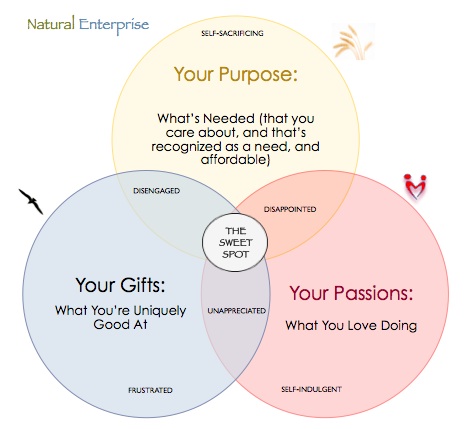

illustration from my book Finding the Sweet Spot

Robert Reich, the reformed former US Labor Secretary (under Clinton), recently wrote a very short summary explaining how the globalized, corporatized so-called “free market” economy benefits only a very few. I’m reproducing it below in its entirety, to set the stage for some of my thoughts on why real, grass-roots, local collaborative enterprises and co-ops are suffering so badly even as this economy continues to collapse:

One of the most deceptive ideas continuously sounded by the Right (and its fathomless think tanks and media outlets) is that the “free market” is natural and inevitable, existing outside and beyond government. So whatever inequality or insecurity it generates is beyond our control. And whatever ways we might seek to reduce inequality or insecurity — to make the economy work for us — are unwarranted constraints on the market’s freedom, and will inevitably go wrong.

By this view, if some people aren’t paid enough to live on, the market has determined they aren’t worth enough. If others rake in billions, they must be worth it. If millions of Americans remain unemployed or their paychecks are shrinking or they work two or three part-time jobs with no idea what they’ll earn next month or next week, that’s too bad; it’s just the outcome of the market.

According to this logic, government shouldn’t intrude through minimum wages, high taxes on top earners, public spending to get people back to work, regulations on business, or anything else, because the “free market” knows best.

In reality, the “free market” is a bunch of rules about

- what can be owned and traded (the genome? slaves? nuclear materials? babies? votes?);

- on what terms (equal access to the internet? the right to organize unions? corporate monopolies? the length of patent protections? );

- under what conditions (poisonous drugs? unsafe foods? deceptive Ponzi schemes? uninsured derivatives? dangerous workplaces?);

- what’s private and what’s public (police? roads? clean air and clean water? healthcare? good schools? parks and playgrounds?); [and]

- how to pay for what (taxes, user fees, individual pricing?). And so on.

These rules don’t exist in nature; they are human creations. Governments don’t “intrude” on free markets; governments organize and maintain them. Markets aren’t “free” of rules; the rules define them.

The interesting question is what the rules should seek to achieve. They can be designed to maximize efficiency (given the current distribution of resources), or growth (depending on what we’re willing to sacrifice to obtain that growth), or fairness (depending on our ideas about a decent society). Or some combination of all three — which aren’t necessarily in competition with one another. Evidence suggests, for example, that if prosperity were more widely shared, we’d have faster growth.

The rules can even be designed to entrench and enhance the wealth of a few at the top, and keep almost everyone else comparatively poor and economically insecure.

Which brings us to the central political question: Who should decide on the rules, and their major purpose? If our democracy was working as it should, presumably our elected representatives, agency heads, and courts would be making the rules roughly according to what most of us want the rules to be. The economy would be working for us.

Instead, the rules are being made mainly by those with the power and resources to buy the politicians, regulatory heads, and even the courts (and the lawyers who appear before them). As income and wealth have concentrated at the top, so has political clout. And the most important clout is determining the rules of the game.

Not incidentally, these are the same people who want you and most others to believe in the fiction of an immutable “free market.”

If we want to reduce the savage inequalities and insecurities that are now undermining our economy and democracy, we shouldn’t be deterred by the myth of the “free market.” We can make the economy work for us, rather than for only a few at the top. But in order to change the rules, we must exert the power that is supposed to be ours.

Mr Reich may believe in the ability of the political system to change the “rules” to adopt an economy that “works for us” (though I’m dubious; he’s worked in the system long enough to know better). I, however, don’t. The mess we’re in is nobody’s “fault” — it’s the result of people using their power and influence in their personal self-interest, which is exactly how this system is supposed to “work”, the only way a large-scale political or economic system driven by money really can.

It’s also, in my opinion, beyond repair or reform. Instead of hoping to fix it, we should, I believe, start to acknowledge it, understand it, and adapt to it. I think the best way to do that is to start by looking at and accepting the facts about our dysfunctional global industrial economy in the 21st century. They’re pretty grim. Here are a few of them:

- Skyrocketing Gini Index of inequality and disappearance of the middle class. 400 Americans now have the same combined wealth as that of the poorest 50% of US citizens. That means almost all ‘discretionary’ and luxury spending (which is half of all spending) in the US is done by a tiny number of Americans. It’s better in Canada but trending quickly in the same direction.

- Large corporations pay very high wages to executives and select contractors (e.g. lawyers), meagre wages to everyone else, and are cutting staff, services and contractors to keep profits growing.

- The real rate of inflation is at least 8%, not what is published by governments. For example, a prescription that cost $200/month seven years ago probably costs at least $400/month now. That rate is much higher than the rate of interest people’s pension money is yielding and far higher than wage growth for the 99%. And many benefits once given to line employees (e.g. defined-benefit pensions, automobiles, prescription and dental plans) have been eliminated entirely.

- Market share, media clout, intellectual property laws and accumulated wealth collectively allow large corporations to dominate every industry. These oligopolies ‘buy’ tax breaks, subsidies, and regulatory reductions from politicians. This gives them a huge competitive advantage over small enterprises, and allows them to buy up or crush innovative competitors (which are usually small and cash-poor).

- The executive class work crazy hours, and mostly pay people to do stuff for them. The working class also work crazy hours at multiple jobs, and usually have no time or money for anything beyond survival and needs of the moment (cheap food, beer, escapist entertainment). The middle class were the only ones who had both money and the time to spend it on non-urgent things. So while established business-to-large-corporation products and services, luxury consumer goods makers and do-it-for-executives personal services are thriving, almost all other types of enterprises are struggling.

What does this mean if you’re working with a small enterprise or co-op, or hoping/planning to start one?

Pollard’s Law of Human Behaviour says: people do what they must (what’s urgent in their own personal day-to-day priorities), then they do what’s easy, and then they do what’s fun. They have no time or energy (or money) left for what’s ‘merely’ important to them or good for them. Because non-executive customers’ spending power has decreased dramatically (and these customers are working longer and harder just to keep up) sales to these customers, the mainstay of most small enterprises and co-ops, have shrunk significantly, and there’s been downward pressure on prices as well.

In short, as the middle class has disappeared, so has the capacity of citizens to buy the goods and services that are mostly provided by small, local enterprises and co-ops. It’s the Wal-Mart Dilemma writ large — people who work for companies that pay slave labour wages can only afford the cheap, shoddy merchandise (including junk food) that similar wage slavery corporations sell.

So if you don’t want to get swallowed up in an economy that makes you work longer and harder for less and less, what can you do?

The first step, I think, is to wean yourself off the global industrial growth economy as much as possible, so you’re not contributing to the problem. That means giving up junk food, buying at the mall, investments in the big banks and in public corporations, indebtedness to the usurers, especially banks, big mortgage companies and credit card companies, and paying for canned entertainment of all kinds. It means needing less, by learning to make and do more yourself (personally and in community). It means buying used. It means valuing your time more and money less.

It means doing things together with others that don’t cost money. It means ceasing to be a passive consumer. It means buying local. It means sharing. It means living simpler. It may mean getting your expenses down and your lifestyle shifted to the point you can quit your wage slave or large-corporation job and start to make a living for yourself with others in your community, meeting real local needs.

The second step is connecting with your community, rediscovering it as a shared place with an ever-growing ‘commons’ — resources and places — that you agree to contribute to, share and co-manage. And learning new skills, hard and soft, that will make you a valuable, trusted and loved member of that community. Pretty soon, you’ll know the community well enough to start to understand what they need that is no longer being provided by the crumbling industrial growth economy (or never was) that’s in your ‘sweet spot’ — something that you and partners with complementary skills can provide that you’re very good at, and love doing, your ‘right livelihood’.

Of course, it’s not that easy. We have lost our sense of community, and our willingness to build and associate and collaborate with people in our physical vicinity, some of whom we may not particularly like. Many of these essential capacities will take lifetimes and generations to become competent at again. And as long as the dregs of the industrial growth economy keep dumping cheap junk from the latest wage slave nation on us, many will be tempted to take them and worry about tomorrow, tomorrow.

But even if we can re-create community and tap into what we really need for a responsible, sustainable and joyful life, what do we do if the goods or services we provide aren’t affordable to, or aren’t yet appreciated by, those who need them? In other words, what do you do when you’re in the business of providing services that are not urgent, easy or fun, mostly for a middle class that has become working class and now has very little time or money for ‘non-essentials’? How can you make what you do essential and affordable to those who need it?

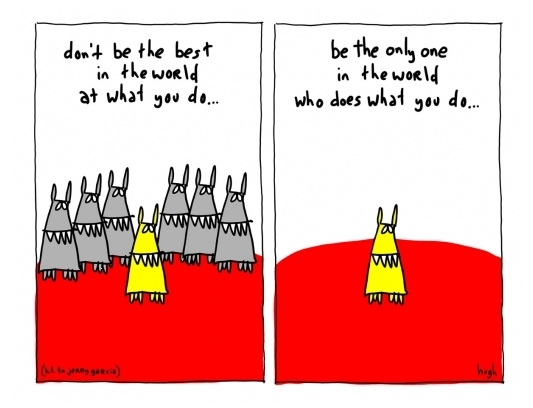

cartoon by hugh mcleod at gapingvoid

Here are a few ideas:

- Combine it with related or alternative offerings of others, so that you collectively make it easier and less time-consuming for people to get what you offer. You may be able to achieve some cost economies in the process that can be passed along to your customers. This is the advantage that led to the development of shopping ‘malls’, and Saturday farmers’ markets.

- Understand and stress the benefits of what you do. People don’t buy things for their features; they buy for what those things do for them, things they think are important. People don’t buy a drill, they buy (a solution to provide) the holes they need drilled. People eat fast food to save time and energy, not (usually) because it tastes good. If you sell ‘slow food’, for example, how might you make it ‘faster’ without compromising quality? Offer to chop or mix it for the customer at point-of-sale? Offer easy recipes and provide a kit with all the (fresh) ingredients? And while you’re at it, provide the customer with hard data that shows how many days eating well adds to your life, and how many more of those days will be healthy. And no matter what product or service you provide, the fact that you, the supplier, are local, not ten thousand miles away, and that hence you are accessible, knowledgeable, and committed to the community in which you and your customers live, is a huge benefit.

- Talk with people who you think need what you offer but aren’t buying, and find out why not, and adjust what you offer accordingly. The people you ask will probably want to make you happy with excuses, but persevere and find out the real reasons. In the process of doing this:

- Discover what people really need through collaborative, iterative conversations. Most people don’t really know what they want. They need to be talked through it, to discover it with you. No one thought they ‘needed’ to be able to keep and play all their music on a handheld device. Until they realized it could save them a ton of money, enable them to share their collection, and increase its durability, and until they appreciated that the initial challenges of poor headphones, expensive digital storage, compression and processing speeds were all solvable. Now most of us would be lost without these inexpensive, ubiquitous tools. Appreciation of needs and ideas to address them co-evolve, and conversations are the best way to fast-track that evolution.

- Find imaginative partners. We live in an age of great creativity (making beautiful, intricate things once they’ve been invented and spec’d out), but terrible imaginative poverty. The kind of person who reads about why butterflies are so colourful when their wings have no pigment (hint: it’s molecular light refraction), and then realizes that this knowledge could be used to create un-counterfeitable currency or colourful paint-free products, is worth their weight in gold.

- Make using your product or service more fun. We have become passive consumers of absurdly overpriced canned entertainment, and have forgotten how to create fun for ourselves. Show us how to do it.

- Be unique. As the cartoon business card above says, don’t try to make a living doing something incrementally different from what others are doing. Any ‘competitive advantage’ of being cheaper or faster or ‘better’ than others is inevitably transient. Be the only game in town, even though it takes a lot of work and thought to do it. And if you succeed, be sure that others will try to copy you with their own incremental differences. But the advantage of having been there first is enormous.

- Capitalize on the sharing economy. What do the people in your community own that they rarely use (think: spare bedrooms, second cars, tools and toolrooms, formal wear, fruit trees), and how could you connect those people with others who could really use these ‘surplus’ goods? Who has skills and time on their hands (think: retired people, unemployed people, disadvantaged people) that could be put to good use meeting real needs? But don’t think about how this can be money-making; think about connecting the surplus to the needs, and trust that the joy of the givers and the gratefulness of the recipients will ultimately provide you with rewards different and greater than you could imagine.

- Give it away free, and freely. Our gifts have a remarkable way of coming back to us in surprising ways (just as our harmful acts do). Humans are essentially generous and appreciative, and as Charles Eisenstein and others have been explaining the Gift Economy is the natural economy, the one that we have lived with for most of our time on Earth. Our stingy, selfish, dysfunctional, price-driven industrial economy may make you feel foolish for giving things away without thought of reciprocation or recognition (‘charitable giving’ is not giving things away, and is never ‘free’), but try it; you may be amazed.

- Be patient. Most people who have found their ‘sweet spot’ have many stories of earlier failure. Fail fast, intelligently and inexpensively, learn from your mistakes, and try again. The work you’re meant to do is waiting for you to discover.

So Mr Reich is correct — we need an economy that works for us, not for the 1%. But the best way to create that economy is not through lobbying or voting or protests, but by working together in our communities to meet our own needs, intelligently, sustainably, responsibly, imaginatively, and joyfully.

It will not be easy, but its time is coming, fast.

Excellent piece, Mr. Pollard. I think we agree that the status quo and the barriers to change are largely rooted in features of human nature such as the bias towards immediate vs long-term risk aversion. In addition to the good approaches you mention, I would stress the emerging sciences of neuroeconomics and behavioral economics.

I was glad you mentioned malls and farmers markets since I think a promising framework for locally-biased cooperative self-development would be a “green mall”–a cooperative umbrella and incubator for smaller coops and other green enterprises.

Perhaps above all, as critical thinkers and writers, we could identify and publicize actual case studies of notable failures as well as success stories.

Pingback: Education | Pearltrees