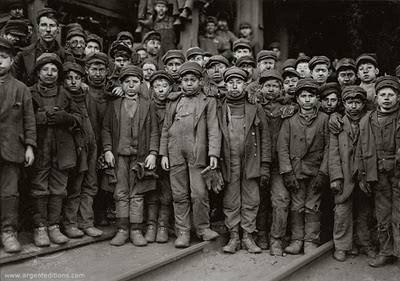

child labourers, Pennsylvania, 1910, photo by Lewis Hine in the National Archives

The word “work” originally meant “what we do”, and came into use around 900 years ago. At that time it was mostly about craftwork, and the design and creation of art. The words “job” and “employee”, describing modern forms of voluntary servitude, are only about 170 years old, inventions of the industrial age. Prior to that, there was of course, involuntary servitude, in the form of slavery, feudal serfdom, and military conscription, dating back about 4,000 years.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the bicameral mind, the evolution in the human brain that makes possible the conception of the separate self, and of language, agriculture and “civilized” culture, is also believed to date back about 4,000 years. As soon as there were creatures who conceived themselves as separate beings with free will and choice, there were other creatures poised to exploit that sense, and the anxiety that accompanied it, to bend them to obey another’s will. Hence armies, hierarchies, nobles, serfdom, and the use, and abuse, of power.

The vast majority of us today spend roughly half our waking hours directly or indirectly engaged in “work”, and before that being “schooled” for “work”, from very early childhood until death, or, for a lucky few, until we are deemed unsuitable to continue working and are “retired” from the work “force” and labour “force” (one of many “work”-related terms borrowed from the military).

It is perhaps surprising then, this invention of voluntary servitude called “work” being so new and yet so preoccupying our lives, that relatively few of us even ponder the purpose of “work”, and most just assume this exhausting and life-defining labour is essential to society’s functioning.

It’s a false assumption. Even with our unsustainable human numbers, the availability of billions of barrels of oil, each capable of producing the equivalent of 4.5 person-years of labour, is more than enough, if it were not spent on wars and extravagances, and if it were even close to equitably distributed, to allow everyone who didn’t want to work to live a life of comfortable leisure. In fact, this bonanza of essentially free energy has both enabled and provoked the hockey-stick exponential growth of human numbers, from less than one billion when it was first discovered (and when the concepts of “jobs” and “employees” were first invented), to nearly eight billion today.

As Daniel Quinn has explained, it is the availability of food (and the productive capacity to make it available in vast quantities that cheap energy has enabled) that has led to the population boom. In all animal populations, even in creatures as bone-headed and disconnected from the rest of life as our species, numbers adapt quickly to the availability of food.

So one reason we feel we “have” to work is because the number of humans we have to feed quickly explodes to match the amount of food we produce, necessitating ever more work to produce ever more food and other necessities of life for ever more people — and because the wealth is so inequitably distributed and so much of the wealth is squandered on non-necessities, the system is in a state of constant scarcity.

Yet even with this massive waste and inequality, the vast majority of “workers” — and “executives” in particular — are employed in completely unnecessary bullshit jobs. The economy employs people not because it has to (a comfortable guaranteed annual income would be a much simpler and more effective way to distribute wealth) but because it feels it must do so to enable the species to have the means to buy the insanely overpriced and mostly useless shoddy crap that has to be sold “to keep the economy growing”. It’s an insane mass delusion, and we have all been conned into believing it, and have spread this nonsense propaganda to our children.

And to keep the mad wheel spinning, a comparable, extravagantly-expensive barrage of propaganda called “marketing” is required to convince us that we “need” to buy this crap, that our very identity is caught up in how elegantly we decorate our homes and our bodies.

And of course, it’s killing the planet. But this system of mostly-useless “work”, of excessive production and subsequent trashing of mostly-worthless overpriced junk, has been operating for 170 years, as long as the idea of “work” and “industry” has been around, since there were only a billion of us living mostly within our means. And like all complex systems, it obeys Pollard’s Law of Complexity, which means it will continue to resist reform and try to self-perpetuate until it can no longer do so, and then rapidly collapse.

For almost all of us, while it may seem that our work has purpose and meaning, it is completely unnecessary, a product of a completely dysfunctional economic system. Were it not so, the only people who would “have” to “work” would be those who find joy in making things work well and making them work better.

This was the original meaning, and value, of “work” — the work of the crafter, the artist, and more recently the scientist, those pursuing their passion to make the world a better place. This true work is about making an essential product or service better. Not the bullshit jobs of ad agencies, sales “forces”, usurious bankers, munitions manufacturers, vulture capitalists, f&%^ing lawyers, factory farm managers, commodities speculators and other highly-paid miscreants.

As our economy gets more and more dysfunctional in its more advanced state of collapse, it will serve fewer and fewer of us, and, as happens in all civilizations, the vast majority of us will, one person at a time, walk away from it. We will, by force or by choice, stop buying what we don’t need, refuse to pay for what is essential (recognizing that the bounty of the world belongs to all of us, and should be distributed generously and freely to all), and — most importantly — refuse to work. It can’t happen soon enough. As quickly as economic collapse often unfolds, because of Pollard’s Law it will need to be precipitated; we should strive to accelerate collapse before it exhausts the last of the planet’s resources.

In the meantime, there is real work to be done. In the vacuum of collapse we will have to relearn how to build real community, and all of the skills and practices that making a life in a radically relocalized community entails, like those described in this list:

And as we start to do that, we can learn about deep work, the work of inventors, artists, craftspeople, scientists and others whose energies are actually spent in making things work well and making them work better.

This real work, I believe, has a number of characteristics:

- It is extraordinarily collaborative and deliberative. As with the thousands of public health workers all over the world who have struggled with understanding and coping with CoVid-19, this is not siloed work, and nothing is kept secret. It has no individual heroes. It’s the future of our planet and our societies that’s at stake, and only by standing on the shoulders of giants, and standing shoulder-to-shoulder with others with different knowledge, ideas and insights, can this work be done well.

- It is unashamedly generous. It is done for its own sake, because it’s important, because it cannot not be done, not for profit or glory.

- It is painstaking and patient. Real work requires concentration, experience from failure, years of practice, perseverance, and self-discipline. If it’s rushed or done sloppily or thoughtlessly or distractedly, it’s not good work.

- It is both imaginative and creative. These are different qualities, and they require different innate and practiced capacities. We live in a world of enormous imaginative poverty because we no longer practice it, as children or as “employees”. And we abuse the term “creative” to describe worthless financial “products”, incremental, derivative thinking, marketing “buzz” and too much other useless “work”.

- It stems from a combination of passion and curiosity. We can only do real work when we really care about the world and how what we do contributes to making it better. And we can only make things better when we’re curious about why they are the way they are, and capable of pursuing “what if” lines of thinking.

- It requires exceptional critical thinking skill. That requires great humility. It is easy to produce a new design, a new theory, a new idea. To understand why things are the way they are, and not how one wishes or hopes or thinks they might be, is to realize how insignificant and powerless we are, as human individuals. Critical thinking requires both a conscious process (built on self-knowledge and self-awareness of one’s own ignorance, biases, and poor thinking and behavioural habits), and years of practice.

- It requires enormous attention and listening skills. There is a horrifying shortage of these skills in modern society, and especially in most modern “work” places.

One of the things that most shocked me when I retired was the realization that, after 37 years in the work “force”, I had really done almost no real work. And the little real work I had done was almost entirely outside the “work” place, and almost entirely unpaid.

Since retiring, I have basically gone back to square one — learning more about myself and building personal core capacities (the first four steps in the Being Adaptable list above), and practicing doing things that I care about (in my case writing, conversation, music, and learning) and things that I’m at least marginally skilled at (making unique connections between ideas and information from disparate fields, and using them to imagine new possibilities).

I live in a community that has real needs — lots of old people, many single and in not-great health, so when the power goes out or the driveways get snowed in, or there’s a medical or plumbing emergency, or a scary intruder, or a fallen tree, or the ferry is cancelled, or any of a hundred other little crises that can happen in an isolated community, people need to get working on them fast. And I have realized that I have essentially none of the skills that my neighbours might need. For all my lauded successes in the “work” “force”, my exceptional reputation, and all the praise and thanks I’ve been given for my “work”, I’m more or less useless here.

Most of us are going to find that, as economic collapse deepens and becomes permanent, and then ecological collapse weighs in, most or all of the “work” we’ve done in our careers was actually a waste of time, and of no value in a post-collapse world, leaving us ill-equipped and with little time to relearn what real work is about. It’s going to be humiliating and sobering for many — like the executives — and bewildering for just about all of us.

We’re going to have to figure out what we need, and what our community needs, and offers. We’re going to have to learn some basic skills that weren’t necessary in a hierarchical “work” place. We’re going to have to figure out what our real skills and capacities are, and what we really care about. We’re going to have to discover who we really are and what our biases, fears, strengths and weaknesses, wants and needs, triggers and sorrows are, and for many that will be a horrifyingly difficult and sobering process.

Only then can the real work begin.

I think that the importance of any kind of work is roughly inversely proportional to where its product falls on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Work directly related to the production of food, water, and shelter is therefore far more important than work related to self-actualization. The collapse of industrial civilization will make everyone’s priorities for work a lot more realistic.

In response to Joe Clarkson’s comment: Interesting thing about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is that he appropriated the concept from the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation’s Breath of Life theory. The shape is a tipi (not a triangle) and actually puts self actualization at the bottom, as the first step.

More info and links at: https://barbarabray.net/2019/03/10/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-and-blackfoot-nation-beliefs/