Too many links already to wait for December, so here’s a special monthly edition of Links of the Quarter. Warning for the soft-hearted: There are at least five tear-jerkers in these links.

PREPARING FOR CIVILIZATION’S END

award-winning photo by Turkish photographer Ílhami Çetin; the story of 83-year-old Ali Mese and his kitten Sarikiz has a happy ending (thanks to Salome Tetiashvili for the link)

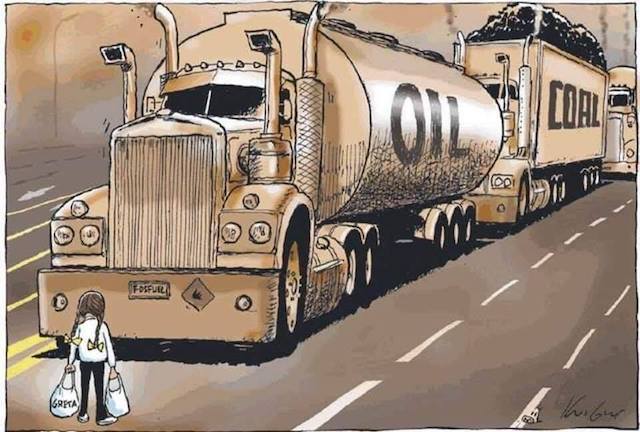

Robert Jensen on Collapse: My opinion on Robert keeps changing; sometimes he seems so depressed he becomes incoherent and maudlin, but in his recent, mostly-positive review of Naomi Klein’s new book On Fire (for Common Dreams), he’s right on the mark, and provides a cogent critique of the entire environmental movement, including the Green New Deal, and suggests where we should be focused instead. Here are some excerpts, but read the whole thing:

At the conclusion of [the book] that bluntly outline the crises and explain a Green New Deal response, Klein bolsters readers searching for hope: “[W]hen the future of life is at stake, there is nothing we cannot achieve.” It is tempting to embrace that claim, especially after nearly 300 pages of Klein’s eloquent writing that weaves insightful analysis together with honest personal reflection. The problem, of course, is that the statement is not even close to being true. With nearly 8 billion people living within a severely degraded ecosphere, there are many things we cannot, and will not, achieve. A decent human future—perhaps any human future at all—depends on our ability to come to terms with these limits. That is not a celebration of cynicism or a rationalization for nihilism, but rather the starting point for rational planning that takes seriously not only our potential but also the planet’s biophysical constraints…

[The] key points Klein makes that I agree are essential to a left/progressive analysis of the ecological crises: First-World levels of consumption are unsustainable; Capitalism is incompatible with a livable human future; The modern industrial world has undermined people’s connections to each other and the non-human world; and We face not only climate disruption but a host of other crises, including, but not limited to, species extinction, chemical contamination, and soil erosion and degradation [DP: not to mention economic collapse]. In other words, business-as-usual is a dead end, as Klein [acknowledges]…

Klein does not advocate [technological] fundamentalism, but that faith hides just below the surface of the Green New Deal, jumping out in “A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,” which Klein champions in On Fire… But one sentence in that video reveals the fatal flaw of the analysis: “We knew that we needed to save the planet and that we had all the technology to do it [in 2019].”

First, talk of saving the planet is misguided. As many have pointed out in response to that rhetoric, the Earth will continue with or without humans. Charitably, we can interpret that phrase to mean, “reducing the damage that humans do to the ecosphere and creating a livable future for humans.” The problem is, we don’t have the technology to do that, and if we insist that better gadgets can accomplish that, we are guaranteed to fail…

The problem is not just that the concentration of wealth leads to so much wasteful consumption and wasted resources, but that the infrastructure of our world was built by the dense energy of fossil fuels that renewables cannot replace. Without that dense energy, a smaller human population is going to live in dramatically different fashion…

My answer [to the question of what is actually sustainable on our planet]—a lot fewer people [consuming] a lot less stuff—is adequate to start a conversation: “A sustainable human presence on the planet will mean fewer people consuming less.” Agree or disagree? Why or why not? Two responses are possible from Green New Deal supporters: (1) I’m nuts, or (2) I’m not nuts, but what I’m suggesting is politically impossible because people can’t handle all this bad news.

The Green New Deal is a start, insufficiently radical but with the potential to move the conversation forward—if we can be clear about the initiative’s limitations. That presents a problem for organizers, who seek to rally support without uncomfortable caveats—“Support this plan! But remember that it’s just a start, and it gets a lot rougher up ahead, and whatever we do may not be enough to stave off unimaginable suffering” is, admittedly, not a winning slogan…

I offer a friendly amendment to the story [Naomi Klein] is constructing: Our challenge is to highlight not only what we can but also what we cannot accomplish, to build our moral capacity to face a frightening future but continue to fight for what can be achieved, even when we know that won’t be enough.

Naomi Klein on Radically Overhauling Our Economy and Politics: In light of the above, here is an interesting chat Naomi Klein had recently with the Guardian (audio only, no transcript) on the scale of change demanded by the Green New Deal, and the requirement to couple it with social and ecological justice. (She quotes Gilets Jaunes protesters to French PM Macron: “You care about the end of the world; we care about the end of the month.” She says we have to find solutions that address both.) She also talks about the subtle link between the rise of ultra-right nationalism and the fear of environmental ruin (the Christchurch mass murderer blamed “immigrants” for, among other things, the destruction of the environment; and anti-immigration bigots attempted to take over the Sierra Club a few years ago). Worth a listen. She’s right, I think, in her diagnosis of the problems we face, but, as Robert Jensen says, terribly naive about how, and if, they can be addressed by political and economic reforms.

Yes, the Climate Crisis May Wipe Out Six Billion People: Vancouver professor Bill Rees goes through all the outraged responses to XR adviser Roger Hallam’s warning of the consequences of not preventing the current trajectory of runaway climate collapse, even those from scientists, and find that Roger’s estimate is probably about right after all. He concludes:

A more important point is that climate change is not the only existential threat confronting modern society. Indeed, we could initiate any number of conversations that end with the self-induced implosion of civilization and the loss of 50 per cent or even 90 per cent of humanity.

And that places the global community in a particularly embarrassing predicament. Homo sapiens, that self-proclaimed most-intelligent-of-species, is facing a genuine, unprecedented, hydra-like ecological crisis, yet its political leaders, economic elites and sundry other messiahs of hope will not countenance a serious conversation about it.

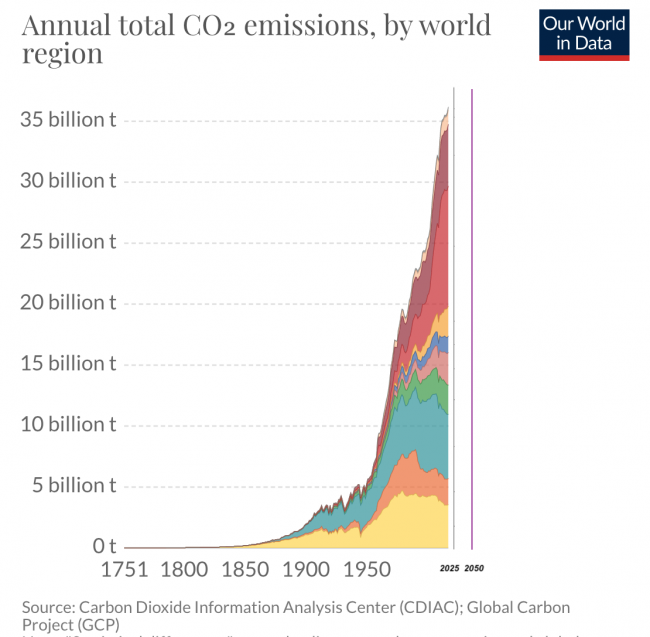

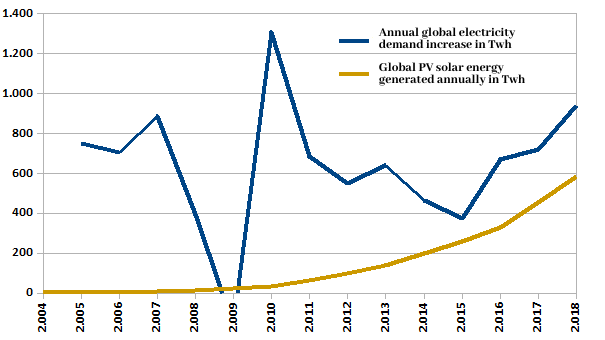

Jevons’ Last Laugh: The Jevons Paradox explains how, in complex systems, attempts to bring about change are almost always defeated by qualities of the system (“positive feedback loops”) that reinforce the status quo. So, as fuel-efficiency of cars grows, drivers subconsciously and guiltlessly drive farther than they would have before. When we try to find clean “renewable” energy, we find nuclear energy has fewer emissions but produces horrific radioactive waste that will outlast all of us and potentially kill far more than hydrocarbon emissions will, and both nuclear plants and fossil-fuel generating stations require vast amounts of water as a coolant. Hydro-electric plants, it turns out, have a large carbon footprint (especially their construction, and methane release) and are at risk of collapse when rain patterns shift, beside their impact on reducing water for other purposes, flooding reservoirs, disrupting fish habitats etc. And we’ve just learned that SF6, an artificial insulating gas ubiquitously used in electric transmission “switchgear” is a potent greenhouse gas, 23,000 times as disruptive as CO2, and its use is growing at 8%/year as we switch to more “renewable” forms of energy. There is only one way to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, and that is by consuming 90% less energy, starting more-or-less now. In other words, dismantling the industrial economy.

Canada Dithers as the World Burns: Canadians, terrified of electing another right-wing extremist Conservative government, held their nose and re-elected Trudeau, the guy who tries to please everyone and pleases no one. He’s a disaster, having reneged on the promise of proportional representation, and signed climate accords while buying a pipeline and reasserting of the ecologically ruinous Alberta Tar Sands: “No country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and leave them there.” (And it’s about to expand again). He waffled on right-to-die legislation that turned out to be so weak the courts have had to step in to assert this essential constitutional Canadian right to the terminally ill. Meanwhile his minority government can be propped up by either the Bloc Québecois (price of support: weakening of federal rights in favour of provincial self-management ie Mulroney all over again) or the NDP (price of support: impossible to tell, since leader Jagmeet Singh seems to be a man of great principle, but his caucus and provincial counterparts are reminding him never to put the environment ahead of jobs for the working class who elected him). The Greens fizzled late in the campaign to just 6.5%, due largely to an inept campaign by their incompetent leader and her right-hand man, the arrogant and equally incapable Andrew Weaver, who botched the proportionate representation referendum in BC when the Greens held the balance of power (giving up its opposition to the execrable and endlessly-litigatable Site C Dam), and purged the party of some of its strongest leaders over his vicious and pandering opposition to BDS. Weaver has just, mercifully, resigned, though it’s not clear if the party has anyone left who can competently take over. And the Canadian media shamefully refused to admit the sad truth that the collapse of the federal NDP to just 15% of the popular vote was mostly the result of racism. Bottom line: There is no real progressive party to vote for in Canada, and Canadians are simply not willing to do anything substantial to address climate collapse, beyond politely and quietly cheering Greta Thunberg and hoping she will fix it all for us.

LIVING BETTER

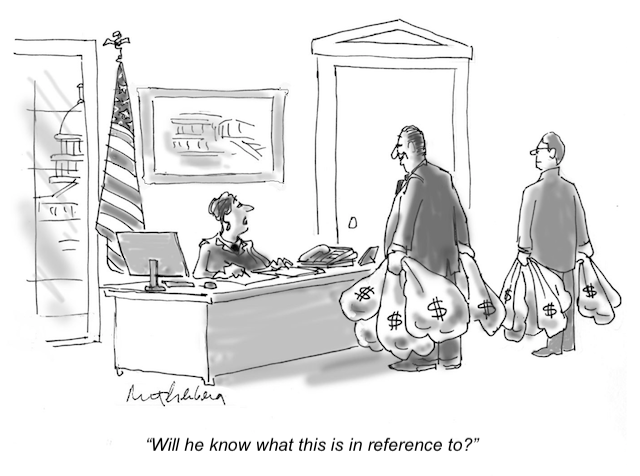

cartoon by Michael Maslin in the New Yorker

Let’s Tell Men to Lean Out: A recent editorial by Ruth Whippman in the NYT (sorry, behind paywall) suggests that too much emphasis has been placed on teaching and encouraging young women to “lean in” — to be more assertive, self-confident, skillful, forceful and unapologetic in putting their ideas, opinions and feelings forward; and not enough on encouraging men (of all ages) to “lean out” — listen and pay attention to what women are saying, and be less assertive, patronizing, inattentive, arrogant, and overconfident. “Women generally aren’t failing to speak up; the problem is that men are refusing to pipe down.”

On Empathy: A short, wordless film shows how we heal. Thanks to Jae Mather for the link.

The Carrier Bag Theory: Siobhan Leddy writes (Thanks to Jeff Aitken for the link):

The Carrier Bag Theory, an essay [Ursula] Le Guin wrote in 1986, disputes the idea that the spear was the earliest human tool, proposing that it was actually the receptacle. Questioning the spear’s phallic, murderous logic, instead Le Guin tells the story of the carrier bag, the sling, the shell, or the gourd. In this empty vessel, early humans could carry more than can be held in the hand and, therefore, gather food for later. Anyone who consistently forgets to bring their tote bag to the supermarket knows how significant this is. And besides, Le Guin writes, the idea that the spear came before the vessel doesn’t even make sense. ‘Sixty-five to eighty percent of what human beings ate in those regions in Paleolithic, Neolithic, and prehistoric times was gathered; only in the extreme Arctic was meat the staple food.’…

As well as its meandering narrative, a carrier bag story also contains no heroes. There are, instead, many different protagonists with equal importance to the plot. This is a very difficult way to tell a story, fictional or otherwise. While, in reality, most meaningful social change is the result of collective action, we aren’t very good at recounting such a diffusely distributed account…

The introduction of a singular hero, however, replicates a very specific and historical power relation. The pioneers and the saviors: likely male, likely white, almost certainly brimming with unearned confidence. The veneration of the hero reduces others into victims: those who must be rescued. ‘The prototypical savior is a person who has been raised in privilege and taught implicitly or explicitly (or both) that they possess the answers and skills needed to rescue others,’ writes Jordan Flaherty in his book No More Heroes. To be a hero is fundamentally privileged, and any act of heroism reinforces that privilege…The carrier bag gatherer, meanwhile, is no lone genius (genius being its own kind of heroism, after all), but rather someone rooted in a shared existence.”

Homeless? How About A School Bus?: In Ashland OR they’re converting old school buses into very comfortable, affordable, portable homes. Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link.

What Birds Can Teach Us: Ellen Ketterson’s lovely and thoughtful lecture on Juncos has lots to teach us about how we (all creatures) evolve in place, and interact with “strangers”.

POLITICS & ECONOMICS AS USUAL

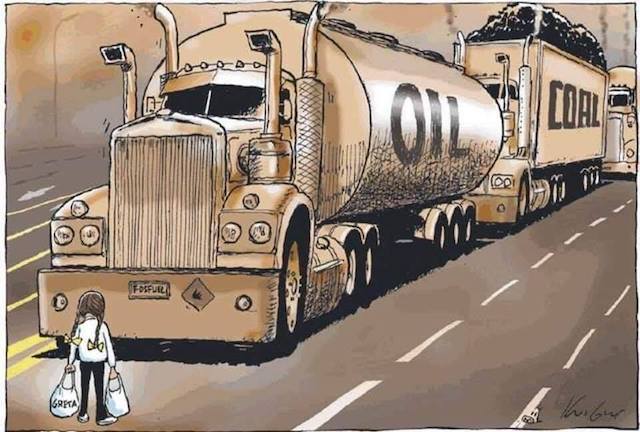

cartoon on Facebook, cartoonist’s name uncited; KriGur? Anyone know?

The Sad Truth About the Addiction Industry: Two new harrowing works depict the life and struggle of those living with chronic pain, and of those addicted to hard drugs. Amy Long’s memoir Codependence explains how, for the millions of patients suffering from chronic pain, life is lived in harrowing fear that anti-drug zealots will curtail their access to medications they simply can’t live without. “In 2016, the CDC changed its opioid-prescribing guidelines in a way that has really hurt pain patients, and I’m afraid I’ll never get the level of pain relief I need in order to write another book. So, it is a fear I live with daily but not in the way most people would expect.” And in this week’s New Yorker, Colton Wooten explains how the down-and-out are being collaboratively abused and destroyed by drug dealers and greedy “12-step” rehab/relapse centres and “sober homes” that exploit the availability of funds under the Affordable Care Act to keep addicts addicted. The addiction industry, groomed by its founders, the tobacco and alcohol industries, is much more robust and destructive than just drugs, pills, smokes and drinks. It includes our whole industrial food and pharmaceutical industry, where the profits to be made from addicting people to sugar, salt, fat and other ingested substances are dwarfed by the shared community costs of death, disease and chronic illness. Where there is more money to be made creating a few designer drugs for billionaires than drugs to cure the epidemics of the poor, and more to be made selling ineffective lifelong treatments for illnesses than selling a one-time cure. And the addiction industry includes our entertainment (including porn) and “information” and fashion industries, hooking us on the latest gadget or video and the rush of the latest “viral” meme. When you have an economic model that puts profit above everything else, the addiction industry flourishes.

The Industrial Food Industry Digs In: One of the fronts of the addiction industry vs the citizenry is the “official” dietary standards promulgated by national health departments. In past years, the deliberations for these have been dominated by self-interested industrial food corporations, to ensure the “food guidelines” continue to encourage consumption of the toxic and addictive foods that eventually sicken and kill most of us living in affluent nations. In the US, it looks as if this will continue indefinitely: The USDA and Health Dept have jointly announced that any changes will not consider any adverse health effects of “ultraprocessed foods, sodium, or meat”, despite mounds of scientific evidence just as compelling as that implicating the tobacco industry. In Canada, the industrial food industry was outraged at not being invited to create and co-write the latest standards, and Canada’s ultra-Conservative leader said that if he was elected (he wasn’t) he would scrap the new guidelines and invite the industry back for a rewrite. Money talks; download and save a copy of the new guidelines while you can.

The Dark Side of Techno-Utopianism: We so love new technologies, and the hopes and dream they might possibly fulfil. But we turn a blind eye to their dangers — exploitation, corruption, tyranny, abuse, hucksterism, propaganda, and misappropriation. Neither Gutenberg nor Zuckerberg ever understood what they’d unleashed.

Another Bank Bailout Needed Please: Uh, it’s the Repo Market this time. Um, it’s seized up, rates are bouncing all over the place. We need about, uh, $400B to get it moving again. Thanks! Thanks to Nicole Foss for the link.

45 Reacts to Greta, and Vice Versa: If you haven’t seen this short clip, take a look. No words need be said.

The Opposite of Democracy: The corrupt autocracy/plutocracy of the Russian state is evidence that democracy does not naturally follow the demise of an unpopular dictatorship. But its effects are not limited to the Russian borders. Those living in the annexed provinces of Ukraine or Georgia, or under the Russian puppet regime in Chechnya cannot even see the hope of freedom from fear and repression, even if they move to more democratic nations. Count your blessings.

NYT Paywall Corner: Behind the NYT paywall (which I can now only see with the help of news readers, to the extent I still bother to read their stuff at all), there are some strange things happening. Apologies if these links don’t work for you; if they don’t you’ll have to take my word for it. The NYT seems to be not-so-subtly endorsing Biden and subtly (using selected op-ed writers and pushing their stuff up the masthead) dissing Elizabeth Warren. Their rationale seems to be that Elizabeth is too “radical” to beat 45. So a recent article suggested that Facebook will prevent her from ever being elected. And an editorial by “opinion columnist” Bret Stephens, which appeared right at the top of the NYT’s RSS feed Friday, was headlined “Elizabeth Warren is Trying to Lose Your Vote“, and was nothing short of a character assassination, accusing her of being a radical “socialist” who would bring in an army of “mandarins” to implement her “unrealistic”, “risky” and “unsafe” plans. Stephens lauded fracking as a huge success and boon to the US economy, said that Medicare for All would mean huge increases in taxes for the middle class and put a half million administrators out of work, and said that the breakup of the mega-tech companies threatened an essential $500B, 800,000-employee industry. By pushing this ultra-right-wing, climate crisis-denying, negative, fear-mongering editorialist’s view, what does the NYT think it’s doing? And where did this wingnut get the credentials to warrant his “opinion” being published in the ostensibly progressive NYT anyway? [Meanwhile, in less visible, fairer coverage in this troubled publication, Robert Scott lauds Elizabeth’s plan to devalue the US dollar by up to 27% to create new domestic jobs as a “shock” fix to chronic underemployment, cheap imports and lost American manufacturing jobs. And another op-ed from last June talks at length about her sensible but radical policies to reduce income inequality, corporate power and corruption.] There; now you don’t have to read the NYT.

FUN & INSPIRATION

via Eric Lilius; several versions of this going around over the past 5 years; not sure who originated it

Improvvisazione Per Eccellenza: The annual international classical music festival MiTo (Milano/Torino) draws some of the best artists from all over the world. Sometimes, some amazing improvisational work just happens, as in this performance by Coro il Polifonico Adiemus of Rachmaninoff’s Vesper Bogoroditse Devo, or this one of Eric Whitacre’s Sleep. (The stunning 2,000 virtual voice version of Sleep is here.)

Speaking of Excellent Choirs: South Africa’s Stellenbosch University Choir is breathtaking in their energy, skill and variety of undertakings, from the local IsiXhosa song Indodana (“I Am The Voice”) to the soaring Jake Runestad work Let My Love Be Heard that even has some of the performers in tears. Bravo/brava, singers, Jake, and maestro André van der Merwe. (And one more extraordinary choral work: Octet VOCES8 performs a choral version of Elgar’s Nimrod Enigma Variation.)

Girls in Space: Award-winning animation One Small Step.

Anti-Vaxxers Beware: In a priceless take-off on medical warnings, “Doctors warn this year’s flu vaccine may contain high levels of immunity“. The Beaverton is Canada’s answer to the Onion.

My Ireland: Then-eighteen-year-old Sibéal Ní Chasaide sings Mise Éire, My Ireland, on the centenary of the country’s War of Independence. As Brexit again threatens Irish peace, this song now comes across as disquieting rather than cathartic.

Peter Gabriel and Youssou N’Dour: The dynamic duo team up on Peter’s In Your Eyes, also with Angelique Kidjo and the Soweto Gospel Choir at a benefit for Nelson Mandela back in 2010.

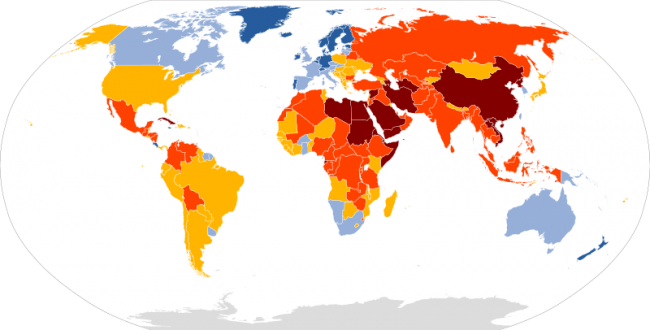

Even More Music: The World Listening Post has a carefully-curated collection of audio and video samples of modern folk music from over 100 countries.

Joy Williams, Anyone?: Readers tend to either love or loathe Joy Williams’ work, which is quirky, ambiguous (though not meanly so), and sometimes Kafkaesque. I love her stuff. Here’s a sampler of her most recent New Yorker stories, with the latest, The Fellow, IMO especially intriguing.

Extinction, Anyone?: Jonathan Pie cheers on XR and lampoons those who object to its “inconvenience”.

Feline Cystitis Explained, Hilariously: A Hungarian vet-cartoonist explains this common and uncomfortable cat disease. Ouch! Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link, and the one that follows.

Fungi Twice As Old As Previously Thought: A new discovery of fossils of one billion-year-old fungi requires the re-dating of the entire evolutionary path of life on Earth.

THOUGHTS OF THE MONTH

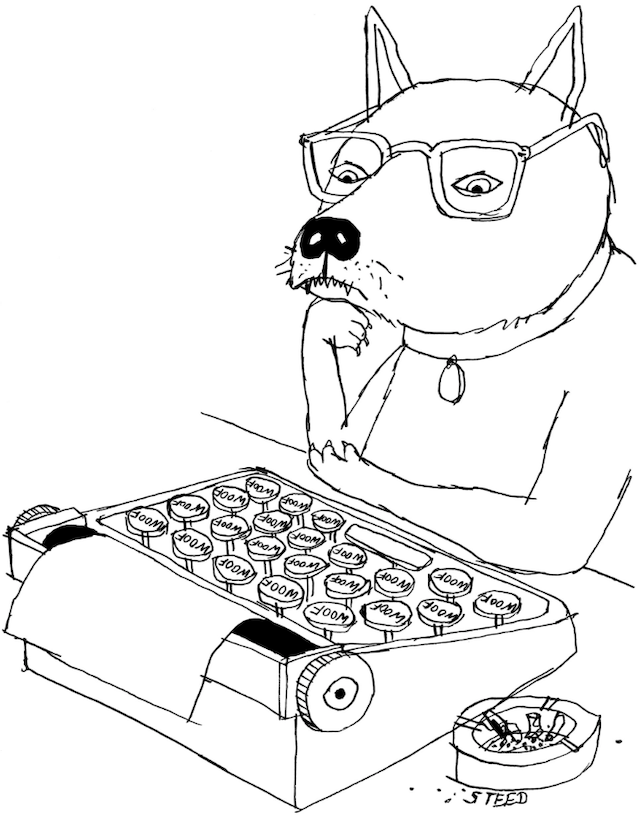

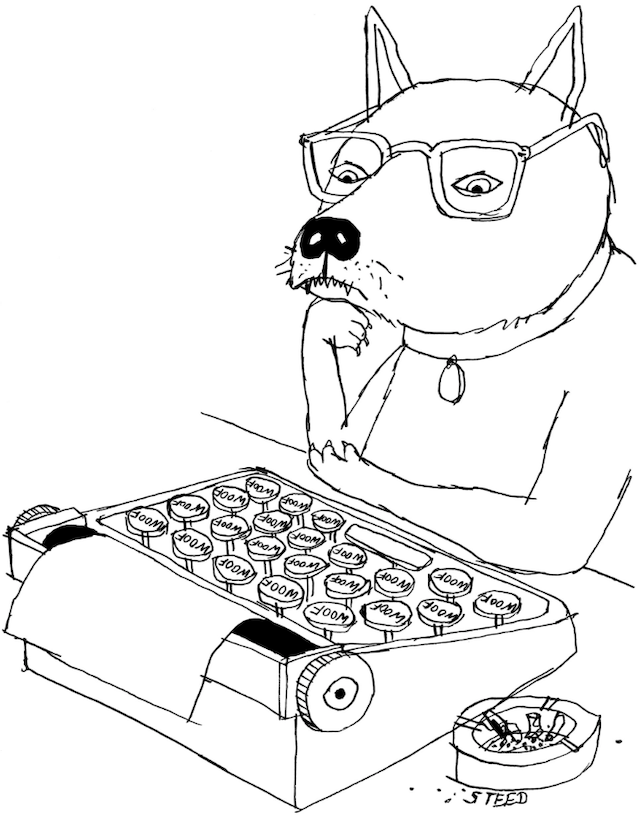

cartoon by Edward Steed in the New Yorker

Things I’ve Found Strangely Reassuring, by PS Pirro:

I recently finished Tim Flannery’s Europe, A Natural History. Millions of years of shifting continents, changing climates, giant creatures that came and went. Not to absolve us humans of our tendency toward wreckage, but it’s pretty clear the planet doesn’t need us to save her. Polar bears, redwoods, songbirds, they’re at our mercy. But the planet? She’ll sneeze and there we’ll go.

Edra Ziesk, on friendship:

I think some of my early – and longest – friendships were modeled on the relationship I had with my mother. Who was jealous, unkind, and angry. Who wished me healthy, but not really well: not more successful, more creative, happier than she perceived herself to be. I’m a loyal person and friendship, to me, is a permanent state, so I stayed friends with people who, as it turned out, at bottom didn’t really like me. Or who, like my mother, wished me healthy, wished me okay, but not well.

The one thing a friendship requires, always and only, is that the friends wish each other well. How that’s demonstrated matters less than that each friend knows they can rely on the good will and ear and heart of the other.

Tom Blakeney, in response to this Jonathan Pie video:

In one corner: hypersensitive immaturity. In the other corner: malevolent bigots. In the middle of the ring: the majority, who can not only take a joke, but can differentiate between humour and hate speech.

From Peter Kaminski, 5 recent tweets about Greta Thunberg:

William Gibson, @GreatDismal –

[responding to a tweet with “more flies with honey than with vinegar”]

No flies on Greta. Her autism, her lack of “honey”, is the result of a clinical inability to bullshit. Hence we, neurotypicals, hear a human voice of oracular clarity. Which terrifies and/or enrages some of us.

Zoe Rose, @z_rose –

I know it’s a side point, but it’s reasonable to predict that hundreds of thousands of previously unidentified autistic girls and women will recognise themselves in @GretaThunberg and realise what makes them different, and the very idea of that mass liberation makes me cry.

Margo Claire, @margowithan_o –

I am EXTREMELY inspired by Greta Thunberg’s refusal to smile or make jokes throughout all this media coverage. To see a woman so young not give up any of her power to ease the tension in the room is wildly thrilling and significant. I hope it’s contagious.

Dr. Ann Olivarius, @AnnOlivarius –

So rare to see a girl (not to mention a woman) so utterly devoid of any desire to please, placate or cajole. Greta Thunberg is effortlessly giving a master class in female anger. We should all take notes.

Greta Thunberg, @GretaThunberg –

When haters go after your looks and differences, it means they have nowhere left to go. And then you know you’re winning!

I have Aspergers and that means I’m sometimes a bit different from the norm. And – given the right circumstances – being different is a superpower. #aspiepower

From Kevin Armentrout:

While waiting to board our plane, my daughter was being her usual inquisitive self wanting to meet and say “hi” to everyone she could, until she walked up on this man. He reached out and asked if she wanted to sit with him. He pulled out his tablet and showed her how to draw with it, they watched cartoons together, and she offered him snacks. This wasn’t a short little exchange, this was 45 minutes. Watching them in that moment, I couldn’t help but think, different genders, different races, different generations, and the best of friends. In a country that is continuously fed that it’s so deeply divided, this is the world I want for her. Joseph, thank you for showing my daughter what kindness and compassion looks like. Continue to shine your light in the world.

While waiting to board our plane, my daughter was being her usual inquisitive self wanting to meet and say “hi” to everyone she could, until she walked up on this man. He reached out and asked if she wanted to sit with him. He pulled out his tablet and showed her how to draw with it, they watched cartoons together, and she offered him snacks. This wasn’t a short little exchange, this was 45 minutes. Watching them in that moment, I couldn’t help but think, different genders, different races, different generations, and the best of friends. In a country that is continuously fed that it’s so deeply divided, this is the world I want for her. Joseph, thank you for showing my daughter what kindness and compassion looks like. Continue to shine your light in the world.

Seal Lullaby, by Rudyard Kipling, also wonderfully, heart-breakingly set to music by Eric Whitacre:

Oh, hush thee, my baby, the night is behind us

And black are the waters that sparkled so green

The moon, o’er the combers, looks downward to find us

At rest in the hollows that rustle between

Where billow meets billow, then soft be thy pillow

Oh weary wee flipperling, curl at thy ease

The storm shall not wake thee, nor shark overtake thee

Asleep in the arms of the slow swinging seas

While waiting to board our plane, my daughter was being her usual inquisitive self wanting to meet and say “hi” to everyone she could, until she walked up on this man. He reached out and asked if she wanted to sit with him. He pulled out his tablet and showed her how to draw with it, they watched cartoons together, and she offered him snacks. This wasn’t a short little exchange, this was 45 minut

While waiting to board our plane, my daughter was being her usual inquisitive self wanting to meet and say “hi” to everyone she could, until she walked up on this man. He reached out and asked if she wanted to sit with him. He pulled out his tablet and showed her how to draw with it, they watched cartoons together, and she offered him snacks. This wasn’t a short little exchange, this was 45 minut