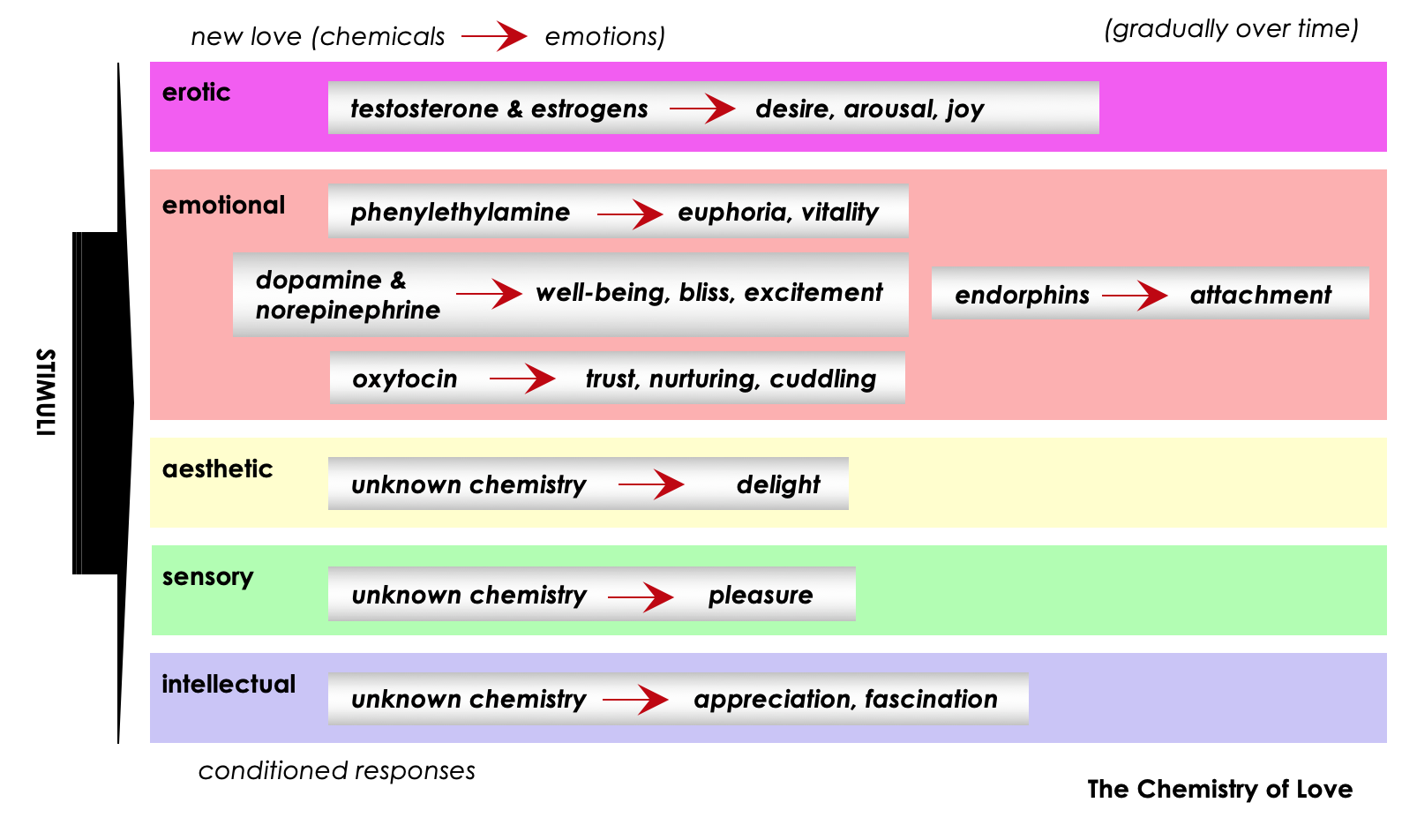

I‘ve been using the chart above for many years, and it’s evolved somewhat, but what it’s basically saying is:

- Everything we call love is a conditioned chemical response to sensory stimuli.

- Nature, in order to propagate the species effectively, hooks us into “falling in love”, deploying a cocktail of powerful chemicals that stimulate us to become emotionally and sexually attracted to the other person. Then, to settle us down for the longer haul, she substitutes endorphins for the more powerful chemicals.

- Emotional love and sexual attraction are prompted by different chemicals, and can often occur independently. Women, for whatever reason, usually seem better able than men to appreciate the difference, and not conflate or confuse the two.

- Other forms of love — our aesthetic love for a work of art, our sensory love of a tropical beach or a forest in the moonlight, and our intellectual love of an idea, model or theory — almost assuredly have concomitant chemical prompters, but nobody seems to know what they are.

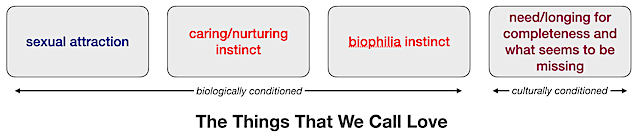

Wild creatures seem prone to the same biologically-conditioned chemical prompts for emotional and sexual attraction as humans, but their emotional attraction is simpler (and probably much healthier) than humans’, drawing on what appear to be almost universal caring and nurturing instincts, and universal biophilia (feelings of love towards all forms of life).

In humans, while we are reacting to the same chemical prompts, our cultural conditioning massively complicates our emotional responses by:

- taking our love-interest’s reciprocal interest in us (or its lack) personally, as if it had something to do with our behaviour or character or appearance, rather than being an irresistible chemical response

- expecting love to fulfil our need or longing for ‘completeness’ and what seems to be missing from our lives

- telling a story about our love, and what it ‘means’

So, when it comes to sexual attraction, and our animal instincts to care for and nurture others, and our innate biophilia, we, and our feelings of love, are, I think, no different from those of many other creatures.

But beyond that, humans seem to feel a need, a longing, a yearning, to fill an empty space within them, to reconnect in a way that, I suspect, other creatures have no need to do. So when we fall in love, and get some brief inkling of what it is like to be really alive, without the false veil of self and separation from everything else, we expect and want that love to fill that empty space “forever after”.

That is an enormous burden to place on a relationship, and on another person, and it is no surprise that sudden, profound feelings of love are so often followed, sooner or later, by feelings of disappointment. For us, sexual attraction and our innate caring and nurturing and biophilia are, somehow, never quite enough (unless we have been conditioned to set our expectations very low).

With the chemicals triggered by falling in love, the sense of self and separation can temporarily diminish, bringing about a fleeting freedom from our enduring feelings of incompleteness (only to roar back if there is jealousy or if the feelings are unrequited).

In a domesticated creature, if there is a lack of healthy attachment (eg if an animal is taken from its mother too soon), or if the creature lacks a sense of autonomy, it might have human-like feelings of neediness, dependence and anxiety, but I’d question whether that’s really love.

With wild creatures (and also when, in a human, there is no sense of self and separation), this neediness and longing appear to be absent, so that biological conditioning (sexual attraction and the caring/nurturing and biophilia instincts) prevail, and cultural conditioning plays a much smaller role.

My sense, then, is that ‘needy’ love, even when two people are able to fill each other’s needs, is rather unhealthy. If our brains weren’t too large for our own good, conjuring up an illusory sense of self, separation and control over ourselves (including control over when and who we love), would we all be like wild creatures, simply and un-judgementally playing out our biological conditioning? Would we then be free of all the anxiety, jealousy, envy, shame and other negative feelings, and the enormous expectations and demands we place on those we love to fill that horrible empty space of incompleteness that we so often carry with us most of our lives?

What I see, sadly, in so many fraught human relationships, is conditional love, and it is conditional upon receiving something from the one(s) we love. Whereas in wild creatures what I see instead (and this is of course only a guess) is unconditional love — love that is free of expectations, judgements, and demands. Love that accepts everyone and everything exactly as it is, as the only way it could possibly be.

When there have been glimpses here when my ‘self’ disappeared, it was this amazing, unconditional love that was seen.

Or at least, that’s how it appeared. But maybe that’s just what this old, idealistic, bewildered, romantic fool — tired of everything seeming so much harder than it instinctively should be, than it needs to be — wants to believe.

Pretty, pretty good. Here – “Other forms of love — our aesthetic love for a work of art, our sensory love of a tropical beach or a forest in the moonlight, and our intellectual love of an idea, model or theory — almost assuredly have concomitant chemical prompters, but nobody seems to know what they are.” I would assert that there are prompters but not necessarily chemical. What prompts the chemicals? We can’t use classical physics (materialism) to define everything.