This is #28 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk, hike, and explore in my local community.

mergansers in Bowen Island’s lagoon; my own photo

I‘m sitting on a bench in Lafarge Lake park, watching the ducks and listening to the conversations of the people passing by on the pathway that goes around the lake. It isn’t a real lake — it’s an abandoned quarry pit, named after a huge cement conglomerate, converted into a park by the city. But the ducks don’t seem to mind. Unlike most humans, they’re pretty resilient. Watching them brings to mind a passage from Dmitry Orlov’s book Communities That Abide, that tells the story of how birds self-organize in the face of collapse, adapting easily without needing a ‘leader’:

Fifty blackbirds nest in a dead tree, congregating and socializing raucously each evening, the babies squawking for food. Then someone cuts the tree down, and the birds scatter. Collapse. The tree-killer sells the wood and the empty nests for profit. The birds circle and regroup, and in a few hours find a new tree and start building new nests. Three days later, for the birds, it is exactly as it was before the fall. They understand community, and resilience.

Ducks get a really bad rap when it comes to the English and French languages. Their speech, described as a quack, is a term that has come to mean a charlatan, a professional fraud, based on the apparent nonsense they say. The French word for duck is canard, which in English means a fabricated story or hoax. And the French for quack is cancaner, a word that means both quacking and gossiping.

I find the quacking rather charming. To us it may be ‘nonsense’, but apparently ducks have at least 100 different ‘messages’ in their quacks that other ducks readily understand. They are supposedly almost as smart as corvids and psittacines (parrots), and that’s saying something.

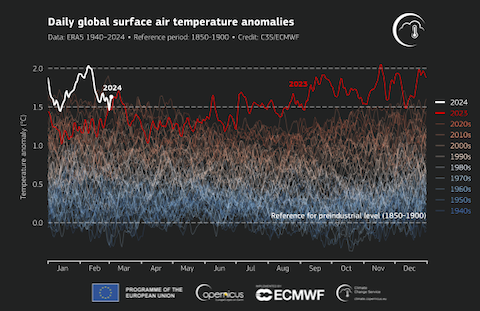

Today I am looking for the sights and sounds of joy, pleasure, and fun. This might seem an insensitive quest. After all, we are living in a world with grotesque genocides, wars of many different kinds, horrific cruelty to animals in factory farms and other institutions of torture, and the accelerating collapse of our entire civilization, including the ecological systems on which all life depends.

I think about this. On the way over to the lake, I saw dozens of old-fashioned, 1960s-style posters glued onto almost every lamppost — you know, the ones that were banned back then after it was found they were almost impossible to remove. All of these were protesting the current Nakba and genocide by Israel in Palestine.

I cheered the protesters when they gathered at city hall a few days earlier, but I really wondered whether it was accomplishing anything. In the 60s it was the atrocity of the Vietnam War that we were protesting, and I suppose, as with Vietnam, it’s sufficient, and necessary, to sow some doubt in people’s minds, especially when you can get a large turnout. But you’ll also entrench some people in their denial and opposition. For better and for worse, we do condition each other. We do what we can, what we must.

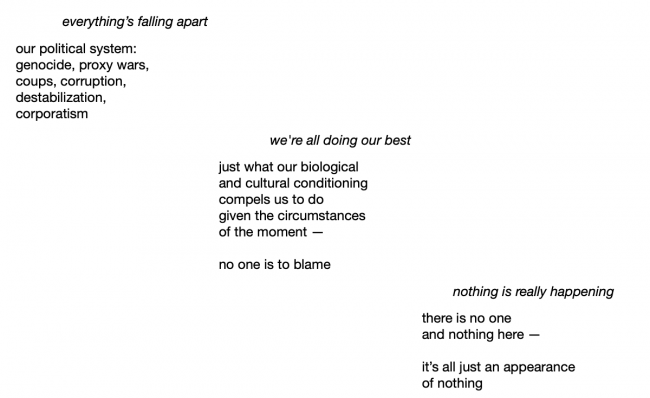

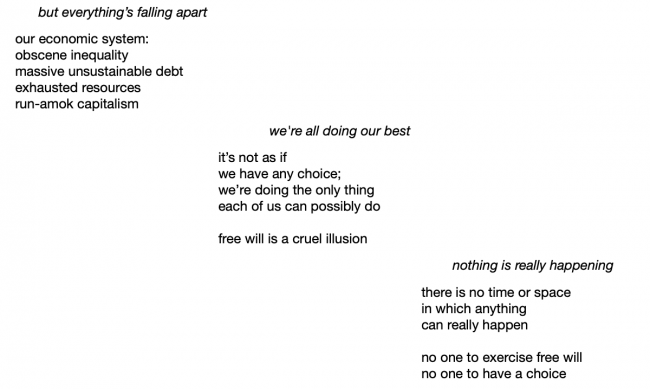

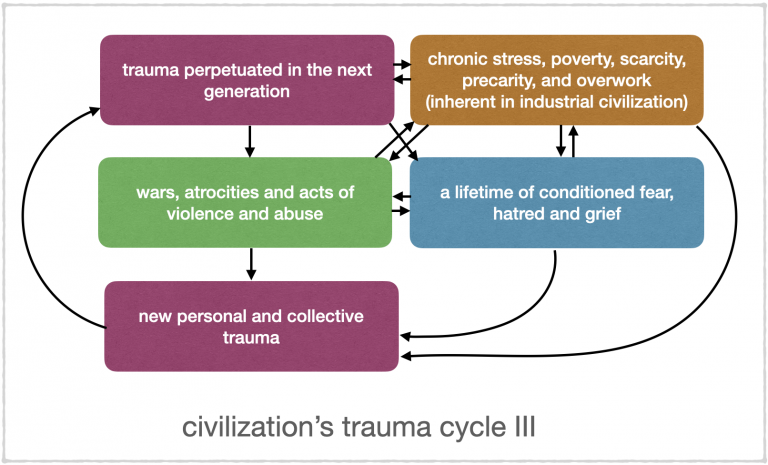

I think about the fact that it would seem all our behaviour is conditioned, and we cannot help what we do, including the commission of atrocities and acts of war and traumatizing violence. I sigh. I know I write about this all the time, but I suspect that the people who read my blog largely already share my worldview. And those who don’t are not going to be reconditioned to think or believe otherwise by anything I might write, or do.

Every day that I post a new article, I lose another reader who is annoyed at the apparent incongruity or cognitive dissonance of my writing, and I pick up a new reader for whom what I say is seemingly less incongruous than everything else they’re reading.

Still, just writing about all this never seems like ‘enough’. I feel bad mostly because I’m not doing anything about the local aspects of, and local contributors to, collapse — incompetent political decision-making and spending decisions at every level, insane development proposals, the clear-cutting of mountain forests and rezoning of rich agricultural land for new housing, the horrific conditions of the local homeless population, the ever-growing number of instances of family, and animal, abuse and neglect, and the endless firehose of propaganda that permeates everywhere, including local media. Even here.

I decide that I’m going to find one thing I can do that will make a difference, locally, something that doesn’t depend on changing people’s minds. Maybe volunteer to help clean up or test the water of our local creek. Or organize a fix-it fair. I don’t know. I’m so unskilled at doing things that are useful in a world falling apart.

My quest today for sights and sounds of joy, pleasure and fun is not to valiantly seek these things ‘in spite of everything’, or to escape from the drumbeat of collapse and the doomscroll. The feral creature in me just wants a break from what seems to me the terrible drudgery of the human condition — so many humans I know seem to live lives largely devoid of joy, pleasure and fun, and full of unhappiness, and steeped in fear, anger, hatred, sadness and trauma.

I could say things “shouldn’t” be this way, but it’s not as if it was anyone’s choice. This is how it inevitably is. Still, today I want to suss out pockets of human and more-than-human life that are ‘uncivilized’, untamed, pleasure-filled, joyful — creatures at play, having innocent, harmless, even silly fun. The wondrous delight of discovery and exploration, for its own sake.

I look at the ducks for inspiration. There are about 60 of them here, mostly huddled closely together, moving away from the shore when a dog or child or loud person moves too close to them too quickly, and then meander back, moving as one. Ducks sleep with one eye open, and one half of their brain alert, to detect any danger, and in a group it’s the eye closest to the outside of the group that’s open. The ducks in the middle of the group are lucky; they have both eyes closed.

When I look at their eyes, I notice that they have dark sclera (the “whites of the eyes”) indistinguishable (to humans at least — ducks have vastly better vision than humans in many ways) from the cornea. I remember reading that the only animals that have evolved relatively large white sclera are those that move and hunt in packs (humans and our ape cousins, and some canid species), and the speculation is that our sclera evolved that way to make us visible to our group at a distance and to enable us to silently communicate in ways that benefit the collective effort.

I listen to the voices of the people going by in their circuits around the lake. I turn, I hope discreetly, to look at their faces. I would guess that about half of them seem to be having fun. Either their vocalizations are animated (not necessarily loud, just varied in tone), or they are smiling. This is hardly ‘nature’ and hardly an adventure, but still, there is evidence of joy here. Those walking solo are harder to gauge; they mostly look to be caught up in their own thoughts, but there is another clue — the whites of their eyes. When their eyes are animated, my instincts tell me, for the most part, they’re enjoying themselves. Maybe when we’re enjoying ourselves, we are paying more attention, noticing more, and that shows up in more eye movement, even when the eyes are mostly downcast. Just a guess.

I have often hypothesized that wild creatures basically live in three ‘states’: equanimity, excitement, and stressed. This is based entirely on animals I have personally lived with. Most of their lives, they seem to be equanimous — just at peace with the world. Excitement is provoked by various things — eg meeting another creature, sniffing something interesting, or a conditioned association (eg the promise of imminently going for a walk or a car ride). The stress state is (for untraumatized animals anyway) seemingly temporary and anomalous. Under stress, the creature ‘snaps to’ a state of heightened awareness, and presumably adrenaline production, to be able to react quickly to the sources of the perceived stress, and then ‘shakes it off’ when the source of the stress has passed. Civilized humans, I suspect, spend most of our lives in this unpleasant and (IMO) unhealthy third state.

The ducks seem, mostly, to be in their equanimous state, while the dogs passing by seem mostly excited. Equanimity seems to me a rare state for humans, though of course we can never know what state another is really in or what it’s like to be them; they may not know themselves. So it is kind of nice here where the predominant stressed state of our civilized world seems rarer, and where examples of equanimity and excitement are here to observe, to inspire us, and, of course, to serve as fodder for blog posts.

As I watch and listen to the people and animals, I wonder which of them have a “separate self” — a sense of themselves as separate from everyone and everything else. The radical non-duality speakers I know assert that that sense ‘no longer’ exists there, and that it was never needed in order for the apparent body and character to ‘function’ perfectly well, since it has no ‘choice’ in what is done anyway. And they also assert that humans are (to ‘them’) clearly the only creatures bedevilled with this sense of a “separate self”.

It makes sense to me that the ducks and the dogs have no separate selves, and no need of them. Their apparent lives are lived “full on” without the veil of self. There is equanimity, excitement, stress, pleasure and pain ‘there’, feelings that are fully ‘felt’, but not through the veil of a separate self. I get a similar sense from the babies in strollers I see — just that look of wonder, of taking everything in without taking it ‘personally’. Of course, that may be just what I want to believe, a projection, given my current fascination with radical non-duality. What stays with me is not so much whether these creatures have or don’t have separate selves, as that there is no need for separate selves, no need for the conception of one’s self as apart from everything else, in order to be fully functional.

Nevertheless, those old enough to walk and to ask “why” seem to be ‘full of themselves’, not only ‘cognizant’ of having separate selves, but quite preoccupied with them. This appears to be true even for those who seem to be in a joyful (excited or equanimous) state. So, for example: a pair of teenaged girls talking and laughing animatedly as they walk; a guy jogging around the lake with a huge smile on his face; a young couple clearly flirting; a woman practicing yoga; an older couple holding hands just taking it all in; a woman pushing a stroller and walking a dog at the same time, evidently enjoying talking with both the baby and the dog. Lots of moving sclera visible on these faces.

The rest of the humans don’t look very happy. What most distinguishes them is that they are not paying attention to their immediate surroundings. They are, evidently, either lost in their heads or lost in their earnest conversations. I would surmise that they are, like me most of the time, in what might be called ‘conceptual’ mode rather than ‘perceptual’ mode. The thing about perceiving, it seems to me, is that it takes you ‘outside of your self’. There is that brief space when the brain is apparently preoccupied with sensing, rather than making sense.

It occurs to me (now clearly in ‘conceptual’ mode) that there are two kinds of pleasure: pleasure that relates purely to excitement of the senses (the “spell of the sensuous”); and pleasure that relates to excitement of the ‘mind’, such as a new and intriguing intellectual ‘discovery’ or a reassurance that what one thinks does indeed ‘make sense’. The first is perceptual, the second conceptual. The first, I am inclined to believe, requires no conception of one’s self as real and separate; it is a direct stimulus/response process. It is what we see, I believe, in wild creatures and in babies, and in other people when they are paying attention to sensory stimuli and not to what those stimuli ‘mean’.

The second does require the conception of one’s self as real and separate. When we learn something new and interesting, or when we laugh at a joke, or when we discuss something abstract, the pleasure comes from ‘making sense’ of things. The astonishing corollary is that nothing makes sense and nothing has to make sense if there is no separate self to make sense of it — it just is as it is (apparently).

But some learning does seem to be ‘self-ish’: Surely animals like young foxes and crows (and maybe ducks and dogs) ‘learn’ through play and trial and error, and that must mean they have a sense of self that motivates this learning behaviour? When you watch a bird poking vigorously at a potential food reward with a stick, surely it is doing this for its ‘self’?

Well, actually no. In all creatures, dopamine appears to be what drives us to learn, and to play (and to do lots of other things). That dopamine evolved in our bodies to condition us to learn and play, because those things are important for survival. The dopamine is produced, in all creatures, to make us feel happy in anticipation of a reward. We have no choice but to enjoy learning and playing. That’s the same whether it’s the young fox learning motor skills playing with a bone, or the young video-game addict playing the latest RPG 18 hours a day, or me, finding more scientific evidence that supports belief in no-free-will and radical non-duality.

‘We’ don’t do anything. ‘We’ are done to, by our conditioning. Having a sense of self and separation has nothing to do with it.

With that grounding (or conditioning) I now cannot help but ‘see’ dopamine driving all the behaviours I see: Floods of it in those that are in a state of excitement. A steady trickle of it in those in a state of equanimity.

As for those in a stressed state, dopamine apparently plays an important but subordinate role to other biologically-induced chemicals that arise in all creatures in stressful moments of fear, anger and grief. Adrenaline, cortisol and corticotropin are some of the main chemicals involved in conditioning us to become angry, fearful or sad, and they all immediately prompt the production of extra dopamine to keep us in that highly emotional state, even ‘hooked’ on it, at least until the event that produced that conditioned response has passed. Anger is not just a ‘mask’ for fear; the two feelings are synchronously evoked in us by the same chemicals.

…..

The couple flirting are showing the most scleral activity, notably the sidelong glances that maximize the amount of sclera displayed. I remember watching an interview with Canadian singer Shania Twain where she seemed to deliberately cast a lot of sidelong glances, and being aware that I was quite taken with this body language. Yesterday, I watched a couple flirting in the local café — same eye inflections, same active sclera display. No choice in our propensity to do this, or in how we respond to it, I’d guess: A veritable exudation of dopamine.

Hard to read the man smiling as he jogs around the park. I’ve never experienced “runners’ high” but scientists say it’s the result of the body’s release of endocannabinoids, anxiety-reducing hormones (also released during orgasms and when eating dark chocolate). He looks like a serious runner. My experience is that the pleasure kicks in after your exercise, which I’d attributed to the “checked that off the list” sense of gratification, but which might just be more chemicals dictating my feelings. I wonder, since I really dislike running (it’s boring and tiring), what it is that has conditioned me to do it with such rigour. I ascribe this diligence to fear of getting injured or ill or fragile if I don’t stay in shape, and of course to vanity, but it’s more likely that body chemicals are behind it all. I’m basically lazy, but still seem to do this workout whenever I lack any good excuse not to.

The two teenaged girls laughing and joking are a joy to watch. Feeding off each other’s pleasure, apparently acting out in an exaggerated manner the behaviour of a mutual acquaintance. Ridicule is often mean-spirited, but in them it seems mostly good-natured, a gentle caricaturing. In all our conversations and interactions with others, we are acting, performing, but when we are doing so deliberately it seems a particularly delightful form of play. The play’s the thing, and we are playwrights all. Ask any actor or musician about the chemical rushes that drive and accompany a performance.

The woman doing yoga has her eyes open. Her expression conveys an intense focus, perhaps remembering a specific sequence and duration of poses, or the timing of her breath. Why is she doing this here, rather than in a less distracting place? She had no choice in this, of course. Perhaps it, too, is a public performance, or a reenactment of some previous yoga practice in this same place that was especially pleasant or effective. Or perhaps the presence of this sort-of natural place helps her get ‘outside’ herself and whatever has been preoccupying her mind, which helps in her meditation practice.

The older couple holding hands are gently pointing things out with their unoccupied hands. Maybe they can’t see or hear as well as they once did, so they’re helping each other out with the details. Or maybe they’re recounting some memory of this place or someplace similar. Everything about their body movement and language is so different from what I’ve observed in couples that are talking about some ‘internal’ thing, something that is not-here-now. When we are paying attention, it seems, we are somehow less our selves and more a part of everything else, like the ducks.

The woman chatting back and forth to the baby and the dog, I surmise, is inadvertently teaching the baby about the meaning of ‘self’ and of ‘other’, showing her how to become comfortable with the dis-ease of separation that will afflict her the rest of her life. She is interpreting what she imagines the dog is thinking and feeling and ‘saying’ to the baby, modelling the art of ‘self’-expression and of conversation with another creature. The baby is delighted, laughing, reaching for the dog, prattling on incoherently. The scene fills me with joy for what is being discovered and found, and with sadness for what is being lost. Lots of dopamine for the woman, the baby, and the dog, who jumps up and takes a treat for being a “good dog”.

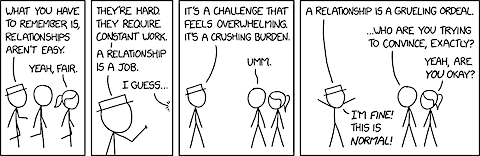

Not much to say about those circling the lake in a clearly stressed state, those taking in nothing of this beautiful, if artificial, place. Most of us with ‘selves’, I suspect, spend most of our lives in that unpleasant state. I think the chemicals that alert wild creatures to dangers and prompt a conditioned fight/flight/freeze response for brief moments, are coursing through our veins for most of our waking hours, every day. There are only rare respites, like when we fall in love, when we get a brief reprieve from the debilitating, exhausting, endless flood of chemicals keeping us constantly, and mostly unhelpfully, hyper-alert. When we fall in love, the sense of our all-important separate self briefly falls away and opens us to something larger.

That of course is all about chemicals, too, the flood of substances that condition us to sacrifice our selves for something more important, to give up our freedom, to become attached. These are the moments when it is most clear that our ‘selves’ never had any say, any choice, over anything. ‘We’ have never done anything. ‘We’ are done to by our conditioning.

Losing themselves in the rush of chemicals that conditions our every move is simpler for wild creatures, who I think lack the sense of, and belief in, themselves as separate and apart from everything else, and the illusory sense that there is a ‘self’ somewhere inside their body that has, or ‘should have’ control over these actions. Only humans feel remorse for doing the only thing that they could ever have done.

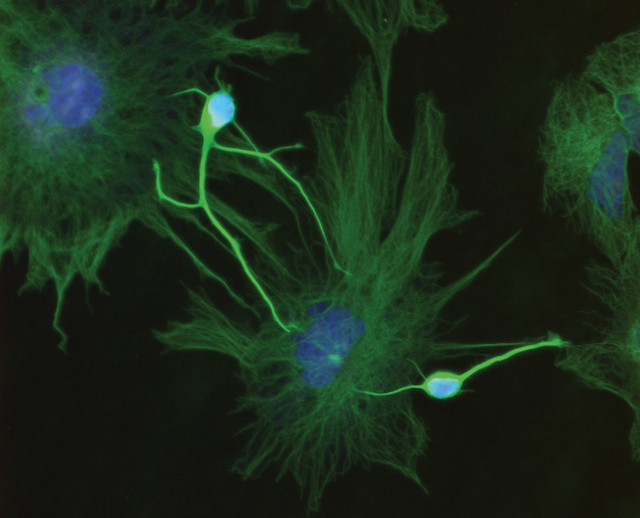

And it’s even worse than that: There actually is no duck, no baby, no couple flirting, no ‘you’, no ‘one’, nothing ‘singular’. These are just labels, names we apply to an only-apparently-cohesive complicity of trillions of creatures that seemingly ‘make up’ a living creature. ‘We’ aren’t conditioned, this complicity is conditioned, and ‘our’ apparently conditioned behaviour is the aggregate result.

So I look again at the ducks, the dogs, the babies, the people who are under the spell of the sensuous, and those who are not. They are all complicities, just labels we arbitrarily apply because the reality of the complexity of trillions of moving parts without tidy boundaries and borders is more than we can fathom. Without these enormously oversimplifying labels, we cannot ‘make sense’ of anything. As John Gray has put it, we labour under the illusion that we are “all of one piece”, when we are not.

Now, rather playfully, as I sit here looking toward the lake, I try to no longer see animals and people and trees and buildings as single ‘things’, but rather as a profusion of vast complicities of trillions of creatures and waves and particles (and other components with apparently no substance at all), with each tiny component being constantly conditioned in unimaginably complex and mysterious ways by trillions of other components. There is no ‘one’ here. That was just a trick this brain played, conjuring up and labeling things hypothetically to try to make sense of what cannot be made sense of. Of what need not be made sense of.

For now, I put out of my mind the tragedy that the illusion of the self and separation has seemingly led to — the altered chemistry of humans and the chronic mental illness and violence that that evolutionary misstep has apparently produced. At this moment, it’s too much to bear, especially the knowledge of its inevitability.

Instead, I watch the ducks, the dogs, the babies, the flirting couple and the other humans paying attention or lost in their thoughts, not as entities but as just parts of the utterly interconnected and inseparable chaos (etym.: ‘vast openness’) of everything that appears to be. Just this, in all its wonder.

I think the ducks ‘see’ this. I smile at them, and they look at me curiously and equanimously. Quack.

I can’t help but think: If only… But no, that’s foolish grown-up human thinking.