I‘ve been thinking a lot lately about communities, in the social networking, intentional community and business sense. I was struggling to come up with a model that integrates all these types of communities, and I realized that I would have to come up with a more holistic approach, one not constrained by market-based definitions of relationships. I‘ve been thinking a lot lately about communities, in the social networking, intentional community and business sense. I was struggling to come up with a model that integrates all these types of communities, and I realized that I would have to come up with a more holistic approach, one not constrained by market-based definitions of relationships.

To do so, I began thinking about communities as they function in the gift economy (or as I prefer to call it, the generosity economy). — the growing economy that includes open source, the Internet, scientific knowledge sharing, much foundation and NGO work, blogs, file sharing and a host of other ‘price-less’ exchanges of value. How could we redefine the social constructs of the market economy to suit the framework of the gift economy? Here’s what I came up with:

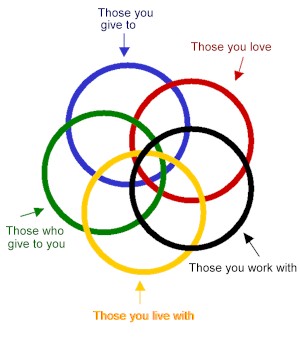

If you use the more inclusive gift/generosity economy constructs, your communities, networks and identities within them merge into these five broad ‘circles’, and the need to distinguish between social and business communities, networks and identities disappears. In a sense this is what is already happening as more of us cease drawing the line between our social and business identities and lives, and as more and more of what we do, powered by the Internet, is done without expectation of financial compensation. This of course is very threatening to the market economy, whose advocates would have you to believe that any activity that cannot be and is not denominated in money terms has no value (and is inevitably inefficient). So, for example, those I give to (my ‘blue’ circle) includes you, my readers, those I coach (my children and grand-daughters as well as those who pay me money for advice), and those who pay me for my expertise during projects, whether in a ‘customer-supplier’ or ’employer-employee’ capacity. Likewise, those who give to me includes those who send me books to review, my electricity supplier, readers who send me e-mails or comments on my blog, other bloggers whose writing I read and value, the grocery store and the neighbours who give us free veggies and fruits from their garden and invite us to dinner. Whether money changes hands in any of these relationships becomes unimportant. Those I work with includes colleagues on various projects from innovation assignments to neighbourhood work bees to those in my fledgling AHA! network. Those I live with includes various degrees of relationship from those who share my house and land (human and other creatures) to the entirety of Gaia, all of us who share this tiny, fragile planet. And those I love is an amorphous group of people and animals and places that is growing at an astronomical rate. There is substantial overlap between these five communities, but I believe they are collectively exhaustive — all of our networks and communities fit within this five-circle model. And this is a model of abundance and not scarcity — if we are generous, there is no limit to the number of people we can invite into any of these circles, and the larger and richer these circles grow, the better off we all become. This takes the concept of the information or knowledge economy as one without constraint or limit to the value that can be given, and expands it to include everything — atoms, bits, and emotions. Using this model, we can define all relationships by their nature (which of the five circles they fit within) and their depth (how much we give, receive and love them, and how closely we live and work with them). And we can define ourselves by the circles of others (which circles and which others) to which we belong. So we might evaluate the nature and depth (scale of 0 to 10) of our relationships like this:

while those who we see ourselves in close relationships with might evaluate them like this:

You may think it fanciful that I’m ascribing conscious and emotional assessments to non-humans, collective groups and even places, but I certainly feel these assessments — I feel my home, the wonderful place where I live (the land, and the diverse and collective life on it) welcoming me when I return to it. Our circles, our communities do not belong to anyone, they are collective. To say these are ‘our’ circles, ‘our’ networks (as social software tries to do) is absurd — it is like saying that because we belong to the human race, or to a political party or other organization, that all of humanity, or all of the party, is somehow ‘ours’ by virtue of our definition of it including us and some ‘others’. The claiming of ‘ownership’ over such circles, such as when we talk about ‘our’ country or ‘our’ party can in fact be dangerous because it oversimplifies and homogenizes the relationship. So how would we diagram these relationships, capturing the nature (which ones of the five circles) and depth of our relationships with others, and their reciprocal sense of their relationships with us? And what about situations where others consider themselves in ‘our’ circles (or us in ‘theirs’) but we do not? We could use arrows of five colours and ten widths pointing in each direction. And we might even use dotted lines to indicate relationships we hope to develop in the future (or which others might hope to develop with us). Very complex, perhaps, and inevitably judgemental and incomplete, but imagine how valuable it might be. And if the de facto communities to which we belong, which sets of mutual links between collections of individuals might portray, define (in a social sense, anyway) who we are, then such a map might in fact be a more accurate and useful portrait of us than anything an artist, photographer, genealogist or DNA scientist could come up with. When someone asks us who we are, how do we usually respond? We say what we do (i.e. define ourselves by those we work with), and/or what company we work for (i.e. define ourselves by those we give to). Or we say who we are related to (i.e. define ourselves by those we live with or love). We sometimes even define ourselves by who gives to us (e.g. when we drive a certain prestige brand of car or wear clothes with a certian logo), the kind of ‘belonging’ that, pathetically, you have to pay for, Another form of this is when we define ourselves by our subject-hood, by the person or group who supports us (father-figure, cult leader, religion or citizenship). How you answer this question (“I’m a consultant. I’m an analyst at Microsoft. I’m the person assigned to your account. I’m the son of X. I’m Mrs. Y. I’m Amanda’s father. I’m a member of Z. I’m a Welshman.”) may say a lot about which circles are most important to us and which we feel we belong most to. In fact we have multiple identities and we may answer that questions in the context of who is asking (which of the five circles they are probing for) — If the question comes from Amanda’s best friend’s mother, I’m more likely to say I’m Amanda’s father than to say I’m an accountant. Assuming we could develop such maps (maybe we need some way to link stories about each of our relationships to give them context and verifiability), how could we use them?

An application of all this that intrigues me is in assessing how we should (and can) change ourselves. I tend to agree with many of you that if we are to have any credibility as change advocates we need to be a role model, we need to show not tell people what needs to be done. We need to be the change. So do we start by a navel-gazing process that entails some personal, individual decisions and bold actions? Or, if our relationships and networks define us, do we start by first finding or redefining the circles, the communities to which we (and others) belong and then let those new and altered communities redefine and change us? For example, if we want to solve global warming or end world poverty do we first launch into personal study, self-improvement and individual activism, or do we first connect ourselves with those who can teach us and show us what needs to be done, and just get carried along with the collective wisdom of their activities? Could the map tell us what to do? |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

A terrific post, Dave! I love both the simplicty & complexity of the map of overlapping circles.Coincidentally, I was trying to imagine recently what it would/might have been like if I had consciously asked for help in making myself over in my 20’s and 30’s. I realized immediately that the main obstacle was my need to feel in control already, and my inability to trust others with areas where I felt vulnerable. Still, I did benefit from suggestions from friends who took an interest, for example, in what I read, or actually, what I didn’t read.

:-O

Interesting but I think you need a different word for “those you give to”. In fact you probably need to split the circle into two – those you give to with some reciprocity expected (customers etc) and the true beneficiaries of the gift economy – those you give to without looking for something in return eg simply because you can. Indeed those you may never know! Myself for example. I don’t think describing me as a “customer” of yours really gets across our relationship…

David: I’m trying to get away entirely from terms like ‘customer’ or any of the other terms in the first column of my table. You/they are all ‘people I give to’ and (when you write back) also ‘people who give to me’. We need to get beyond expectations and reciprocity — if we give, we will receive (maybe from those we give to, maybe from others). But then, I’m an incorrigible idelaist ;-)

Dave, This information is very helpful to me, now that I am doing some online community managing. Do you have any new insights and updates for us since this posting in 2005?I love your book “Finding the Sweet Spot….” by the way. I wrote a quick overview of it on Sustainlane.com – perhaps you’d like to add a comment of your own to our readers there too?