cartoon by the late New Yorker cartoonist Robert Weber, one of the few cartoonists who worked mostly with charcoal

Every year we hear about workplace surveys that say that most employees are “satisfied” with their jobs, which would, I think, suggest more that they can’t imagine finding better work, than that they like the work they are doing.

We also hear about “quiet quitting”, and complaints that minimum wage jobs are going begging. Employers would like us to believe that that’s because most people are lazy, but if you actually speak to people doing these jobs, it’s quite clear that no one, especially if they have a family, can afford to live on a minimum wage job (or even two minimum wage jobs) with today’s costs of housing, health care, transportation, and other essential expenses that are increasing at twice the rate of the minimum wage and “average” wages.

The truth is that our economy is stretched so tight that there is a huge and growing chasm between what workers need to live even a basically comfortable life, and what dysfunctional corporations desperate to keep profits growing to avoid collapse of their stock prices, can afford to pay them. This is what collapse looks like.

In a recent article, Aurélien explores what this means for the poor beleaguered employee who is spending more than half of their waking hours, for a lifetime, working at, or commuting to and from, a Bullshit Job.

This means accepting, and coming to grips with these terrible realities:

- Employers cannot afford to pay them a decent salary, or give them a decent real-inflation-level salary increase, or give them basic essential employee benefits, or any job security, or the possibility of a decent promotion, or the promise of a pension.

- The level of trust in workplaces is so low that employers dare not let their employees “work at home” or away from supervision, and increasingly use technology to actively disempower employees from providing customers with what they reasonably want and need, for fear that will adversely affect profits.

- Governments, which are mostly now technically bankrupt due to a combination of incompetence, mismanagement, dysfunctional bureaucracy (due to being too big and too centralized), wild overspending on the military and “security”, and obscene tax cuts for the rich and powerful, are trying furiously to reduce and even eliminate essential social services and citizen-protecting regulations to fend off actual bankruptcy. In the process they are aggravating the challenges workers are having trying to make ends meet in their tedious, underpaid Bullshit Jobs.

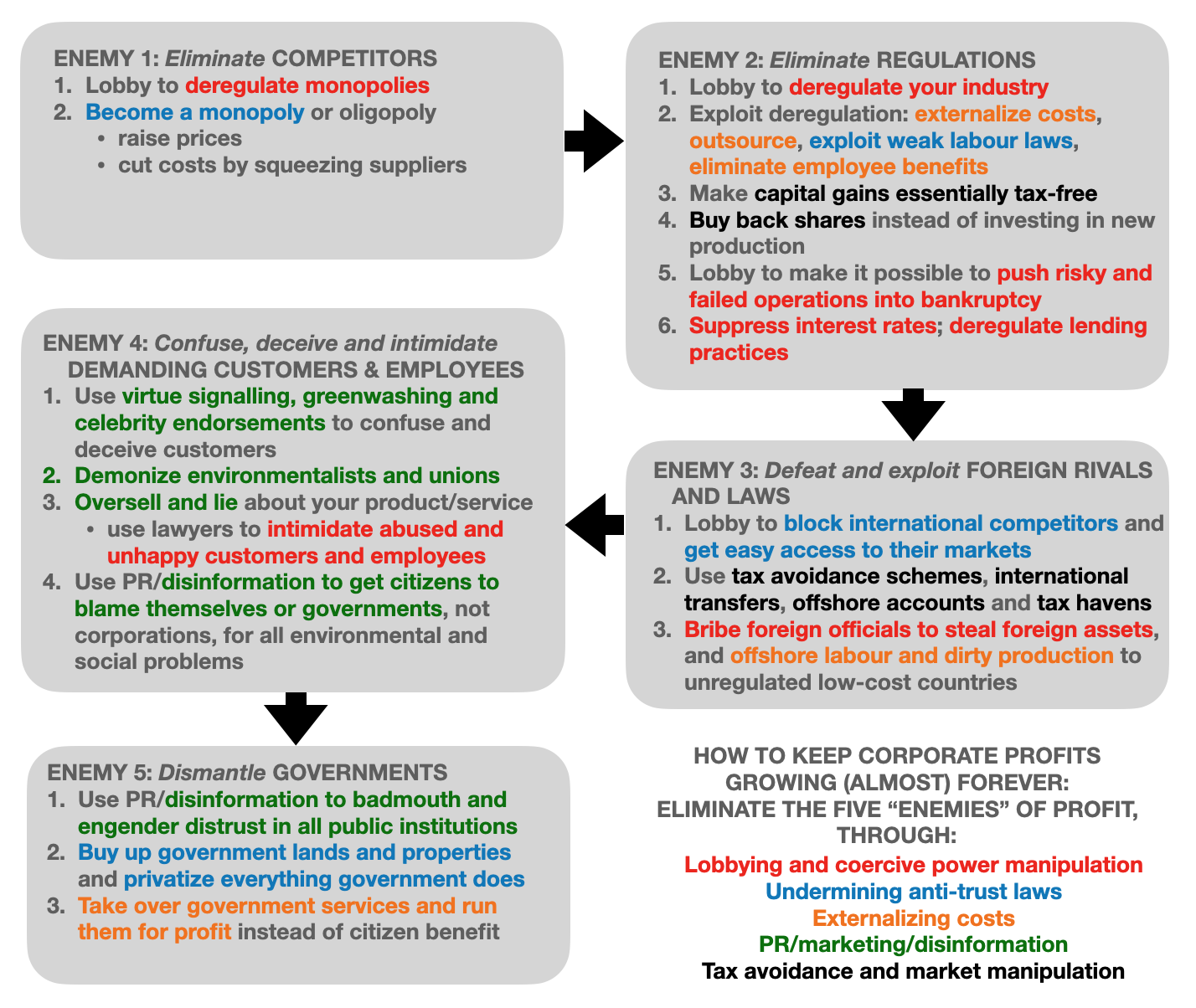

- Corporations (which were actually, as Indrajit Samarajiva has explained, the first form of AI, and remain its most insidious form) are perversely driven by their mandates and charters to try to weaken and replace governments and public services, and to see both their customers (“whiny and litigious”) and their employees (“outsource and offshore”) as loathsome impediments to their profitability and smooth function, and to treat them accordingly.

The fact that anyone is “satisfied” with this state of affairs should be cause for alarm. But that is where we seemingly are.

How corporations’ implicit psychopathy plays out, from my earlier post

Like me, Aurélien is not proffering solutions to this worsening situation. It is up to us, he suggests, to use what power we have to make the best of it. This entails, he says, taking charge of our own work lives, and getting out of the rut of not seeing any alternative to our current daily work drudgery.

What brings joy at work is not, he says, “success”, but rather the satisfaction of knowing that what you do is important — that it matters to, and is appreciated by, customers and co-workers (ie that it’s not really a Bullshit Job), that you have some control over it, and that you know that you and your co-workers are doing good work for the customer, the community, the society, and/or the world as a whole.

Aurélien writes:

I suppose nothing could be more foreign to our present culture than the idea that in life we have a series of free choices, and we are responsible for them and their consequences. In a world where everyone is a victim and no-one is responsible for anything, that’s almost literally heresy. But we then have to ask how practically useful to us, in reality, is today’s ethic of complaint, and futile appeals to “rights.” Does it actually help us to survive and retain our sanity, working in an organisation that hates us? Does it make us happier? I think the answer is obvious.

He goes on to explain how we try to retain our sanity in a brutal workplace, by reference to Jean-Paul Sartre’s and Gabor Maté’s arguments about our fundamental human need for authenticity — our capacity to be honest with ourselves and other about what we believe and want and do, and sometimes what we have to demand:

A very senior official in my organisation once gently explained to me why the extravagant promises of a glittering career made to me when I was younger were now inoperative. ‘Your problem’ he said, not unkindly, ‘is that you’re not perceived as being sufficiently dedicated to the management priorities of the organisation.’ Now as it happened, I was involved in other things than management priorities at the time, and didn’t think about them very much, and rarely if ever said anything about them. Nonetheless, I said, look, I’m a professional, and I do what the organisation wants, including its management practices. Ah, came the reply: but that’s not enough, we need your full-hearted commitment. At that point, I knew it was time to think of going, because once you confuse a bureaucratic organisation with a church or a political party, you’re in deep trouble.

He’s speaking a bit tongue-in-cheek, but I sense a lot of readers will be nodding with recognition of their own situations in dead-end jobs that demand(ed) more from them than they could ever give back.

“Doing a good job” in the face of this, and in the face of dysfunctional organizations, “is an act of resistance” — of defiance even, he asserts.

The large proviso here, of course, is that you foreswear formal protests and open confrontation, and that you care only about the final outcome, not the degree to which your ego is polished thereby. Sometimes there may be no alternative to letting important people with their own large egos make stupid decisions, but there are always ways of quietly unpicking those decisions later, in silence and anonymity.

I think this is brilliantly perceptive, and it resonates strongly with my own experiences through nearly 40 years of exhausting, perplexing, exasperating work. I learned to accept that achieving the right outcome often required letting my boss take the credit for my efforts and insights. I learned to listen to my customers and co-workers and peers, even when I knew that acting on their behalf and against the stated interests or policies of my employer, might be a career-limiting move. It was the right thing to do. I always knew how to do my job better than those ‘superiors’ I had to explain my actions to, who mostly never found out just what I did or how important it really was.

So here’s a toast to everyone dedicated to “doing a good job”, by ignoring all the career advice you received in those cheesy, self-important airport bookstore self-help books, and in spite of the fact everything is falling apart all around us.

It matters, it makes a difference, and it is appreciated in ways you will probably never know. And you probably have more control over your work and your work life than you think, including, if it comes to that, the power to resign. Life’s too long, and too short, to spend so much of it doing work that you’re merely “satisfied” with.

Hmmm, so you seem to like what Aurelien writes about us having “free choices” and responsibility. Is this from the same Dave who has oft written lately about his non-belief in free-will and we do exactly what we are conditioned to do????

Yeah, I put that quote in quite deliberately and a bit mischievously. There is lots of cog diss in believing we have no free will.

I think Aurélien’s point is that lots of people grouse about their jobs and whine that complaining and demanding worker ‘rights’ just alienates bosses and engrains a culture of helplessness. It’s easier to complain and blame the boss for a hopeless work situation than to walk away from it. I really enjoyed doing what I knew was right for the organizations I worked with/for, even when I got hell for it (or would have if I’d been caught). Keeping my job was never so important that I’d deliberate do things I thought were useless or counter-productive.

But then, that’s my conditioning. Once a shit-disturber, always a shit-disturber, I guess. I had no choice in the matter. Nor do the sycophants who will recoil at Aurélien’s advice, I suspect.

But point taken — thanks. Things are never as simple as they appear. And I’m still wavering on whether when you become more self-aware of your conditioning and what it’s compelling you to do, you may actually be changing that conditioning. Which is perilously close to exercising free will, in a way.

I do believe Aurelien talked about the “bullshit jobs” being better paid than the nitty gritty jobs of doing real work, like farming.

It was also interesting to see Aurelien being of two minds… on one hand, advocating doing your work well, on the other reminiscing back to the time when he subtly sabotaged the work he was assigned to do, and felt proud of it.

It’s hard not to be of two minds nowadays… the best we can do, I think, is being honest about it. :-)

Well not every shit-disturber can afford to walk away. Privilege is, I suppose, also a form of conditioning. While I do concede we don’t have “much” choice in Maoist things, I’m not sure if I’m ready to embrace the idea that privilege “is what it is”.

*most*