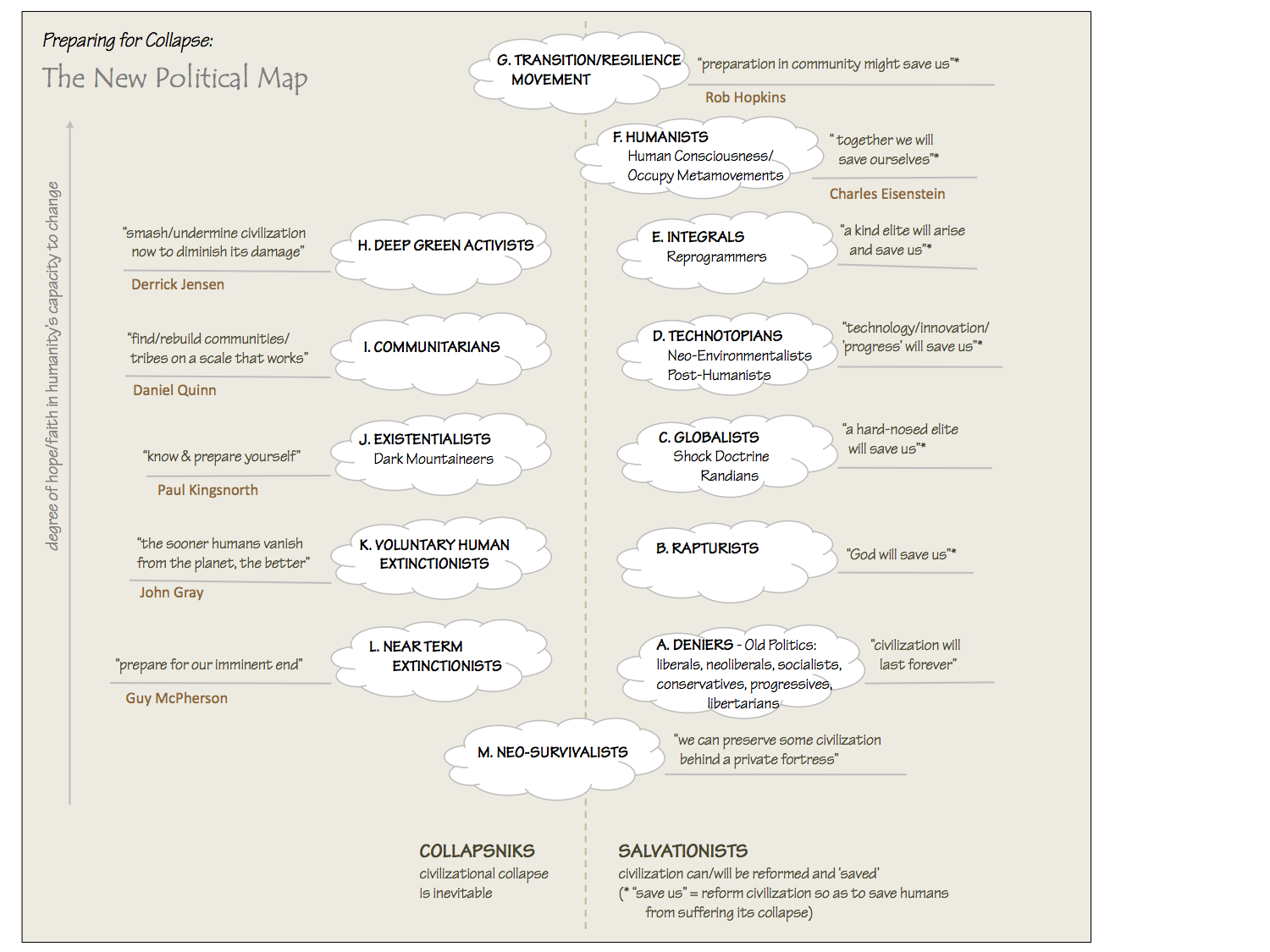

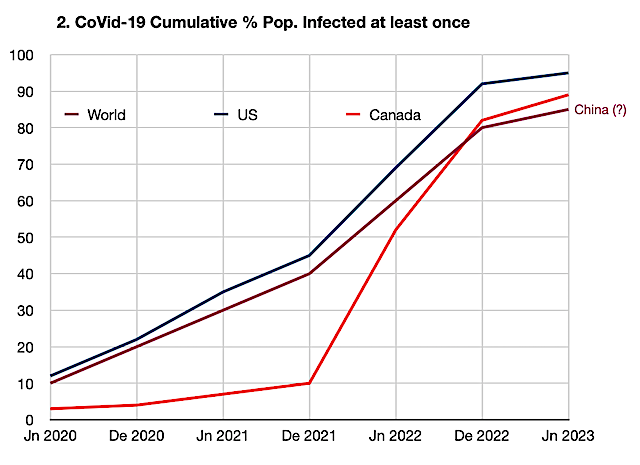

my now-slightly-outdated map of worldviews about collapse; right-click and open in a new tab to see it full-sized

It’s interesting to listen to social philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger try to reconcile his assessment of the state of the world with his vehement insistence that we have to try as hard we possibly can to avert the ‘metacrisis’ that threatens to bring about the collapse of human civilization and the extinction of most or all life on earth, including humans.

In a recent video, he said:

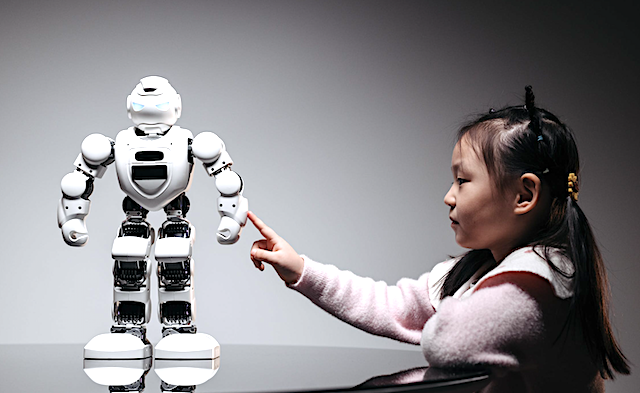

How can evolutionarily nasty chimpanzees with a high orientation for conflict and irrationality, with nuclear weapons and AI and synthetic biology, with a history of using technology in conflict-oriented and harm-externalizing ways, how can 8 billion of us with exponential tech [increasingly available to all] do a good job of governing that much power? It doesn’t actually look that promising.

Yet he insists that “we cannot know for certain” that we are fucked (or that we are not), so we each have a responsibility to do what we can, working with others, to pull us back from the brink.

His argument reveals a curious quirk about humans and our relationship to complexity, uncertainty, and hope. We seem completely preoccupied with what John Gray calls “the needs of the moment”, and it is clear that this preoccupation has directly produced the metacrisis (a combination of many, unintended, crises and system collapses — economic, ecological, political, social, health, educational, resource, technological, and, for some, spiritual/religious) in which we find ourselves. Yet we continue to cling to hope for our future when all logic says it’s unfounded.

Daniel harks back to when he was 12-15 years old, and first became aware of the monstrous cruelty to animals inherent in factory farming. (This is also how my own political activism started, though I was a bit older.) It seemed an impossibly complex problem to solve. But for Daniel, as long as there was some uncertainty about the outcome, some small possibility of an unknown occurrence (lab-produced animal-less meat?) that could unexpectedly intervene in the system and radically alter its trajectory, he could not allow that it was ever acceptable to give up, to shrug and say “There’s nothing we can do.”

Of course Daniel is enormously biologically, economically and culturally privileged, and it would be easy to say “Daniel, that’s easy for you to say…”. But while he acknowledges his enormous privilege, Daniel insists he is not exceptional or unusual, and that our inherent biophilia, instincts and basic human capacities make it possible, and essential, for everyone to play a role in understanding and working fiercely to resolve the metacrisis in the best way possible.

My philosophy of late has been that we have no free will, and that our beliefs and behaviours are entirely conditioned, such that “we’re all doing our best”. I think Daniel is saying “we can and will and must do better”.

I think he’s wrong about the capacities of the human species, though I do accept that if everyone in the world was as intelligent, as informed, as thoughtful, as open-minded, as engaged, as curious, as connected, as humble, as articulate, and as coherent in their thinking as he is, we really might be able to ‘save the world’ from what we have unintentionally wrought.

Instead, we are where we are. I don’t believe we can blame humans for being preoccupied with “the needs of the moment” and for only being able to do their inadequate-to-the-current-situation best.

Here’s a thought experiment to illustrate why I think this is so:

Suppose you knew, or believed, the following:

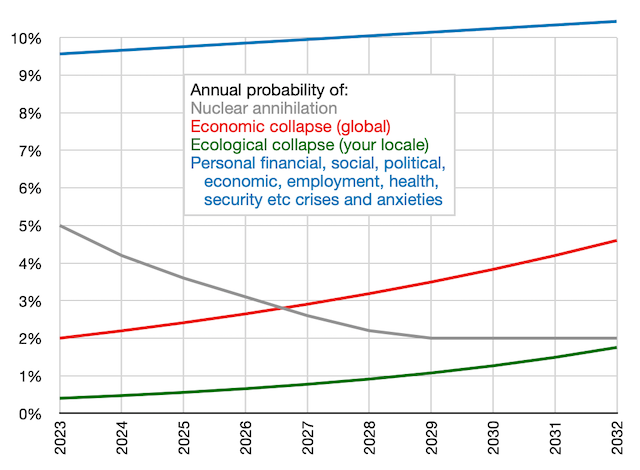

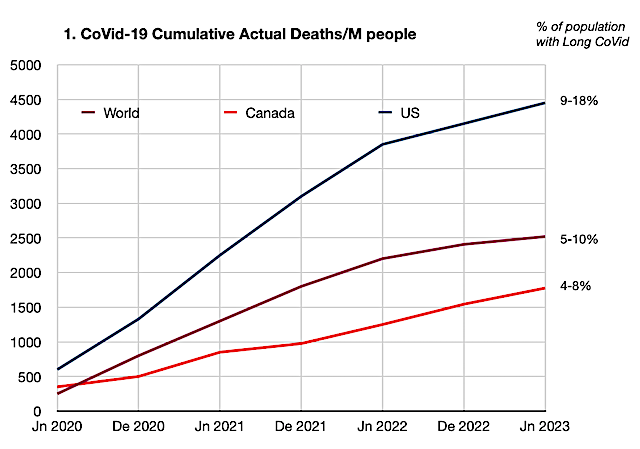

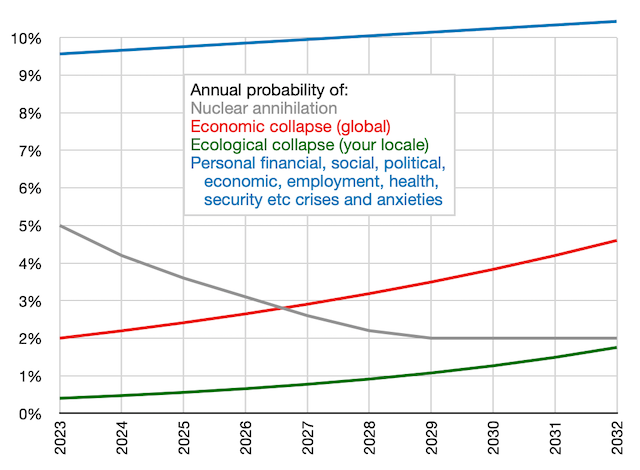

- The probability of a nuclear war this year is about 5%, easing slowly to about 2% in each year from 2026 onwards, should we outlive the Russia/US/NATO/China proxy wars in Ukraine and Taiwan.

- The probability of the economy collapsing permanently at some point over the next 15 years is 50%, rising to 95% over the following 15 years. [By “collapsing permanently” I mean a situation where the vast majority of the world’s population is hungry, permanently unemployed, and either squatting in place (unable to afford housing) or constantly transient or migrating.]

- The probability of an ecological catastrophe in your community occurring at some point in the next 15 years is 25%, rising to 95% over the following 15 years. [By “ecological catastrophe” I mean a situation where the vast majority of the community’s population is displaced and must migrate to another part of the world.]

I’m not asking you to accept these numbers as true — obviously we cannot know with any precision what is going to happen and when. But let’s assume you buy these probabilities. Your near-term perspective, now in 2023, of the existential risks you face would then be as illustrated below:

What demands the most of your attention, and perhaps keeps you awake at night, would naturally be the personal needs of the moment, shown in blue. If you have any bandwidth left for existential anxiety and are paying any attention to the doomscroll, your remaining preoccupation would likely be the risk of nuclear war, as its probability has soared over the past year. The horrific, longer-term economic and ecological (and other) crises we face would understandably be pushed to the back of your mind.

There’s nothing wrong-headed or inappropriately selfish about that. We have survived because our conditioning has inclined us to focus on the personal and the short-term.

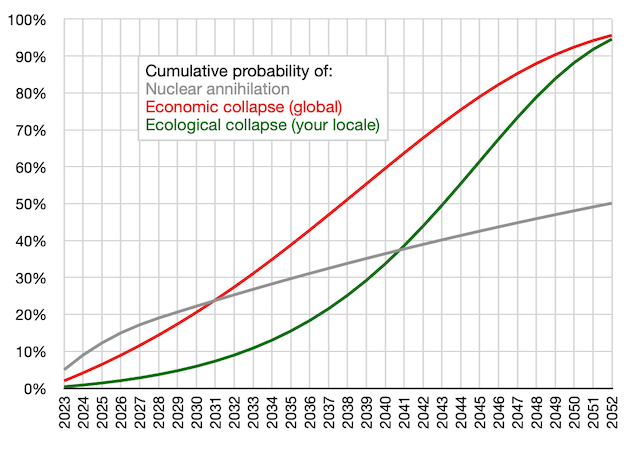

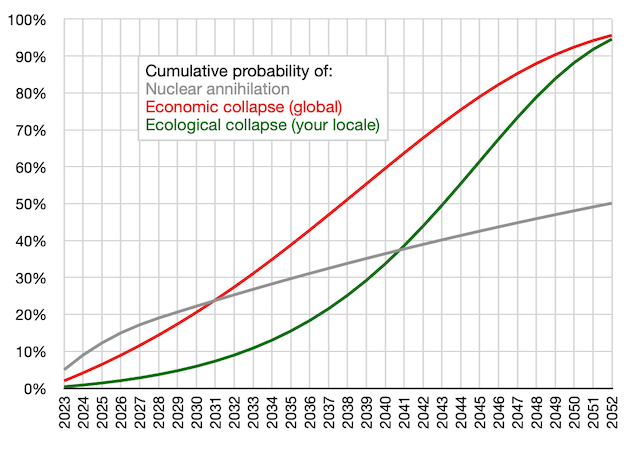

But what if we extended the chart above over a longer-term risk horizon, and looked at the cumulative risks of these elements of the metacrisis, rather than the annual risks? Of course, the further out we go, the greater the uncertainty and the likelihood of our guess being wrong. But this is what it might look like, using the same hypothetical assumptions above:

“It doesn’t look promising!”

This chart suggests a different focus for how we view and prioritize the crises we are facing. This way of looking at them makes a lot of sense, logically and statistically, but this is not how humans make sense of things. For a start, the longer out we go, the more we are inclined to discount our belief in the likelihood of these crises happening, because of their enormous uncertainty*. Secondly, we know that such predictions are prone to being rendered unreliable and useless by “black swan” events (like pandemics), by novel technologies, and by other unforeseeable developments (like cosmic radiation, asteroids, and solar flares). And third, we don’t think in terms of cumulative risk; like lousy casino players, we only see one roll ahead, and if we dodge a bullet, we think the likelihood of dodging the next one is suddenly much higher.

So if we make it to 2032 (a toss-up), or 2039 (unlikely) with none of these crises having occurred, we are probably going to be unduly optimistic that they won’t happen in the next decade or two either (just as the Davos gnomes were ridiculously optimistic in late 2019 that there would be no pandemic, because there hadn’t been one recently). Same logic for the “big one” destroying Cascadia.

And when/if our systems are still basically functional in the 2030s, it’s likely our focus will still be the short-term challenges we face over the next year or two, which means we will remain preoccupied with our personal needs of the moment, until global economic or local ecological collapse changes everything.

That is one reason we will not address the metacrisis until it is too late. There is another, very human reason, and that is that we can’t, and don’t want to try to, fathom the enormous complexity and interrelatedness of the elements of the metacrisis, each one of which is enormously complex in itself. For most, it’s enough to make our heads explode. We believe it to be impossible to understand and deal with, so it in fact becomes impossible to understand and deal with. This is what “doing our best” means for human animals. And that is not a criticism.

Yet despite this, we hope. As my map of the different types of Salvationists at the top of this post describes, hope comes in lots of flavours: Hope that the gods or aliens will take care of us. Hope that technology and innovation will come to the rescue. Hope that some human elite of leaders, beneficent or hard-nosed, will save us from ourselves. Hope that a massive spontaneous return to self-sufficient community-based living or global uplifting of human consciousness will solve the crisis. Place your bets and spin the wheel.

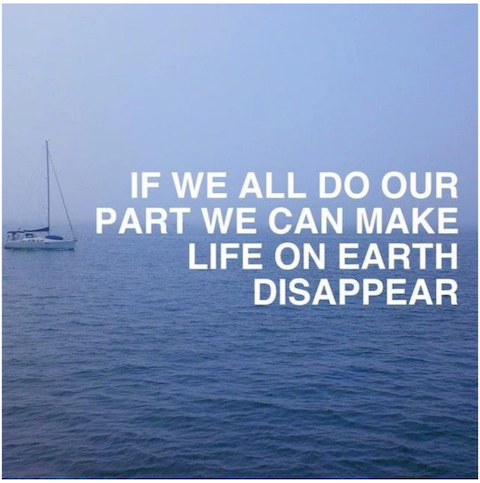

And then there are deniers who hope and believe that it’s all a hoax. And there are the NTHE Gaia-lovers who hope our awful species will perish quickly so the planet can start to recover from the human experiment sooner rather than later.

What is behind this hope? What is it about our perverse species that uniquely chooses to believe things, and do things, based purely on this thing called hope? Is it some kind of mental illness endemic to humans?

What causes us to elect a president who runs a campaign based solely on hope — twice? What causes abused spouses and children to stay around in the hope the abuser is going to change? What causes people to desperately keep loved-ones on life support, when the prognosis is dismal? Why does Hollywood, playing to the crowd, show success at CPR at a rate ten times higher than its real-life success rate? Why do so many believe that the only alternative to unwarranted hope is crippling despair?

I have said, ad nauseam, that we believe what we want to believe, and the truth be damned. So it must follow that hope is what we want to believe is true, and want to believe will happen, even when we think that belief is fraught with risk. Hope is future-oriented, and there is evidence that we are the only species on the planet that is so oriented. What is underlying that hopeful belief? Is it shame or guilt about what we have done wrong or failed to do successfully (like leave a healthy planet for our children) up ’til now? Is it anger about past ‘wrongs’ we want and hope to see atoned? Is it fear of a future we can’t bear to face, so we mask it with hopefulness?

I have, for now, come to grips with a realization that we seem to have no free will or control over our actions and inactions. When I acknowledged that everything we do is conditioned, I was able to give up hope. We can’t know or control what the future will bring, so what will happen is the only thing that could have happened. If we are hopeful on that basis, we are almost sure to be disappointed. But when we are disappointed, we may just double-down and hope even more fervently that things will be better next time, or next year. We are hope junkies.

Caitlin Johnstone just wrote a very eloquent, lovely. heartfelt essay about hope and wonder. On hope, in remarkably Schmachtenberger-ish language, she writes:

Hopelessness, when it comes to the fate of humanity, is an irrational position. The belief that we’re all inevitably going to destroy ourselves or keep marching into the depths of dystopia to the beat of the propaganda drum assumes a level of knowledge that nobody can possibly have. Nobody could possibly have enough information to draw that conclusion with any degree of confidence, and believing that you have is actually a bit arrogant. You don’t know what the future holds for our species, what unpredictable sociological, technological, environmental or situational surprises lie in wait that could cause a radical deviation from the norm… Hopelessness is the baseless and irrational shrinking of possibilities down to the spectrum of what’s known.

Yes, we cannot know, but lots of research shows that the people who have studied and learned the most about history and human nature and the current state of the world and how it works, are the most pessimistic about the future — the least hopeful. I’ve talked to enough climate scientists to think this is probably true.

And yes, we cannot know enough to be sure of the endgame, or even if there will be one. But, on the balance of probabilities, we can get a pretty strong sense that “it doesn’t look promising”. Why, then, can’t we seem to manage to move beyond hope, and just accept what is, and how fascinating the human experiment has been, despite its discouraging trajectory?

In her essay Caitlin moves on, deliciously, from hope to wonder:

If you really open your eyes, you’ll notice that the world is crackling with so much radiant beauty and wonder that even if we were to lose it all tomorrow, it would have been enough. A lucid perception of reality brings with it an experience of awe, and an on-your-knees gratitude for the fact that there was ever anything at all. From a perspective that isn’t clouded with mental narrative and internal distraction, each moment is too miraculous and too priceless a gift to get hung up on the possibility that it might not last.

Wonder is always accessible, even in the depths of sadness or depression. You might not always be able to find it in the trees or the butterflies, but you can always find it somewhere, often in the sadness itself. Even in the pain and despondency. Even in the car exhaust and the tattered billboards. Even in the background shimmering of existence. It’s always there to be found; you just might have to zoom out or zoom in your camera in order to find your access point to it.

Yes, and yes, there is wonder! The joyful pessimist in me finds it everywhere. The eight billion of us comprise only 7% of the over 100 billion humans who have ever lived on this planet. We are among the blessed 7% who will possibly get to witness the final chapter of the human experiment, who get to know how the story ends! And if it ends badly, well, that’s the only way it could have ended. All civilizations, and all stories, end. We all did our best. Nothing to be sad or ashamed about.

It doesn’t have to have a happy ending to be a wonderful story.

So, on the balance of probabilities, it’s more-or-less hopeless. And that’s fine, because we don’t need to be hopeful. Other creatures have lived for millions or billions of years without the need for hope. They understand this, in a way our species, smart and destructive and reckless and whiny as a young child in a family of patient, wise elders, is still far from learning.

If they have a purpose, it has nothing to do with hope, and everything to do with wonder. We might learn this, if we last long enough.

But I’m not hopeful.

* At the other extreme, there is an emotionally unmoored but very well-financed fringe group, including Elon Musk, who subscribe to a belief called Longtermism, that advocates actions, even if they could entail massive death and suffering of the planet’s current inhabitants, if those actions increased the odds of even more humans being alive in the far distant future. (Uncertainty is not factored in to their ghastly calculus.)