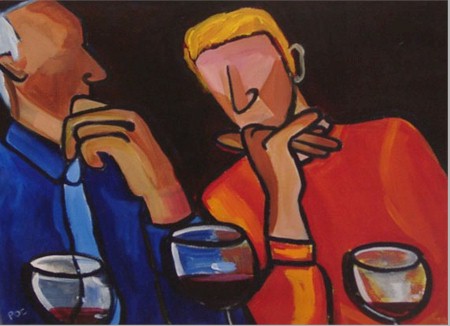

painting “In Deep Conversation” by Irish artist Pam O’Connell

Seven years ago, I wrote a post called Why I Don’t Want to Hear Your Story, describing why bios, OKCupid profiles, and other mostly ‘past-tense’ stories of what you’ve done, are not very interesting. And why likewise, aspirational stories describing what you plan/hope to do in the future (or, in the case of OKCupid profiles, who you hope to do it with), are, to me, mostly uninteresting.

Neither past-tense (historical) nor future-tense (aspirational) stories tell me about who you (think you) are, and what you really care about, right now. That’s what interests me. That’s what I want to talk with you about. We can’t relate that information (presuming we’re even self-aware enough to know it) by telling a story. And since we’re story-tellers by nature, conveying that essential but non-linear information to each other is awkward, unintuitive, and unpracticed.

So in the previous post I suggested six “leading questions” that might evoke some kind of useful sense of who someone is and what they care about, right now, and possibly assess whether the person you’re talking with might be the potential brilliant colleague, life partner, inspiring mentor or new best friend you’ve been looking for. These are the questions:

- What adjectives or nouns would you use to describe yourself that differentiate you from most other people? When and how did these words come to apply to you?

- Describe the most fulfilling day you can imagine, some day that might realistically occur in the next year. Why would it be fulfilling? What are you doing now that might increase its likelihood of happening?

- What do you care about, big picture, right now? What would you mourn if it disappeared? What do you ache to have in your life? What would you work really long and hard to conserve or achieve? How did you come to care about this?

- What is your purpose, right now? Not your role or occupation, but the thing you’re uniquely gifted and inspired to be doing, something the world needs. What would elate you if you achieved it, today, this month, in the next year? What would devastate you if you failed, or didn’t get to try? How did this become your purpose?

- What’s your basic belief about why you, and other humans, exist? Not what you believe is right or important (or what you, or humans ‘should’ do or be), but why you think we are the way we are now, and why you think we evolved to be where we are. It’s an existential question, not a moral one. How did you come to this belief?

- What’s your basic sense of what the next century holds for our planet and our civilization? How do you imagine yourself coping with it? How did you come to this belief?

These are not easy questions, and asking them might prove intimidating or even threatening to some people, which is why in the last post I suggested volunteering your own answer to each question yourself first, in a form such as “Someone asked me the other day… and I told them…”. It’s also why there are supplementary questions to each, to get the person you’re asking started. And the last supplementary question in each group lends itself to telling a story, since that’s what we’re most comfortable with. Even then, some of these questions will stop many people cold, which might tell you something about them right there.

But I don’t think they’re unfair questions, even for the young, though the last two might be a stretch for some. I don’t claim to know my grandchildren well, but I’d be fascinated to hear their answers to these questions. And I’m guessing I’d suddenly know them a lot better than most people in their circles ever have, just for having heard them.

I am rehashing this seven-year-old article for two reasons.

The first is that it’s brought me some realization about what underlies my rather deep-seated and unfortunate misanthropy: I don’t actually like most people very much. Part of that may be that I’m somewhat antisocial by nature; I really do enjoy my own company. But I think the more important part is that I can’t really care about people’s stories — about their past or perceived current situation and their judgements and feelings about them, or about what they hope to do some day. I can care deeply about them, and love them to death, but that has nothing to do with their stories, their “stuff”.

No one can really know what it’s like to be another person, or how they felt or are feeling. And every story is a fiction, just an invention to try to make sense of what we have no choice or control over, so it can never really make sense. I don’t expect you to care about my past or hopeful future story; really, and please think about this if you believe I’m being callous, Why should you, would you, could you care? It’s all a charade, a heavily socially conditioned one, that we should presume to know or care about someone else’s past, or situation, or judgements and feelings about them, or expectations for future change in them. I care about you, now, damn it, and that is all.

The second reason I’m rehashing this article is that since I wrote it just seven years ago (and my situation, my ‘story’ has hardly changed at all since then), my own answers to these six questions (which I volunteered at the end of the earlier article) have completely changed. I am, clearly, not the same person I was seven years ago, and not just because every cell in my body is different.

And one of the things that has changed is that I’m not going to write my ‘new’ answers to the six questions out this time at the end of this post. Though I have given them a lot of thought. And I’d be pleased to talk with anyone about them, on zoom or chat or phone, if you’ve thought about your own answers and are willing to reciprocate.

As long as you promise not to tell me your story.

This post is confusing to me. You are an intelligent and perceptive person (as evidenced by your posts), but you somehow think that people’s stories about themselves, their past, their regrets, their hopes for the future, have no relationship to their personalities in the present?

As you so often note, people are conditioned by the cumulative events in their lives (including the genetic “event” at conception). To me, it would be difficult to relate to someone with any intimacy without a decent understanding of what they had experienced in their past. If I want to get to know someone better, I want to hear their stories, even including stiries about their parents, family and friends. Their stories tell me a lot about what kind of person they are right now.

In many respects, we are our stories. All we are at any moment is our memories (our stories about our past), what our senses are taking in and the way we are feeling. If you are not interested in people’s stories, I can see how you would not be interested in other people. That is indeed unfortunate.

Finally, I noted that your six questions do have a lot of inquiries containing past and future tenses. Maybe you are more interested in people’s stories than you realize or perhaps your post title is more clickbait than reality?

I think most people are interested in other people’s stories, and I’ve certainly told enough of my own. But my sense is that who the person is, really, right now, is if anything actually obfuscated by the stories of their past. We tend to “take on” our stories, as if they were true, and they cover us with gunk that, I suspect, is not who we really are. We have personalities, roles, personas, presumptions about who we assume ourselves to “have become” and who other people have defined us as being. And my sense is that that’s not who we really are at all. But maybe that’s because (1) I’m getting old, and impatient with all that stuff, and (2) the ‘glimpses’ of no-self have persuaded me that we are so much less, AND so much more, than our stories, which now seem to me mostly make-believe. If we are merely our stories, then I fear we may be fictions, which is all our stories can hope to be.

And I really am interested in (some) people, once I can get past their stories. I’ve become aware of the limitations of language and how most creatures forge relationships without any need for language or story. And I didn’t mean the title of the post to be sardonic or provocative; I really mean it sincerely and think there is great potential for us to move beyond past/future stories and establish relationships in a novel way that does not rely on the congruence of our stories.

As for the six questions, I did supplement each with past/future questions to make the six core questions, which are more present-focused, a little easier to get at. But if someone’s answer to question 2, say, is “writing music”, then my interest is not in what they’ve written (history), or what they intend to write (aspiration), but what they’re writing right now and how they’re doing so. That’s what, to me, lends itself to conversation, to discovery, to collaboration, to learning. The rest is just musty tomes and pipedreams.

Hi Dave,

You describe my perception of myself in the finishing passage. It encourages me to enjoy it further. Thanks kindly.

… some realization about what underlies my rather deep-seated and unfortunate misanthropy: I don’t actually like most people very much. Part of that may be that I’m somewhat antisocial by nature; I really do enjoy my own company. But I think the more important part is that I can’t really care about people’s stories — about their past or perceived current situation and their judgements and feelings about them, or about what they hope to do some day. I can care deeply about them, and love them to death, but that has nothing to do with their stories, their “stuff”.

No one can really know what it’s like to be another person, or how they felt or are feeling. And every story is a fiction, just an invention to try to make sense of what we have no choice or control over, so it can never really make sense. I don’t expect you to care about my past or hopeful future story; really, and please think about this if you believe I’m being callous, Why should you, would you, could you care? It’s all a charade, a heavily socially conditioned one, that we should presume to know or care about someone else’s past, or situation, or judgements and feelings about them, or expectations for future change in them. I care about you, now, damn it, and that is all.

Afterthought on this post: I realized after I wrote this that several of the fictional characters in my short stories actually helped me answer these 6 questions. So if you’re trying and struggling to try to answer them, try this:

• If you were writing a novel, and decided to draw on your own character for one of its characters, what adjectives and nouns would describe that character? What would that character care about, mourn the loss of, long for, be really good at, get elated by? What would its worldview be?

I’ve even started wondering whether my passion for writing short stories with quirky characters is my way of ‘getting outside myself’ and seeing myself more objectively from a third-person perspective. My characters are often more playful, freer, more spontaneous, more attentive, and less held back by anxiety than I am, but in some ways they are more ‘me’ than I am.