This is another post in my ongoing personal exploration of ‘who we (human beings) are’, how we got that way, and how, at the individual level, we might learn to better heal, better adapt, and better prepare ourselves for what’s to come.

I‘m a pretty fearful guy. I spend a lot of time trying to work up the courage and/or energy to do important things, and not much actually voluntarily doing anything important (I’m comfortably retired from paid work, so I am fortunate to not have to do anything).

At the risk of appearing to rationalize my unproductivity, I have a theory for why I am this way: Our culture wants us fearful and (emotionally) flattened. Here’s my thinking:

Back when there were only a few million of our species, we had no real need for culture. When I observe wild creatures, I see them living “in the now”. They will do what is needed to help the flock/herd/group in the moment, and most wild creatures are a lot more generous and altruistic than we might think. What they are not is anxious or fearful about the future, or in thrall to their collective culture. That’s in part because they ‘know’ they have no control over the future, so there is no evolutionary point in them imagining it or worrying about it. Their fears are immediate, and require a quick fight/flight response, after which the anger and/or sorrow they felt when the fear was realized, is discharged, and they return to living joyfully in Now Time. That’s not to say they don’t feel grief at the loss or suffering of a loved one — just that they are not fruitlessly consumed or debilitated by these feelings.

Wild creatures have cultures (read Bernd Heinrich’s works on corvids if you want to learn more about avian cultures), but these cultures are simple emergent properties of the reality of their lives; culture is not necessary to their evolutionary success and does not impose itself on individuals in the group. Wild creatures do what they do because their instinctive, intellectual, sensory and emotional ‘knowledge’ guides them. They may scrap with others in their group, and may not always get what they want, and they are able in the moment to collaborate brilliantly to achieve a shared goal, but ultimately they make their own culturally-unencumbered decisions.

When human populations started to outstrip the carrying capacity of our ecosystems (the reason why we did so is a subject for another essay) it became necessary for our species to ‘settle’, and to create new political, economic and social systems just to survive in unnaturally large numbers and concentrations. Democracy and personal freedoms don’t scale well, especially in situations of horrific and unnatural overcrowding, so as these human systems grew larger they had to become ever-more coercive — we had to be forced to conform, to obey others and cultural “rules”, to “settle” for less than what our wild selves had always been accustomed to, and will always yearn for.

As our human numbers accelerated and soared past a billion, the levels of human violence and oppression have ratcheted up commensurately. So have the numbers physically imprisoned — in jails, ghettos, camps, and (in Gaza for example) even whole nations.

But physical violence and physical constraints have not been enough to keep us in line. To submit more and more of the ever-increasing plague of human numbers to the necessary levels of restraint and suppression of our natural behaviours, psychological violence has been required as well. What I see, all over the world, are two now-endemic forms of psychological violence invoked to keep seven billion people in our culture’s thrall:

- the social construction and constant triggering of a new set of crippling fears via learned helplessness, and

- the emotional flattening of the human spirit through social prohibitions and inurement.

To inure is “to habituate to something undesirable, especially by prolonged subjection” or acculturation. If you are subjected to something long enough and often enough (e.g. spending time in slaughterhouses or jails or emergency wards or factory farms or “old age” homes or street gangs or torture prisons or refugee camps or ghettos or the armed forces or police forces, or living with an abuser, or watching violent “entertainment”) you become habituated to it. You become unable to feel the strong negative emotions and visceral revulsion that you would if this were a rare or brief event. You cannot. You emotionally detach, disengage, dissociate. No one can sustain that intensity of emotion indefinitely. The emotion gets suppressed, turned inward, and eventually the chemical reaction that occurs no longer has the same effect. You become emotionally flattened, numbed.

From the perspective of a massive human culture that is trying to get all seven billion of its members to work hard without anger, grief, outrage, or complaint, such emotional flattening provides a huge evolutionary advantage. If you can be inured to not care, or to not care to know, you can be made to do anything. Or, in the face of continued cultural atrocities, to do nothing.

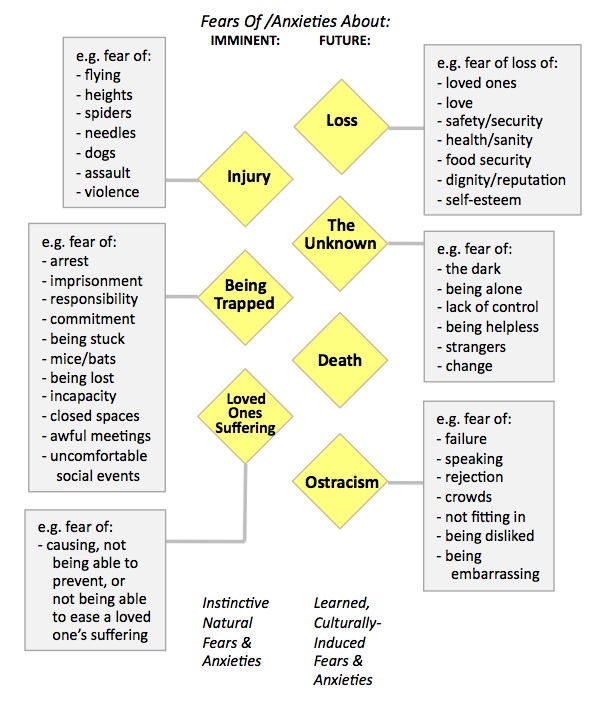

But there is an even more powerful tool that can be brought to bear to wield control over billions of people — fear. Fear is a natural phenomenon — most creatures have evolved instinctive fears of injury, and of being trapped, and of imminent harm happening to their loved ones, and these instincts have helped them survive.

Humans, however, thanks to our exceptional imaginations and memory and our invention of “Clock” Time, are capable of whole sets of additional fears about things that are either outside our control or are about the future. It doesn’t matter whether we are able to do anything useful with these fears. If they are invoked, we will fear nonetheless — and groups that are able to invoke widespread fear among others can capitalize brilliantly on it. Here are some of the things we humans fear (the taxonomy is mine, and is not intended to be complete or scientific); the ones on the right are those fears our culture has added to our instinctive repertoire, and thence exploited mercilessly and relentlessly to keep us in line:

Fearful and flattened. That’s what our industrial growth culture wants and needs of its members, now that it is a global monoculture strained to its absolute limits. Unless exercised in a culturally-approved way (such as “competitive” sports, wars, or abuse of one’s work or social “subordinates”), or locked away behind closed doors where there is plausible deniability, anger is now met with quick and violent suppression. Peaceful but angry demonstrations are met with heavily-armed stormtroopers. Anyone who even discusses angry resistance to the ecological desolation of our planet, to the theft and pillaging of Earth’s resources for the benefit of a tiny rapacious 1%, or to wars over oil or ideology, is branded a “terrorist” and subject to “disappearance”, extraordinary rendition to torture prisons, and/or indefinite imprisonment.

Likewise, feelings of debilitating grief, which I think are perfectly normal in our terrible world, have been pathologized and are now treated with large doses of anti-depressants or, failing that, ostracism and/or incarceration or other institutionalization. Our industrial culture teaches us to self-victimize. We are to blame, we are told, for our own unemployment and poverty (due to personal laziness or lack of moral fibre). We are to blame, too, for our own chronic illnesses (due to our poor eating and exercising habits). Suicide is, of course, treated not only as a sign of irresponsibility, but as a crime.

Our culture employs propaganda not only to divert responsibility for our anger and grief to ourselves, but also to keep us fearful. The propaganda machine creates a worldview of danger and scarcity, consuming us with fear of attack, of failure, of loss (especially loss of love), of uncertainty, of not fitting in and “not having enough”. And, of course, of death.

Because of our brain’s vulnerability to these future, unpredictable, easily-exaggerated and unactionable fears, our culture can exploit us by playing on our anxieties — re-triggerable dreads that precede fear and subside when those fears are not realized. Anxieties are conceivable fears. Any fear that can be conceived — terrorists, foreigners, rejection, threats of all kinds — can be blown up and exploited and used to control us and our behaviour, and even to immobilize us.

This cultural immobilization runs deeper than most of us ever realize. People on their death-beds, asked what they most regret in their lives, overwhelmingly cite things they regret not doing rather than things they did, and most of those ‘inactions’ are the result of cultural constraints or personal self-constraints, self-censorship of action, rather than the result of never having the opportunity to do those things. Daniel Gilbert‘s research shows that (thanks to our cultural programming) we have a tendency to overestimate the impact of current and future events and decisions on our future happiness, and this makes us timid and risk-averse in making those decisions, and overly preoccupied with the future instead of our current happiness. And many people’s reaction to Derrick Jensen’s relentless urging of us to act on our instincts in defence of our suffering and dying planet, is resentment at being pushed to do what is culturally-prohibited, rather than anger at the culture that is, with our own complicity, holding us back.

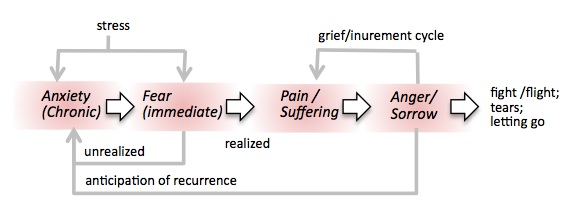

There are two cycles, which I think are unique to our species (or at least to large-brained species), that can be provoked with appropriate propaganda, as shown in the diagram below.

Because our brains create stories (mental representations of what is, was, may be or will be, and of who we are and why we are that way), we can and do constantly ‘re-enact’ situations which caused us pain and suffering — what I call the grief/inurement cycle. We feel the pain, we create a story to explain it, that story is so vivid and memorable that recalling it re-invokes the pain, and so on. We can become incapacitated by such suffering, until enough cycles have passed that we begin to forget these stories and heal. This aids a coercive culture in two ways: through the initial debilitation that prevents us from acting against the perpetrator of the outrage that produced the pain, and through the inurement that comes when we become so desensitized to the outrages, and the pain and suffering, that we begin to accept them as normal, the only way to live.

And then there’s the feedback cycle from anger and sorrow to chronic anxiety, as our brains imagine situations in which the atrocity that caused our pain could recur again and again, to the point this anxiety begins to immobilize us, and makes us pliable to cultural forces that promise to relieve us of or protect us from the things we have learned to fear. As Robert Sapolsky‘s research has shown, this anxiety/fear/pain/anger/grief feedback cycle is an emergent property and unintended consequence of our brain’s exceptional ability to imagine and recall, and the anxiety, especially in situations where events are outside our control, is unhealthy and useless — except to the culture that wants to use it to control us. This cycle also produces “learned helplessness” — the invalid but propaganda-reinforced sense that there is nothing we can do, except hope and trust that our ‘leaders’ can ‘save’ us.

Those who presume to be able to tell us how to deal with and ‘overcome’ our fears suggest six broad approaches to doing so. None of them is simple, or else we would all be using it. But the harder approaches (at least, harder for me: your experience may be different) seem to me to offer more effective ways of interrupting the vicious cycle of suffering, grief and inurement, or the vicious cycle of chronic anxiety and learned helplessness. Here’s a table that shows these six broad approaches to dealing with fear, and my personal assessment of their potential efficacy (again, your experience may be different):

| Approach | Efficacy | Risk | How Easy/Difficult? |

| 1. Avoid occurrence | Low | Incapacitation | Moderately difficult |

| 2. Discharge | Low | Addiction | Relatively easy |

| 3. Conditioning | Maybe | Desensitization | Difficult |

| 4. Learn & prepare | Maybe | Self-deception | Moderately difficult |

| 5. Accept & let go | High | Detachment | Very difficult |

| 6. Live in the Now | High | Anomie | Very difficult |

The first, and obvious, approach is to try to avoid situations that give rise to fear or anxiety in the first place, but I’m learning that this is futile. The more you try to protect yourself, the more vulnerable you become to events and situations you could not avoid, and in the process you can incapacitate yourself to the point you become afraid to do anything.

Another common approach is to try to discharge, through physical means or through conversation therapies or other behavioural techniques, the emotion that the fear gives rise to. Many people believe wild animals do this when they “shake off” their emotion after averting danger. The theory is that this “discharging” cuts off both the grief/inurement cycle and the anxiety/fear/pain/anger/sorrow cycle by preventing the pain from being constantly revisited and reimagined and dwelled upon. But I would argue that we are incapable of having that much control over our memories and imaginations, and that while discharging might provide temporary relief, in the long term it is more likely to lead to addiction to the act of discharging (especially dangerous if that discharging is expressed as violence or unrestrained anger against others), than to any relief from either pain or recurring anxiety.

A newer method of dealing with fears is conditioning. For those with fear of flying, for example, the idea is to have the fearful person experience many safe flying experiences gradually, so that the mental connection between the experience and the feeling of pain is broken, and eventually the anticipation of the experience arouses no anxiety. I know some people for whom this has worked (and others for whom it has not). The danger is that you can end up being desensitized to real risks based on limited experiences. What happens if you are conditioning yourself to overcome fear of flying and your plane has an emergency landing? Trauma, I would think.

A fourth approach is learning and preparation. The more you know about what you can actually do if a fearful situation arises, in theory the less anxious you are likely to be about its potential occurrence. You are, in effect, combating the learned helplessness by giving yourself something (knowledge and experience) that gives you more control over a potential future experience. The danger here is that you may think you have more control than you really have, and that self-deception may lead to underreaction or complacency when the risk is real.

Now we come to the two methods I’ve been working on most recently. I think they’re connected. The idea of “letting go” of our stories about what might happen (our anxieties) to the extent they are beyond our control is extremely difficult, and I appreciate the skepticism of those who assert we can think ourselves out of our pain and anger and sorrow and fear. But our anxieties and fears and stories about things we cannot really know and cannot control is a ‘learned’ behaviour, so it should be something that, with practice and self-awareness and self-knowledge and self-management, can be unlearned.

And the sixth approach, of simply Living in the Now, and rejecting the stories our minds (and our culture) tell us about ourselves and others, and about what is and was and will be (or may be) in the future, before they even become part of our belief system and worldview, seems to me likewise a means of living more naturally, of being more present. I have had moments when I feel fully present, when I am simultaneously very aware (and self-aware) and very relaxed (and hence more competent and resilient in the moment), and in such moments I feel legitimately fearless. I want that feeling to last forever, and sense that this is the way most wild creatures, unencumbered by diabolically imaginative and past- and future-oriented brains, live their whole lives (except when danger is imminent), joyfully, naturally, and arguably more sensibly than we.

So my sense is that this practising of presence, this learning to live in Now Time and to let go what I cannot predict or control, is what I must pursue with increasing energy and commitment. I see it as being part of rediscovering who I really am, this feral, nobody-but-myself, me. And I think this is essential to cultural liberation and hence to the emotional flatness and fearfulness that is so much a part of the “everybody-else” me I have been acting as for so many years.

Maybe this is what we must all learn to do if we want to be able to do the essential work of preparing ourselves, our loved ones and our communities for the terrible crises ahead, when our industrial-growth civilization culture collapses and loosens its well-intentioned hold on the rest of us. Maybe that preparation is nothing more than this learning, this becoming ready to live without dependence on and coercion by culture. So that when it happens, we will know, as liberated, wild creatures, exactly what to do, in the moment.

Our perhaps it’s just me. Perhaps what I am seeing as the dark constraint of and the emotional imprisonment by our culture, is just my own projection, my own neat and convenient story for my own inaction, now. I don’t know. I’ll let you know if I figure it out.

How, possibly, could it be ‘just you’?

Thanks for this important piece, Dave.

Hi Dave,

Good Stuff. My only complaint is that I think you villainize culture too much. There are inumerable examples of healthy, vibrant, sustainable cultures — both human and non-human. It is nothing more than a shared view of the world and our place in it. The nature of our place (our immediate, physical environment), the gods of that place (or, if you prefer — the non-human inhabitants of “our” place), the way we cook our food, the food we prefer to eat. The clothes and homes we live in. The stories we tell and the music we create. Just because this one culture has become so horrific, don’t demonize the rest as well….

On Fear. I think you are very much correct in describing the role of fear in our culture. In another way, its something I have thought long about and spoken of frequently. It is a coercive force and I have long argued that any coercive force only has power if one allows it to have power. Sure, someone can hold a knife to my throat and demand my wallet — but only *I* can decide whether to acquiesce to that coercion. In most cases I will, because the threat has greater value than the wallet in my pocket. But I hate when people say “I had no choice” about *anything* — because there is ALWAYS a choice. This helplessness is absolutely a cultural story that civilization itself has been passing along all these millenia. Look at the OWS…. dramatic, violent, aggressive action has only caused the people actively involved to become *more* determined. The value of what they seek outweighs the potential losses they face. So long as that is the case, the movement will continue, and continue to draw more support. On the flip… if the powers that be give just an inch, it might be that the movement would begin to fail. We will see here in the near future, I suspect…..

One more thing… making a choice is always an action. Allowing coercion to succeed is a lack of action. Usually. Another reason it tends to succeed….

Janene

Dave- Once again I appreciate and admire your willingness to put yourself out there on an issue of great importance. I invite you to consider the proposition that it is also possible to accept and let go, live in the now and *still take action* as you deem appropriate. This is (at least in some cases)the Buddhist way and I suspect there are other traditions in religion, psychology or politics where this is possible.

For your own sake, I hope that you will be blissfully living “in the moment” one day when the drones are hanging outside your window monitoring your every move. Or when you are stuck in a detention camp for simply having an opinion that doesn’t agree with the state. Hoping for collapse is not a foolproof plan. When you get a chance, research some of the key players in the transition town/sustainability/new economy movement – their origins (going back to the 70’s). Discover who funds organizations (like David Korten’s)? What does Herman Daly have to do with the Club of Rome? What do the Rockefellers have to do with the sustainability movement? Who funds 350.org? Where was Lester Brown back in the early 70’s? What agenda did he support? Who is Neva Goodwin of the New Economics Institute? What does she stand to gain from being involved? Dig a little deeper.

Enjoy your new homework. :-)

Beth/Janene/DJ/Droid: Thanks for your comments. Janene, my beef is with industrial growth ‘civilization’ culture, not culture in general. And even this terrible culture is well-intentioned and worked very well, and sustainably, for quite a while.

Droid: I’m not hoping for collapse. I think it’s going to be ghastly, awful beyond the imagining of most of us. But as the Soviets learned, you can’t monitor, coerce and jail everyone, unless there is a viable infrastructure and source of revenues to fund the prisons, pay the army, run the propaganda machines etc. I’m less worried about Big Brother than about running out of water. The more I learn about the ‘powers that be’ the more I realize No One is In Control. As for the ‘leaders’ of the ‘environmental movement’, I know that a lot of them are apologists and even shills for corporatists. A lot more are genuine but very naive about what can really be done to bring about change. I was around in the 70s when the environmental movement was in its heyday. The real enemy, as Pogo said, is us — we are all caught in an unsustainable political/economic system that is now running out of anyone’s control, and it’s too big, even if collective agreement and energy could be brought to bear, to rein it in before it collapses of its own weight.

In other words, you are not interested in doing your homework, which is too bad because your ideas about the future collapse are based on the propaganda of the key players. It’s easy to dismiss what you don’t bother to know. But I’ll leave you be at this point…no sense in pressing. Maybe you’ll decide to look into it later.

Dave,

always so much to be gained from your honesty to explore the conections between your inner world and the Earth outside (and inside us…biophillia…). However, perhaps cause and effect in relation to fear is more “grey” than you suggest. Evolution may have hardwired us to find some/many of the culturally induced fears on the right of your table actually innate. These fears could be genetically inbuilt increasing our ability to survive in groups through various feedbacks and thus contribute to our swelling numbers. We do think about our future, hence our big brains. Our culture may want us fearful and emotionally flattened but our fear is also interwoven with our brains sense of the future (that helped cause the taker tribe to spread like a virus).

Our brains have evolved to survive, not to be truth seeking devices that can neatly separate fear into two columns- are the inside and the outside just the same thing?. My young dog can be concerned for the future fears as I have seen him worried/fearful of certian things..particulary the unknown. Is this perhapes because he is young and has to have some inbuilt fear about the future, as if he was just always in the moment this approach would be self limiting, thus contridicting natural selection. Grey area.

You open by risking rationalising your unproductivity (and fear)with a theory about the culture outside you. Yet I think it is more (from your recent posts)that you know that “action is consolatory, it is the enemy of thought and the friend of flattering illusions”. This would be confirmed with your insightful eassay the second denial. And yet you share with most that view your blog the feeling your actions come from a sense of responsibility. Maybe we fear fear due to our culture and yet it also means we are actually here…able to communicate.

Love it how you mention awful meetings as a fear. I work in education and know that one! Is one of your fears not being able to communicate??

Well, not to be trite, but so be it; “We have nothing to fear but fear itself…” and, ‘one promotes that which one dwells upon’.

So, it would seem that numbers five (Accept and let go) and six (Live in the Now) are the way to go. But I agree with djclausewitz’ comment that it is possible (and, to my mind, necessary) to ‘still take action’ while doing/being so.

As I get older .. I find that there’s little I am scared / fearful of (other than pain that can’t be controlled), and virtually nothing can get me into an anxious state.

I guess I am realizing I’ve got anywhere from 1 day to maybe 25 – 30 years left, and I can’t seem to find the point to being scared, anxious or unhappy. Somehow, that feels quite a bit like living in the present ?

I might have gotten to this stage by spending a lot of time with my father during the last two years of his life, and watching / being with him during his transition.

After re-reading your post, I feel I understand fear a little better and would question my mild critisim of your grey areas as you cover the intincts and complexities etc with thought and the closing comment you state you are still figuring it out. Our culture is saturated with fear…and it is manipulated by some… but I still doubt we can control or escape it for any lenght of time in our daily travels. At least we can see it at a conscious level. Please keep communicating…cheers.

I think your strategy makes sense, I like the idea of “rejecting the stories our minds (and our culture) tell us about ourselves and others, and about what is and was and will be (or may be) in the future”, but I sure find that difficult! My mind loves to invent anxious stories, and most of the articles that I read about the future of the world are asking the readers to share more or less believable stories (about collapse, control by the powers that be, mass uprising, technological progress, etc.). How am I going to cast all these stories aside? Can I learn to just see things as they are, without letting the stories (concepts) distort my view, “rediscovering who I really am, this feral, nobody-but-myself, me”? That project seems tough. I’m trying meditation, but finding that difficult too.

We are on the same page. it’s strange, because realizing this seems change everything that goes on in your head.

Yeah Dave! Thanks for sharing what is in your heart. I am constantly feeling chased by the feeling I am not “doing” anything. To flee from that I go into Second Life and chat. I tend to feel better but the deadlines pile up.(lol!) Let me share my thoughts on what is going on here. Instead of fear I like to talk of stress. There are five major ones as I see it – food – shelter – social inclusion – toxicity and physical trauma. There is a sweet spot somewhere in the middle and as we venture out in any direction (too little food, too much food) we get stressed and ultimately fearful. These are natural reactions that keep us safe. But drop a person in the 21st century and you see that the natural reactions to stress factors are out of play as we are several degrees away from a direct connection with what we need to have control over. For example, you want food security? Then you need a job. Or money. Where we evolved the answer was “manage your surroundings so they produce food”.

Now we are in a bind: you want food? Manage your money or do your job, knowing this is actually undermining your chances of getting food in the future as it is trashing the environment. And what is the natural reaction? Freeze, flight or fight. Want to feel secure in yourself? Then you need to fit into society. Again, to fit in you need to block your wish to start creating those changes that will bring security.

My solution? Well there has to be enough people around you you trust to be able to start making those changes and still feel part of group. The group needs to offer at least food security and community security. This is deep and powerful. Together we can do it. It’s just that our culture has had 10,000 years of developing away from the idea that we can. The culture we have as our heritage was one of being part of an empire. But we CAN form these tribes. We must. We must go from the way of the pyramid to the way of the circle. Let’s face it… corporations, money, jobs… they are sooooo last century!

Maslow lists the following characteristics of self-actualizers (1970, pp. 153-172):

14. resistance to enculturation; the transcendence of any particular culture

A contrast, occupies say “1% blah blah.” “Regular people,” say “what can I do,” and they go to work like the other 90% of the employed population. But they are both the same. Are they really doing something they love? Or are they caught up in some spin cycle of mass culture? Simply following. Unable to sense the conformance field, let alone ignore it and enjoy life.

http://www.abraham-maslow.com/m_motivation/Self-Actualization.asp