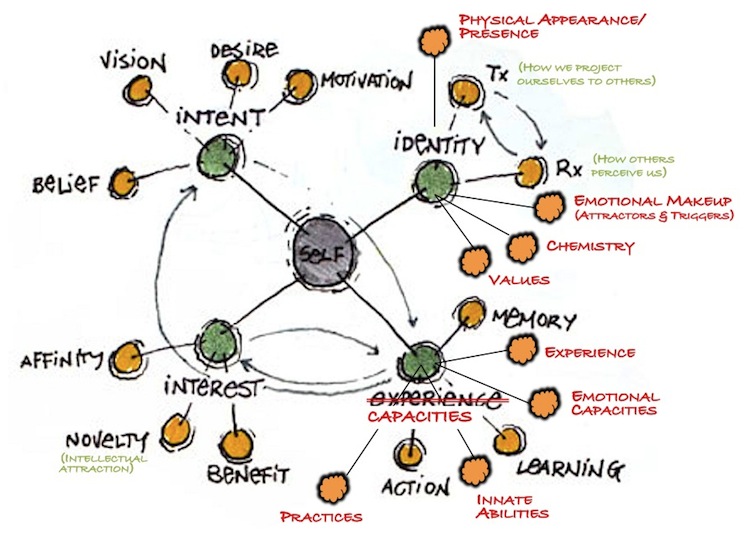

graphic of four types of community and the qualities that make each cohere, by Aaron Williamson (my suggested additions are in red)

Much is being written these days, in political, social, business and collapsnik circles, among others, about community. Most of it assumes that there is such a thing.

A few years ago I wrote a response to Aaron Williamson’s then-new model of community and identity, diagrammed above. Aaron acknowledged that “a community or potential community is a complex system” and that “community itself is an emergent quality — community, per se, does not exist; it is a perceived connection between a group of people based on overlaps of intent, identity, interest and experience”. These four aspects of our ‘selves’ are shown as green circles, above. Elements of each aspect are shown in orange circles.

In this model, overlaps between ‘selves’ can result in the emergence of different types of community:

- If the overlap is mainly common interests, it will emerge as a Community of Interest. Learning and recreational communities are often of this type.

- If the overlap is mainly common capacities, it will emerge as a Community of Practice. Co-workers, collaborators and alumni communities are often of this type.

- If the overlap is mainly common intent, it will emerge as an Intentional Community or Movement. Project teams, various communal living groups and activist groups are often of this type.

- If the overlap is mainly common identity, it will emerge as a Tribe. Partnerships, love/family relationships, gangs and cohabitants are often of this type.

At the time I wrote “You cannot create community, all you can do is try to create or influence conditions in such a way that the community self-creates (self-forms, self-organizes and self-manages) [and emerges] in a healthier, more sustainable and resilient way.” I identified what I thought were 8 key qualities of such healthy communities and their members: Effective processes for invitation, facilitation, and the building of members’ capacities, strong collective processes, and members’ individual skills of self-knowledge, self-awareness, self-caring, attention and appreciation.

It’s hard to find good enduring examples of such communities. The late, great Joe Bageant taught me that “community is born of necessity”. He showed me what that meant by telling me the story of the isolated village of Hopkins, Belize (while I was visiting him there). Hopkins was formed when a group of slave ships ran aground in a storm 300 years ago, and the survivors escaped and made their way up the Caribbean coast and created a new community there, one which thrived without intervention until it was wrecked just in the last generation by foreigners through trawler overfishing of the Gulf, and the imposition of land title laws (and fences, and walls) on their ‘free’ indigenous common land.

Why did this community succeed for so long? Because the escapees had no choice but to make it succeed; it was life-and-death. This is the ultimatum the collapse of our civilization’s systems and culture will soon present us all with, as possibly two billion climate refugees in a Great Migration bring about the ultimate clash of cultures and the final demise of all of our civilization’s systems.

This is why few of what we would like to call communities today, are actually that: It’s too easy for most to just pick up and leave when they don’t like the people, processes or circumstances of their adopted, emergent communities. There is no necessity holding us together when things get uncomfortable, no requirement to live with and love neighbours we don’t particularly like.

We seek community now for a number of non-essential reasons driven by individual wants and ambitions: attention and appreciation, collaboration on projects, movements and enterprises where we share goals, skills, needs or passions, as well as for protection from perceived threats. The people I met in Hopkins sometimes sought these things, but they weren’t what created or held together the community. And as that community is being destroyed from outside pressures (the loss of their primary food source and their land), what brought and kept them together won’t help them withstand its demise. To anyone who’s studied indigenous cultures, it’s an old story.

So we look for others with whom to form community, individually — online in social media and virtual worlds, in dating services, in ‘meetup’ groups, in clubs, in social organizations. But most of us drift in and out of such groups, dissatisfied with their offerings, mourning their inability to find what we really want — existential connection. All that expectation is loaded up on the shoulders of spouses, governments and employers to fill the existential gap, which they can’t hope to deliver.

The traditional places where people seeking community congregated — churches, higher learning institutions, guilds, cooperatives etc, are in disarray, their memberships falling. This is partly because we’ve become too picky about what we want from so-called community organizations. We want them to cater to our individual wants and needs, and their ‘commercial’ replacements assert that they offer that, though they do not.

So what is this ‘existential connection’ that is lacking in modern ‘communities’? At its heart, I think it is connection to place and to all other life on the planet, which most of us have become disconnected, even dissociated from. We all ‘know’ somehow that living naturally is communal, connected, mutual, integral, unselfish, and loving — the very opposite of individual and isolated and competitive and the ‘optimizing of self-interest’ that underlies our entire modern dysfunctional and massively destructive economic systems.

When I go to meetups of new groups now, I often find such a sense of absolute desperation for community (of all four types), that when they achieve even the brief illusion of that integral sense of community, many present will start to cry in unrestrained (and infectious) appreciation and joy. They will swear to have made vital lifelong connections. But a month later those apparent connections will have vanished. Desperation is not yet necessity. We return to our fragmented, community-less lives.

If you’ve been reading my stuff in the last few years, you’ll know I no longer proffer any ‘solutions’. This predicament is endemic to our modern, global, dog-eat-dog, utterly individualistic culture, a culture that has crushed all of the remaining sensible ones. The system has to fall before we will once again learn what it means to know the necessity of living in community, of being community. There is no cure, no ‘fix’ for Civilization Disease, the disease of disconnection, fear and antipathy.

The problem with systems, as I’ve explained before, is that they don’t really exist. So while in a way the ‘system’ is the problem (it’s associated with our incapacity to reconnect and hence rediscover true community), it’s actually just a label our pattern-seeking brains use to try to understand why things are the way they are. Yet our minds, our ‘selves’ that supposedly sit at the centre of our communities (as depicted in the chart above) are themselves just labels, concepts, pattern-making, attempts to make sense of what ‘we’ cannot hope to understand. (Aaron, as a non-dualist, hints at this, though perhaps wisely he doesn’t really get into it in his writings aimed at business clients who are likely addicted to these illusions, and fiercely ‘self’- and ‘system’-driven.

Some day, in a world probably millennia hence with many fewer human creatures, there will likely once again be real community everywhere on what’s left of our planet. But they will not be communities of interest, practice, experience, capacity or even identity. The ‘selves’ in the centre of Aaron’s model will not exist. There will be no need for these parochial communities, or the selves that cohere them. There will be community of necessity, delight and wonder, non-exclusionary, embracing all life, free from self. There will be no choice. In the meantime, there is nothing to be done. One day, everything will be free.

Good breakdown, Dave! I’m not sure illusion is the right word for community though. When I look at my monthly expenses I see what I pay to to my eco-village, and I see my emotional commitment as my email fills with discussions about it, it’s very real. Maybe the promise offered by community, of offering connection to earth, myself and each other to is illusory…

Recent work I’ve been doing on the commons finance canvas (http://canvas.avbp.net/?p=27) trying to make a comparison between company and community shows me that the promise of the firm, or company, is illusory too. In fact, of the two, a community with a commons is a much better bet as a way to satisfy needs.

Two things are striking: a community has an optimal size and does not need to grow. The very nature of a company drives growth. (A lot to discuss there.) The other thing is that the basic relational stance of a community is cooperation. In a company that tends to be collaboration but with an element of competition, it’s kind of socio-psychopathic from the beginning.

Another thing this line of enquiry is throwing up is the relationship with nature and natural resources (sic). The very design of a community encourages conservation and efficiency whereas the set-up of the firm more tends to drive linear, extractive practices (even more to discuss there). For those who read to the end of the article (http://canvas.avbp.net/?p=27) there is a comparison table that I’d love to discuss and develop.

Hi Dave,

Thanks for the very interesting read. I very much agree and just wanted to point out one example of a healthy and resilient community that functions amidst civilisation…Alcoholics Anonymous.

I live in central London and can only speak for AA here, but there are about 800 meetings a week here across the city. There are national/international conventions etc. It’s been going since 1935 and seems to be only gaining momentum.

Interestingly, it’s strength derives from the fact that for most members overcoming alcoholism is indeed a life or death scenario. And most cannot overcome addiction without some sort of strong community (it has been noted that the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but connection).

We share identity (‘alcoholics’), practice (the 12 steps, meetings, sponsorship, fellowship [AKA hanging out], etc.), interests (learning how to live non-dysfunctionally :P), experience/capacities (people who have been through the whole thing from start to finish have extremely valuable ‘expertise’ and experience in addiction/recovery, which is passed on).

There are also ‘traditions’ that function as rules to safeguard the resilience as well as effectiveness of the community (e.g. AA unity comes above personalities, groups are self-supporting through financial contributions of their members, policy of attraction not promotion, etc.).

Re: individualism, a lot of emphasis is placed on overcoming ego, doing service for the meetings (e.g. being secretary, treasurer, making tea – whatever it might be – the principle of being of service is more important than what you do) and generally helping others – particular those who are struggling.

I found your point about how easy it is to leave modern meetups if you encounter something you dislike particularly poignant… AA has many ‘quirks’ that many dislike – but that’s almost part of the programme of sobriety…facing difficulties and seeing them through rather than saying ‘fuck this’ and leaving the group. Here the fact that there is no real alternative to AA (in terms of community at least) and the extreme cost of relapse (i.e. having a shit life in addiction, possibly dying a horrible death) serve to maintain resilience.

It’s worth noting that the crushing impact of civilization on mental health does an excellent job of keeping the meeting rooms of AA nice and full, also.

We speak often of the “gift of desperation” as the thing that brought us into recovery…in this case, desperation became necessity => resilient community!

It is indeed a wonderful to be part of something larger than myself, that I absolutely cannot find anywhere else – no company, organisation, or even non-profit…there is a lack of existential glue in these… I feel no connection – everywhere else I experience the existential emptiness that you describe…

Just thought someone might be interested :)

Keep writing, Dave :)

Ben