New Yorker illustration by David Hornsby

“I remember a time when everybody knew their place. Time we got back to that.” — supporter of the incumbent American president the day after the 2016 election, cited in Caste

Our universal propensity to think in the short term has a lot of people hoping that Trump will lose in November, even though a lot of them don’t think much of the alternative, vowing to fight on for progressive causes no matter which old white male conservative candidate wins.

There’s a kind of collective holding of breath going on, as if there is a huge proportion of undecided voters up for grabs if something ghastly happens between now and then (according to recent polls that proportion is already less than 5%), or of course if the election is stolen, as it has been before.

What I find most alarming is the wishful thinking behind many progressives’ feeling that if Trump loses, we’ll never see him or the likes of him again. That was what many said once de-facto-President Cheney’s puppet regime’s term ran out.

This is dangerous thinking. Opinion polls consistently show that Trump’s support among white males remains basically unchanged over the past four years. This, not Republicans, is his real base — a clear majority of white males continue to support Trump, and it hasn’t been that long since they were the only people allowed to vote. Whites, and male whites moreso, have voted against every Democratic presidential candidate since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

And let’s be clear — I didn’t say old white males. Young white males of all voting age groups remain committed, almost as much as their older counterparts, to supporting Trump. Their entrance into the voting age cohorts has barely caused a ripple in the plurality of white males supporting Trump. That may surprise you until you consider that a disproportionate number (about half) of young voters are non-white (only a quarter of boomers are non-white), so looking at the entire youth cohort’s seemingly progressive attitudes obscures the reality that most young whites hew to the same extreme right-wing politics that the majority of old whites subscribe to; there’s just fewer of them.

And for a whole host of mostly disgraceful reasons, mostly to do with deliberate disenfranchisement (by white males), white males are the American demographic cohort most likely to vote.

What does it tell you that a majority of white males of all ages are knowingly prepared to vote again for a candidate who is blatantly corrupt, a pathological liar, clearly mentally deranged, uninformed, racist, sexist, utterly unprincipled, and staggeringly incompetent?

Think about that. What does it tell you when this is the case in a supposedly democratic, free, educated nation?

If we catch a break and he loses despite this rock-solid and immovable base, what then? Do we really think white male Americans are going to see the light and wise up? Four years from now, even if Trump loses, we’ll be lucky to have made a start at undoing the damage he has done, let alone starting to address the blizzard of crises that Trump has ignored or denied, at his country’s and the world’s peril, over the past critical four years. And we’ll then have to fight the battle all over again, with the odds still and always stacked against us.

The US has a long-term problem, and it’s white males — a significant and hard-core majority of them. What is the world going to do about them? Trump may lose, and, if we’re lucky, may even go away. But white American males aren’t going anywhere. They stand between the rest of the world and any hope of mitigating the mounting catastrophes that we’re going to face in the coming years and decades. Our systemically racist, sexist, patriarchal culture has produced them, and their attitudes, and is still doing so. It is not getting better. White male voters tend to get even more conservative as they get older.

Of course, in addition to massive and increasingly overt disenfranchisement, the American patriarchy has invested in other anti-democratic measures like the electoral college to deprive the majority of their choice for president, an absurd system that gives Wyoming the same representation as California to subvert the will of the majority in the Senate, and computer-perfected gerrymandering to ensure white males continue to control the House. With this control of the executive and legislative branches, they also control the courts, the legal system, and law enforcement, which are created in their likeness to support and preserve white male power.

Is there any hope of this being reformed, and soon, so that the US can join common cause with the rest of the world in tackling all the important issues at hand? Issues that white male American exceptionalism has spurned.

I see no reason to be hopeful.

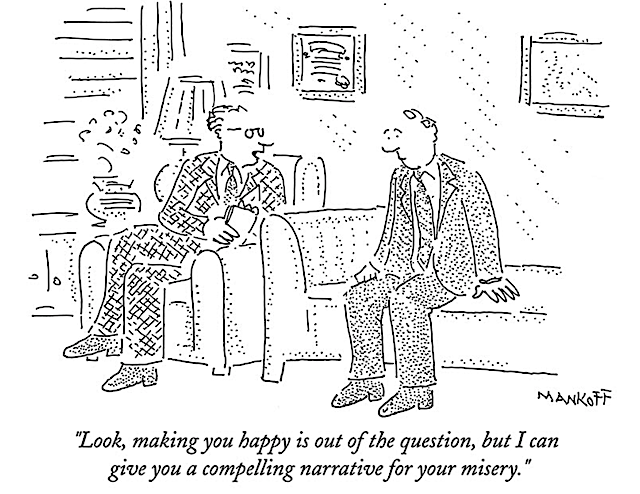

I don’t lay any blame, though. I’ve studied enough history to understand the appeal of brutal authoritarian populism to people who, by virtue of their hopeless situation in a nation where median income is falling, median net worth is negative, and the middle class has substantially disappeared, are filled with rage, shame, and a sense of impotence — a sense that the “ruling class” (the universities, the media, the professional class) cares nothing about their situation and largely disapproves of them (remember “deplorables”?).

It is not therefore surprising that someone who pretends to thumb his nose at the establishment, who speaks about everything as if it’s dead simple black and white, and who is so bumbling and incoherent that he can’t be intimidating, could be seen as their champion.

Of course, many BIPOC people have been treated much worse in what has become the third-world economy and rigged politics of the United States of Inequality, and their rage in the streets of America is perfectly understandable.

History is replete with examples of citizens electing autocrats who threaten the ruling class when the ruling class disregards them long enough. It is also interesting to note that these revolutions and usurpations of power are usually launched not by the poor, who have lived with oppression all their lives, but by the newly impoverished, often members of a middle class in decline, who feel that their ‘caste’ rating in the society has fallen, and unfairly so. Hitler and Stalin benefited from this, as Trump is now.

Isabel Wilkerson’s extraordinary book Caste outlines how our implicit caste system works. It suggests that over time all North Americans of European ancestry have been melded into a single dominant ‘white’ caste, with Asians, Latinos, Indigenous peoples and new immigrants from the African continent as the middle caste, and Blacks remaining, as they have been since their ancestors first arrived, as the lowest, subordinated caste.

While I agree with just about everything in her analysis, I think our caste system is actually more complex than this. I would suggest that in parts of North American society Asian-Americans are treated as belonging to at least three and possibly more castes depending on where in Asia (Mid-East, South Asia, East Asia) they or their their ancestors came from. I would suggest that First Nations people are, in some places in North America at least, treated as a subordinated caste.

And I would suggest there are at least a dozen ‘white’ castes, of which privately-schooled, healthy, wealthy white males whose descendants have been in the country over a century are the top caste, and various other whites rank variously lower depending on whether they are male or female, how old they are, whether they are poor, whether they own their own home (or rent, or are homeless), what schools/universities they and their children attended and currently attend, what degrees and professional credentials they have, whether they are (physically and mentally) healthy (and if not, whether their illness is seen as a disease of the privileged or of the masses), how long their ancestors have been in the country, and their sexual orientation, speaking accent, religion, club memberships, and even appearance (fitness, level of beauty, dress and behaviours).

I do agree with Isabel* that Blacks (African-Americans) were and are treated as the bottom, most subordinated caste, wherever they live in North America. In geographical areas I have lived in that have almost no Blacks, another group, usually but not always what Canadians call a “visible minority”, seems to be treated as the most subordinated caste. Over the course of my life, that has at one time or another included Jews (who for many years could not join certain clubs), immigrants from Eastern Europe, immigrants from South Asia, First Nations peoples, people in the LGBT+ community, and those with physical and mental challenges. It seems that some group has to be identified as the lowest-ranking caste, to provide the basis for self-identification for everyone else.

I would also say that many white Americans automatically (and mostly subconsciously) treat all non-Americans as being of a somewhat lower caste than they would be treated if they were Americans, all other things being equal. They do so usually politely (depending on how low the caste they’re interacting with) but often patronizingly. I think that is the main reason so many Canadians, often unconscious of our own caste, distrust and even dislike Americans who force us to realize how utterly baked into our culture caste-ranking is — and they show us by slighting us. Ask any Canadian who works for an American boss if you doubt me.

In her book, Isabel describes the astonishment and outrage that a white dinner companion expresses over how they were treated (presumably because of Isabel’s presence) by staff in a restaurant. She tells her companion that if a Black American were to get outraged every time they were so treated, they “wouldn’t last very long”. She wishes that everyone could have a taste of this, just so they would know how it feels.

As a white male, I have been buffered from such treatment most of my life. I have been mistreated on rare occasions because of my long hair (especially in the 1960s and 1970s), how I have dressed, and due to my ‘radical’ politics. But these were conscious ‘misbehaviours’ on my part, and I was prepared for what they provoked. The only occasion when I was truly aware of how others perceived my caste rank was on a business trip in the 1990s. Flying in business class (a last-minute upgrade using frequent flyer points) I found myself seated beside one of Canada’s ten wealthiest men (the wealthiest were of course all men, and all white, as is still the case). He looked with obvious disdain at my casual attire, as if I were letting the side down. When I introduced myself and told him my (executive) title, he seemed surprised. He didn’t introduce himself, but instead asked me what schools I’d gone to growing up. When I told him public schools, he cut me off, ‘apologized’ that he needed to catch up on sleep for an upcoming business meeting, and turned his face away from me for the rest of the flight.

Rather than outraged, I was completely bewildered. I had no idea that such a caste system existed in Canada. Curious, I talked to others and discovered it was well-entrenched, and in my relative privilege, I had simply been oblivious to it. I hadn’t wanted to be aware of it; I didn’t want to believe that anyone treated people differently, in any systemic way — not here, not today! How un-Canadian! [The existence of different “classes” of travel, with their private segregated bathrooms, the unapologetic use of that term, and the different treatment afforded lower-class travellers, speaks volumes all by itself].

So then, in my forties, I suddenly became aware of the presence, effectiveness, and power of the caste system, and how utterly Canadian it actually was.

Fifteen years later, I went to visit the late Joe Bageant in Belize, and he gave me a crash course in how well entrenched the caste system was in the US. (The book he wrote, Deer Hunting With Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War, is IMO essential reading in understanding what he called the “white underclass” — the backbone of today’s Trump supporters.)

He was the one who told me about the pride and shame of what he called those of “mostly Scots-Irish descent” — whites whose ancestors didn’t think of themselves as white when they arrived (some of them as indentured servants), and who were treated for generations as lower- but not lowest-caste Americans (that position being already taken by African-Americans, slaves or not). Caste describes their delight at their apparent “upgrade” during the gradual merging of all white castes of European descent (even the then-despised Italian-Americans who made up most of the non-Black prison population in the early 20th century) into a single, dominant caste over the last century.

But then that pride turned to shame and anger as they found themselves seemingly downgraded in rank again, due to their poverty and lack of education, since the optimism of the 1960s yielded to the jaded materialism and defeatism that has prevailed ever since. Today, the members of the white underclass are the coal miners, desolating their own home communities just to make a buck. They’re the vast bulk of the military, the only means they can find to afford an advanced education. They’re the farmers, overworked and then robbed of their farms by Big Agriculture, often ending up working for the new owners of land that was once theirs. They’re the factory workers, with no opportunity for advancement, mistreated and tossed aside as automation, outsourcing, offshoring and union-busting provides arrogant and indifferent corporate executives (almost all of them white males of the top-most dominant caste) with a means of reducing costs. Their shame and misery is expressed in the astonishing number of them addicted to and dying from heroin, cocaine and fentanyl, as well as the old working class standbys, alcohol and tobacco, and the many other diseases of despair and hopelessness that have recently started to lower life-expectancies of this caste.

As the statistics show, it is now almost impossible to move economically from one quintile of income or net worth to a higher one, even over several generations. If “higher education” was ever a vehicle for doing so, it is no more. Since the death of egalitarianism and idealism in the mid-20th century, your wealth and education has become a lifelong badge of your caste, inherited and passed down to future generations. Poverty, and the rising chasm of economic inequality, have ushered in a subtler but still oppressive form of slavery, and while Blacks remain far and away the most oppressed caste, many working class whites have fallen from the dominant caste to something seemingly hopelessly below. They are angry (especially the gender with most of the testosterone). And, being uninformed and poorly educated, they are ripe for the picking by autocrats like Trump. And their shame and rage is often directed at — you guessed it — those of subordinate castes (in the corporate caste system it’s called “suck up; shit down” and it worsens as corporate size and number of levels of hierarchy increase).

This is classic scapegoating caste behaviour, and it is being perfectly ‘played’ by Trump and his cronies. It hurts to see the bitter irony of two struggling castes of Americans — Blacks and the “white underclass”, fighting each other in the streets, as members of the topmost dominant caste (the “1%”) cynically take sides and cheer on “their” side, the result being a complete distraction from the final looting of America’s remaining wealth by this caste — a dominant caste that doesn’t really give a damn about either side (even on voting day, since the dominant caste has long owned both parties).

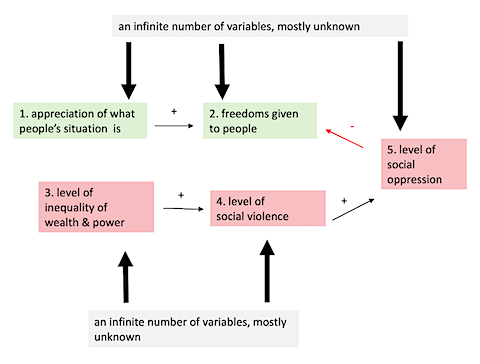

There is a ton of data showing an almost perfect geographic correlation between inequality and violence. As inequality spirals out of control in North America, so will violence, and the repressive militarized police-led bloodshed unleashed to suppress it. And guess who the police, which are largely comprised of members of the angry white underclass, are going to focus their violent suppression on?

Isabel writes: “Caste is insidious and therefore powerful because it is not hatred; it is not necessarily personal. It is the worn grooves of comforting routines and unthinking expectations, patterns of a social order that have been in place for so long that it looks like the natural order of things.” Said in different terms, we might say that the behaviours that arise from conscious or unconscious perception of the prevailing caste system are enculturated conditioning. If that is the case, then we really have no choice but to act, often badly, in accordance with this conditioning. This isn’t an excuse for it, just an explanation. Hopefully, over generations, we might begin to socially condition each other differently, with greater awareness of the inherent injustice of caste-driven behaviour and less judgement, discrimination and damage to the victims and to the entire social fabric of our communities. To do so will require an end to the de facto segregation of castes — We most fear, misunderstand and distrust those we have never met, never spoken to, never worked and fought alongside.

Of course, there is the huge question of whether or not we can afford to wait for that to happen. In light of the grievous level of inequality, especially in North America where it continues to accelerate and put more and more stresses on all but the top-most dominant caste, it seems more than possible that the social fabric of the country will tear before that happens, and civil war or fascist dictatorship will be the result. While this will be a war between castes, the racial divide in it will be clear. If it results in a fascist coup and dictatorship, the top-most white dominant caste will be torn, since the white underclass arguably despises them as much as they do the subordinated caste. Many in the top-most dominant caste prefer the reliable, less emotional Democratic Party it controls over the Republican Party it seems to be losing its grip on, though it still clearly controls most of both parties’ elected officials. But history tells us they are more likely to try to appease a fascist dictatorship than risk losing power by opposing them.

And it really is all about power, and the wealth and other privileges power affords. In his review of Caste, Indian historian Sunil Khilnani, wondering whether Isabel’s call for “radical empathy” may be naive, points out: “Changing power differentials in order to redress vile histories of discrimination [is always] bound to be ugly”. And as Frederick Douglass famously said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

None of this bodes well for the future of the rapidly-failing American state. Or for its oppressed peoples.

* Just a note here that I generally use first names, not surnames, when referring to writers and others in my posts, regardless of whether or not I know them personally. I do this regardless of people’s gender, race or perceived position. I choose to do this because I find referring to people by their surname to be both anachronistic and somewhat demeaning (it can also be confusing when referring to several family members sharing a surname in the same article). Using surnames with a title (Mr, Ms etc) seems absurdly formal. Using both given name and surname seems pretentious and redundant. I mention this here because in Caste, the author makes a point of how whites were encouraged to refer to Blacks, even those much older than they were, by their first names, while Blacks were expected to refer to whites of any age by their title and surname. I mean absolutely no disrespect in continuing my naming convention in this article, and apologize if any offence is taken by such usage.