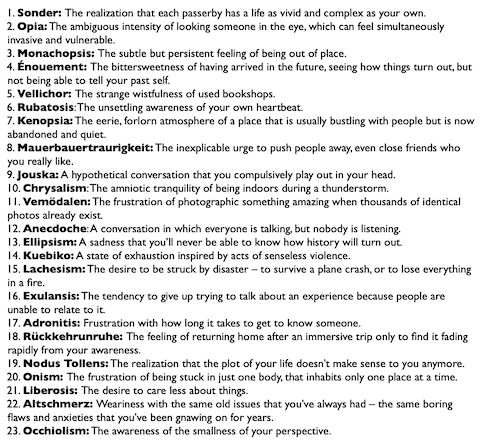

This post is a bit of a ramble, but I think there are some important ideas in it.

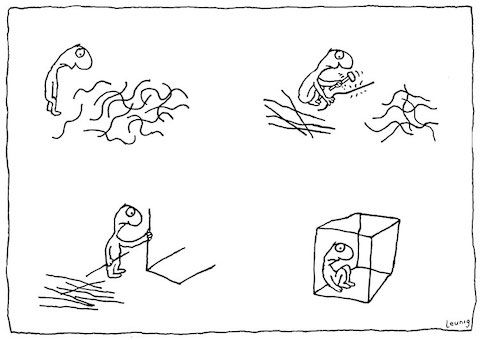

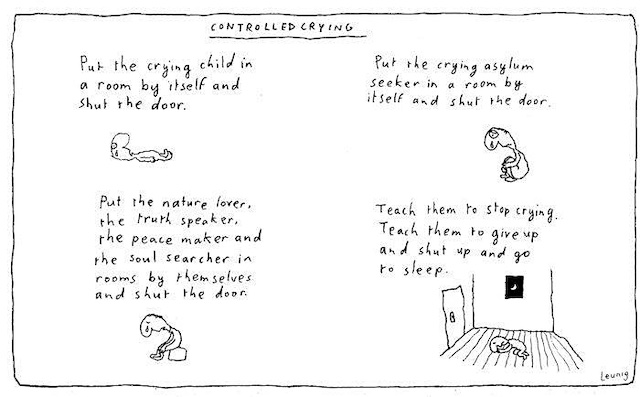

The prison of the self: cartoon by Michael Leunig

Some funny/strange things happened when I ceased to believe in the existence of free will:

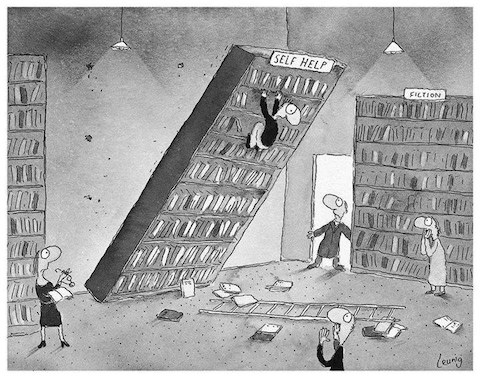

- I stopped reading books that, after excellent diagnoses of the sorry state of the world and of human culture and human health in particular, concluded with lame, simplistic prescriptions, many along the lines of “We all have to …”, or “The first thing you need to do is …”

- I began to see the ludicrousness of our incarceration systems, predicated on the morally and philosophically bankrupt idea that punishment is an appropriate and effective way to deal with anti-social behaviour. I also understand why, despite this, there are more people incarcerated than ever before in history.

- Likewise, I began to see “twelve step” programs, CBT, “reprogramming”, diet regimes, and similar programs to change human behaviour as cruel and misguided. And I understood why they were created, and why they are so popular, and why, despite the overwhelming evidence they don’t work, they haven’t been supplanted by something that does work.

- I appreciated at last why I have always found most self-help and self-improvement books loathsome and patronizing. And I understood why they are so popular, and why so many well-intentioned people are driven to write them.

- I stopped blaming people for their beliefs and actions, no matter how outrageous and dangerous I found them, and stopped using the words “evil” and “insane” and their equivalents, to describe people and their actions. And I understood our propensity to assign blame, to ourselves and to others.

- I stopped believing in nonsense homilies like “You can accomplish anything you set out to do if you believe and work hard enough at it”. And I understood why so many believe so desperately that these homilies are true, must be true.

- I stopped believing in meritocracies (including reward systems in schools and workplaces). And I understood why almost all educational institutions and workplace hierarchies are based on them, and why they are so little challenged.

- I stopped using judgemental, absolutist terms like good and bad, fairness and justice, because they presume we have the free will to behave in any other way than the way we do, when we do not. I know that’s a sacrilege, a culturally offensive statement. Acknowledging this truth did not come easily to me. And I understand why my saying so rubs so many people the wrong way.

I’ve written about this a lot, but would again recommend The Secret History of Kindness by Melissa Holbrook Pierson if you are open to the possibility that we have no free will whatsoever.

Just to be clear, I am not a determinist. I don’t think everything in life is foreordained or predictable — there are a million variables that change the situation we face, every instant, and they have an enormous impact on what we think and do. My argument, based on the preponderance of evidence I have witnessed, read about, and studied, is that, given those ever-changing circumstances, how we react to them is strictly a result of our biological and cultural conditioning and not the result of any exercise of self-control, independent rational thought, choice or free will.

I have no time for the fake ‘non-dualists’, gurus, and spiritual ‘leaders’ who, to avoid alienating their large and lucrative flocks of faithful readers and followers, claim that there is a road to happiness, liberation, enlightenment, oneness, fulfillment, or awakening — a claim that seems to say that, while we are all ‘one’, we still have “kind of” free will that allows us, if we are made of the right stuff, individually to resist ‘bad’ actions and successfully and consciously pursue ‘good’ actions. You can’t have it both ways, folks. You either have free will, or you don’t.

Melissa’s book provides lots of evidence that we don’t, and, now that my blinkers are off, I see the evidence all around me.

But in this article I’m not trying to convince anyone — instead I’m trying to articulate the implications if you believe we lack free will.

I am always astonished at the things that now trigger rage, or outrage, or fear, in me. They don’t make sense, but still the anger and terror are there — in my reaction to careless drivers, to badly-designed systems, tools and processes, to cruel behaviours that belittle, oppress, and terrify others. I know the perpetrators can’t do other than what they do. I know they are acting out their trauma, or doing their best, incompetently. The anger and terror diminish much more quickly, now, than they once would have, but they still arise, making a fool of ‘me’, in retrospect.

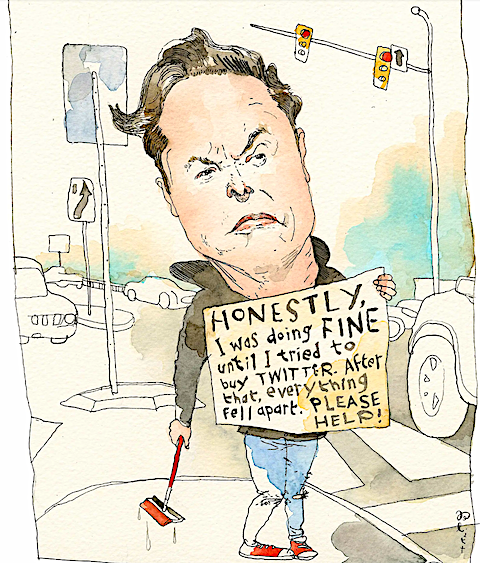

Gabor Maté has a new book out, one destined to be a best-seller, since, not only does it rehash his brilliant condemnation of the way we fail to prevent and account for childhood trauma and disconnection in the ubiquitous modern malaise that I’ve dubbed Civilization Disease, but it also includes a new self-diminishing (we all love that stuff) story about his own humbling “spiritual awakening”.

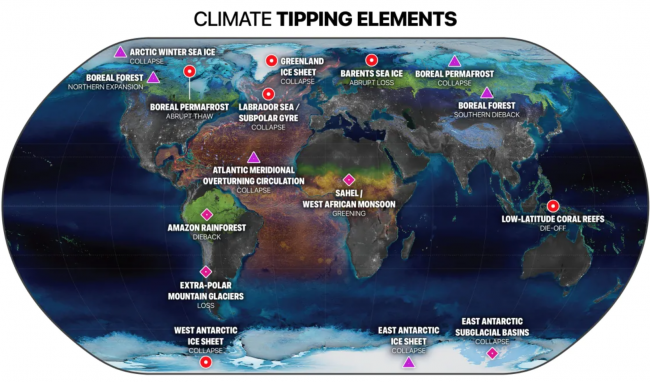

Sadly, though, it ultimately deals in hope and redemption, those shoddy products of the tricksters in politics, business and religion that never turn out well. It prescribes both personal and societal solutions for the Disease that would be great, if they were possible, but which, like the magical-thinking global human consciousness-raising that some predict will save our species and planet from collapse, are no more possible than the Second Coming. Still, we want to believe. And, especially, we want to believe in our personal and collective free will to make the world better, to make it other than the only way it could have been and can be.

One of the things I like about the Japanese concept of ikigai, which encourages us to reflect on and map “what makes our life worthwhile”, is that it doesn’t prescribe ways to change who we are, to make our lives somehow ‘more’ worthwhile. It accepts that we are who we are, and focuses on self-awareness of ‘who’ that is, rather than the grim hopefulness of ‘self-improvement’. Indeed, some writers on the subject fully accept that we have no free will: The last chapter of Ken Mogi’s book is entitled Accept yourself for who you really are.

Though, of course, whether we can or do accept ourselves, or even care to try to discover who we “really are”, is not something in our control.

Another concept in ikigai philosophy that I’ve learned about more recently, is the idea that an entire community can have a collective ikigai. I wrote recently about how our communities are so fractured and incoherent, and my guess is that it would therefore be fruitless trying to suss out “what makes our community worthwhile to ourselves and to the more-than-human world of which we’re apart?”. This implies a humble sense of service to our community and the world that seems lost in the current cacophony of collapse.

Until collapse drives us to regain our sense of community, I think we’re going to have a harder time of it because we cannot answer that essential question, which is one not of identity, with which we’re so preoccupied these days, but, rather, of purpose.

There is a short story, or maybe a novella or play, brewing inside me these days about a (hero-less) group of people looking to build community after collapse. A key question for them must be their collective, emergent ikigai. I suspect that, unless its characters acknowledge their lack of free will, and appreciate their ‘a-part-ness’ and connection with the larger community of Earth, and discover their collective purpose as part of that greater whole, they will be humanity’s last tiny echo on the planet, rather than its reintegration into a damaged, healing planet.

Of course, they won’t have any choice in how that turns out.

S

S

Y

Y