lately on this subject. Many would argue that trust is something that grows with mutual knowledge, openness, and sharing. I think that’s true to some extent but I believe trust is much more primal than that. It surely predated language. It is evident in non-humans who do not use language as we do, and whose social networks are not established the way ours are. Watch two dogs meeting for the first time and you’ll see what underlies the establishment and building or destruction of trust. We are, after all, much more than our minds, and our minds, I would argue, play a relatively minor role in the establishment of trust. Here’s how I think it works, based on my own observation of creatures human and non:

- As Keith Johnstone explains in Impro, when we first meet someone, before a word is spoken, our whole bodies are sending and receiving signals, largely unconsciously, to and from the other person. Our processing of those signals is also largely unconscious, as our conscious minds generally tend to rationalize and/or second-guess, rather than create, our immediate impression of another person, including their trustworthiness. This is an obvious evolutionary process: Facing an unknown creature in the wild, having to rely on our slow thought processes, or on conversation with them, could prove fatal. Instead we use sensory and chemical clues: Eye movements, facial expressions, pheromones and other chemical signals, whole-body stances, postures and movements, and tone of voice. When we “meet” someone virtually, online, we struggle with the shortage of such clues, over-relying on the few that are available, and trying to suspend judgement until we have more.

- Once these chemical and sensory signals have been processed, we can build (or destroy) trust through getting to know them intellectually. In this second stage of trust-building, what we are seeking, I think, is either a shared worldview, or alternatively one that we can appreciate (i.e. understand it well enough to have a sense of (a) what the other person thinks is “true”, and why s/he thinks so, (b) what principles the other person believes in (what is “good” or “fair”), and (c) as a consequence, what that person is likely to do in any given situation. Once we think we know how someone will behave in a situation, we can trust them — they are unlikely to surprise us. What’s important is not agreeing with their actions but “knowing” them well enough to predict those actions.

- A third level of trust-building occurs when our instinctive/sensory/chemical sense of someone’s trustworthiness, and our intellectual knowledge/appreciation of them, is tested through actual collaboration — shared experiences, especially of mutual reliance or co-dependence. If their actions during these experiences conform with our positive intuitive and intellectual expectations, there is likely to be a strong bond of trust formed, as all three types of “evidence” indicate the person is trustworthy. I would argue that if there is an absence of sensory/chemical or intellectual basis for trust, positive collaborative experiences alone will not be enough — there will be lingering doubts about what motivated the other’s behaviour in these experiences (a desire just to please, or to create a false sense of confidence, for example).

The destruction of trust can occur the same way, except in reverse. Have some bad collaborative experiences with someone you thought you knew and could trust, and you’ll be suspicious and disappointed, but still probably have faith that it was an aberration — after all, your instincts have told you they’re trustworthy, and you think you “know” them well enough to believe they wouldn’t normally do that. You’ll probably give them another chance, and only if you’re disappointed again will you conclude you didn’t really know them as well as you thought, and that they can’t be trusted.

Likewise, if you get into a discussion or situation that reveals that that person’s worldview — their sense of what is, and why it is that way, or their sense of what’s good or fair, is very different from what you supposed, and you’ll suspect they’re facile, or erratic, or dishonest, or even psychotic, and whatever trust you might have built between you will be destroyed.

If something should occur that changes the basic sensory or chemical signals you give off to that other person, or they send to you, then the degree of intellectual appreciation and positive shared experience you have between you can quickly become moot. You may never know what happened — it may be something that happened to you that has nothing to do with the other person, or vice versa — but somehow you just “know” that the trust you built between you is gone, and rebuilding it, through no one’s fault, will be enormously difficult.

That’s my sense of what underlies, builds and destroys trust, anyway. I tend to be more tuned in to my instincts than most people, and to trust them more than most, so perhaps my perceptions of trust are different from others’. But trust is so important, and will become much more so as we face mounting crises in the coming decades that will require us to re-create local community and to trust those in our communities. We need to know what that will entail, and the challenges building trust will present.

Mr. Pollard:

Excellent article. This trust topic is one I am passionate about. We have spent years developing open standards for capturing and measuring Relationship Capital (RC). In business, it can be to risky to trust too much or too little. We believe the quality of relationship measurements should be neutral ground and not owned by for-profit businesses such as Facebook, Google, etc.

In this hyperconnected and technology-enabled world, our vision is that the individuals, organizations, and products/services that earn and account for their Relationship Capital (RC) will achieve greater success than those who do not.

This has always been the case offline.

Now we can take the offline social networking advantage and apply it to the online social business world.

-Rob Peters

Founder – Standard of Trust

Thanks. We need more conversations about givers and takers. I was talking to a friend yesterday about how easy it is to get to know someone on a camping trip. Character is defined by what they bring to share, how they choose to pitch in with the chores, and whether they return that pile jacket you loaned them. The takers have many names; the resource extractors, the r-strategists, the colonizers, the capitalists.

Pingback: E L S U A ~ A KM Blog Thinking Outside The Inbox by Luis Suarez » Restoring the Human in Humanity by Simon Sinek

Pingback: Dave Pollard: What Makes Us Trust Someone… « UKIAH BLOG

Hi,

I found it interesting that two of my favorite bloggers, Dave and Miki Kashtan, posted entries on trust this week. I though it might be edifying to Dave’s readers (and Miki’s) to cross-fertilize by given you the link to Miki’s blog. She is a trainer of Nonviolent Communicating with I also practice and teach. This gives her a little different perspective than Dave’s.

Here’s the link: http://baynvc.blogspot.com/2012/08/some-thoughts-about-trust.html

Peace n Love,

David McCain

This is a rather wonderful analysis of the basis for trust, for building it, and for losing it. It is methodically laid out, the sort of thing that could be passed along if I were fortunate enough to have a child of my own. The basis for trust is both non-tangibly signaled and based on tangible criteria e.g. facts, reliability and validation due to familiarity. Yes!

Here’s where I have trouble: It is rare to find individuals who have similar world views as oneself about everything. I accept that! Yet I don’t find many other people who do, with one exception: when using Twitter, or Identica. It is unique to Twitter, and the aspect that makes so fond of it. I wish this were not so rare, for me to find people who will trust me based on our commonality, rather than causing the areas of dissonance to prevent any trust at all.