collage of logos of mainstream media by EJN (“what we really need in our profession are more skilled reporters”; “stories are the programming language of humanity”)

My first inkling that private and state-owned western media were being played came during the Gulf War, when it was revealed (but only to those paying attention) that the global PR firm Hill & Knowlton, hired by the government of Kuwait and sponsored by the American military establishment, scripted and presented a completely fictional account of Iraqi “atrocities” in Kuwait, complete with teary paid actors talking to members of Congress.

This charade was “bought” and presented as “facts” justifying the invasion of Iraq by all the western media, without exception, and even by Amnesty International (they later retracted their support). It was a slick production. No one was ever prosecuted for this crime, and it was just enough to convince the US to attack Iraq, with devastating and continuing consequences. Hill & Knowlton continues to operate today.

I have always been aware that warmongers, to garner political support (mostly by slandering “opponents”) and to reap profits for their corporations (mostly in the military-industrial complex), have been using massive and carefully-scripted disinformation campaigns for decades. But I mostly figured the western media, supposedly trained journalists, would at least uncover, discredit and refuse to report the most egregious examples, if for no other reason than to protect their citizens from being plunged into dangerous wars and other reckless and ill-founded military and espionage misadventures by disinformation.

But now I think I was naive. The media, increasingly starved for resources needed for real investigative journalism, and staffed with young, under-experienced and credulous “reporters” have been outgunned at every turn by massively funded, professional PR firms, “reputation management” organizations, extremist pressure groups and their military-intelligence-industrial funders. They have become, unwittingly, mouthpieces for these propagandists — they simply don’t have the smarts or the deep pockets to be anything else.

The latest case in point is yet another Sinophobic article, this one by the CBC’s supposed investigative journalism program Marketplace. The thrust of the piece is that we should not buy tomatoes that might have been produced in China because to do so is supporting Uyghur genocide. (Thanks to Caitlin Johnstone for the link.)

If you have the time, please look at this YouTube video, by a Canadian who lives in China, deconstructing the Marketplace article piece by piece, and in the process, showing just how modern propaganda is made, using western media as unwitting dupes. Again, there are standard scripts, professional actors used again and again, and a pre-developed conclusion (“China is evil; don’t buy their tomatoes”) with the sound bites and “facts” (though none of them is stated as a fact, and none of them is supported by a shred of evidence) carefully tailored with the appropriate hyperbolic tone to “support” this conclusion.

Watching it was enough to make me ill. The CBC’s journalism was so sloppy, and so credulous, that it borders on complicity to deceive Canada’s citizens and taxpayers.

And we are now being bombarded with this slick propagandized nonsense at every turn:

- We are being told that Russia plans to invade “our ally” Ukraine, and that “international war is almost certain”, when even the Ukrainian government is telling the western media to stop wildly exaggerating the events and threats — to stand down and let the two countries deal with their own issues.

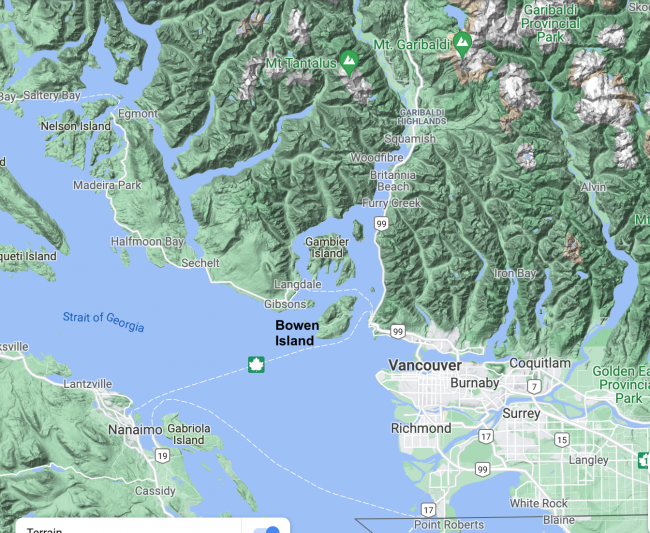

- We are being told that China plans to invade Taiwan and that if we don’t intervene, “Australia will surely be next”. Both claims are absurd. The international status quo remains that Taiwan is a part of China, and has never been an independent country, and that it operates with great autonomy, and that this status quo is absolutely in the best interests of both Taiwan and China. But the propaganda machine would have us believe that the Chinese are “termites” bent on destroying the US in their quest for world domination.

- We are being told that all criticism of Israel’s occupation of Palestine and its program of apartheid, is racist antisemitism that is necessarily an attack on Israel’s very right to exist and must therefore be squelched.

- We were told of brutal atrocities committed by ISIL in Syria against its own citizens, with the gullible NYT running a whole (award-winning!) podcast series “Caliphate” about an ISIL “executioner”. But then we found out it was all made up. The NYT claimed to be a victim of the fraud and made no apologies for their shoddy research.

- Before that we had the nonsense about Russian troops paying the Taliban in Afghanistan a bounty for “American heads”. We had endless reports about how evil the governments of Venezuela, Cuba and Syria are. And of course Iran’s plan to develop nuclear weapons for offensive purposes.

No wonder so many of us are skeptical of what we’re being told, when our “trusted” media are being so easily and totally played by propagandists!

I am not of course saying that the governments of Russia and China (or any other country) are completely innocent and above criticism (In fact Vladimir Putin has used Hill & Knowlton to do some of his US-based lobbying). I am merely saying that the recent scare-mongering about them was concocted and/or wildly exaggerated by deliberate propaganda campaigns by vested interests using western media as their hapless mouthpieces.

Who stands to gain from this?

- Both the Republican and Democratic party establishment in the US, and their counterparts in other western nations. Fear-mongering, warmongering and sabre-rattling are proven, highly-effective distractions from domestic bumbling, corruption, haplessness, and news of domestic social and economic upheaval and anger.

- Big corporations — not just the military-industrial complex, but other industries like Big Tech that benefit from increased paranoia and defence and “security” spending, and industries like Big Oil and Big Ag that benefit from the endless smokescreen of invented crises that keep their own misdeeds out of the headlines and hence out of public scrutiny and outrage.

- The propaganda industry — the massive PR and “reputation management” firms, the out-of-control, secretive “intelligence” bureaucracies, and the extremist media, whack-job podcasters and pundits and nut groups like QAnon that gain supporters and money from spreading and capitalizing on fear, misinformation and disinformation.

I don’t believe that the so-called “mainstream” western media actually benefit from this propaganda. They are simply clueless tools, taken in, desperate for a story that will stave off their demise for another day. The slicker and scarier and more righteous-outrage-fomenting, the better.

One of the “big” news stories in Canada these days is the trucker convoy that has “occupied” Ottawa and disrupted traffic in other cities. They have raked in $12M by duping GoFundMe when they claimed that they were a “charitable” organization. They’re serving as a money-funnel for American right-wing groups to play dirty in someone else’s country, and have also been funded by Alberta separatist groups. They have managed to offend Ontario’s and Alberta’s Conservative governments with their noisy, disruptive, and highly-polluting display, and even managed to topple the country’s federal Conservative party leader, who tried to stay above the fray and didn’t support the convoy, which “demands” that the government immediately end “all restrictive public health measures” nationally (though most of them are under provincial authority), along with more ludicrous demands. His successor, not surprisingly, “supports” the convoy.

They’re not the brightest bunch (you gotta shake your head when some of them arrived carrying confederate flags and Trump and QAnon signs), and they have clearly been effectively propagandized, and their fears and hates preyed upon, by political opportunists inside and outside Canada.

But although they’re a pain in the ass, what they’re doing is not, strictly speaking, all that different from, or much more disruptive than, what the Occupy movement did in its day. So, unlike most of the people I know, I don’t think the answer is police or military intervention. Of course convoy members who break the law should be singled out and fined, or, in the rare cases where they have threatened or harmed Ottawa’s citizens, criminally charged. But rendering a protest action illegal because it blocks traffic, even for a lengthy period of time, is a slippery slope.

I do feel for the citizens whose lives and livelihoods have been disrupted, and hope this ends soon.

But the western press has just drooled over this story, suggesting that it “threatens Canadian democracy”. Meanwhile, they stay carefully mum about the fact that real investigative journalists like Julian Assange rot in jail for revealing the truth. And meanwhile, real news like the western-backed war in Yemen that has cost millions of lives and caused untold suffering, drags on, almost entirely unreported.

We can’t “fix” the media, and there is not enough money in mainstream journalism today for proper hiring and training of journalists, or even a modicum of competent screening of falsehood from truth. And meanwhile, the political and corporate financiers of disinformation and misinformation have extremely deep pockets for deploying falsehoods.

The only thing we can do, in the face of this, yet another modern tragedy of a civilization in collapse, is to challenge everything we read and hear, insist on credible, corroborated evidence, and simply turn off media (including social “media”) that fail to demand hard evidence from their “sources” and hence inevitably fall victim to propagandists.

As Caitlin Johnstone, who has long been shouting about this subject and the dangers it poses to us, says, citing Christopher Hitchens: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”

And should be.

I hope the remaining competent journalists at the CBC, who are having a particularly bad year, are able to find new work with a more credible media organization (there are not many left). And that the rest of them learn how to do their jobs.