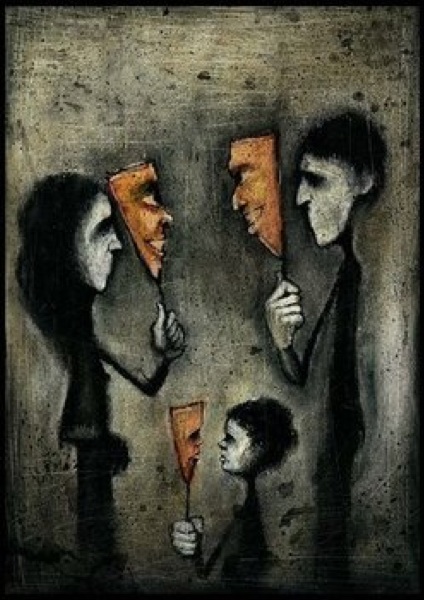

comic by Reza Farazmand

You don’t have to look far to see discouraging signs of the left’s demise:

- The total capitulation of the handful of real leftists in US government to the Biden administration’s xenophobia, war-mongering, and total inaction on income/wealth inequality and climate collapse.

- The hard-right shift of so-called “Labour” and “Liberal” parties everywhere in the world.

- The massive infighting that is destroying and neutralizing many progressive organizations.

- The splits and defections among leftists by bitterly-opposed factions.

- The success of neofascist parties and governments from the US south to eastern Europe to India and beyond.

- And the complete incapacity of the few remaining progressive governments to enact progressive policies and programs (such as UBI) despite their mandate to do so, and despite the fact such programs are overwhelmingly supported by citizens.

Until now I have avoided trying to diagnose this, because in politics things change fast and it’s easy to see patterns where none really exists.

But now it’s pretty hard to ignore. What is behind this collapse, this implosion of the left when progressive action is now most needed? What’s been going on when we weren’t paying attention?

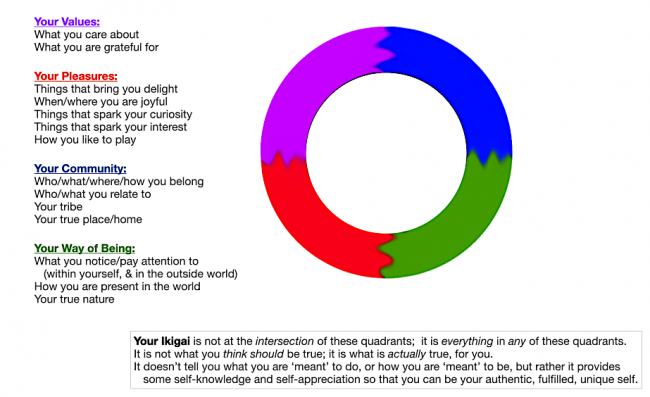

Probably as good a place as any to start is with George Lakoff’s classic Moral Politics. George told us twenty years ago that the right told a better story than the left, and as such has ended up framing all discussions using its own terms of reference and vocabulary.

I think this has only worsened since then. I’d go so far as to say that the right is now the only political force telling a coherent story at all. The left’s story is ambivalent, abstract, unactionable, oppositional rather than proactive, and full of “yes buts”.

The right’s story might be simplified to the following:

- Governments and regulations are necessarily bad, evil, and objectionable by virtue of their inherent incompetence, bureaucracy and propensity for overreach, opacity and corruption, and they therefore need to be dismantled. (The right can call on a ton of one-sided but pretty indisputable evidence for this jaded argument.)

- Things are worse than they “used to be” because of a moral-spiritual vacuum that has muddied what was once clearly seen to be the line between good and bad, right and wrong. Terrorism, addiction, crime, and the anxiety and acedia of many citizens demonstrates this. Humans are naturally weak or sinful and need authority figures (police, military service, religions, strict parents and laws — but not politicians or regulators) to keep them on the right path and reverse the “moral decay” we are seeing.

- A strong work ethic is essential to a good, meaningful life. Progressive governments have offshored and outsourced work, allowed in too many immigrants who compete for jobs and who don’t share our “values”, and have passed laws that allow too many to live without even trying to find “real work”. That needs to be reversed.

I don’t know of many people who don’t have at least a little sympathy for these arguments.

George Lakoff argued that the left needed to construct (or repair) a coherent alternative story about the value of nurturing our children and each other, teaching and learning to think critical and independently, and the importance of government and regulation to support citizens who, for reasons beyond their control, cannot obtain the essentials of a healthy life without such support.

Because it’s hard to figure out how to make it work, this is a far less compelling story to most people, and, as success stories of its use fade further from public memory, it sounds more and more like idealistic hooey rather than a framework for social self-management and governance. Each element of it is open to attack by conservatives using their own frames of reference, which have now become the de facto frames of reference in most of the world.

Now I’m going to sound like an old fogey, which I suppose I am, because I think what has facilitated this implosion of leftist effort and energy is the serious decline in our systems of education (formal and informal) over the past forty years. This is not anyone’s fault — it was the inevitable result of several things:

- The inability and unwillingness of governments to properly fund, facilitate and monitor educational systems that can produce a basic level of language fluency, cognitive capacity, and literacy (breadth and depth of study) in every young person.

- Commensurately, a propensity of education systems, right up to ivy league universities, to award unwarranted passing grades and top marks, to pass the systems’ growing dysfunction and incapacity to provide education basics on to the next level of schooling.

- The enormous increase in the complexity of our society, which of necessity has made education shallower and spread across a wider range of disciplines.

- The decline in the quality and quantity of discourse, starting in families, about the state of the world. This is substantially the result of the necessity, due to complex changes in economic dynamics, for parents to both work, and to work two or three jobs each, reducing the communications that children have in their early years with (hopefully) more articulate and informed adults.

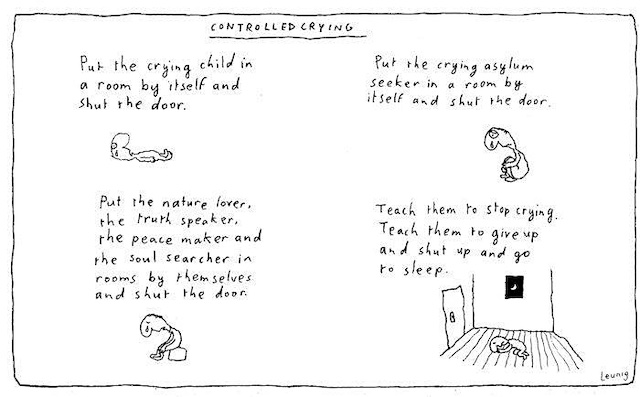

If young people aren’t given the tools for basic cognitive development and intellectual exercise, we shouldn’t be surprised when they are just overwhelmed by what’s happening, and cleave to simplistic narratives and an over-reliance on “what my friends say” in forming their own beliefs and values. If you never wean your child off pablum, how can you expect them to digest solid foods?

I would argue that we have, with the best of intentions, pretty much cast young people adrift at an early age to try to make sense of the world among their equally clueless peers. And while I am aware of the “helicopter parent” phenomenon, my observations have been that the interventions of such parents are more about the parents’ egos (“Why did my brilliant child get such a poor grade in your class?”) and about grades, than they are about the education of children.

I have been reading Carlo Rovelli’s book Helgoland, about the development of quantum science, and what struck me most in reading it was that the bright lights in science in the last century had a staggeringly broad and deep understanding of disciplines spanning not only many sciences, but also politics, the arts, philosophy and literature, and they drew on all these disciplines and their reading and studies, in making the momentous advances achieved in their fields. I think our modern education and work-world systems are so hollowed-out and specialized that they preclude the chances of this happening now, and I think the documented sharp decline in innovation over the past forty years, exactly when we need more of it, is evidence of that.

So we end up with people who go to work for progressive organizations getting immediately embroiled in how those organizations are themselves suboptimal in terms of the ideals they aspire to, and not understanding the context for or the importance of subordinating those concerns to the objective of achieving the organization’s vital goals, whether those goals be climate action, institutional reform, or regulating corporatist excesses.

They can’t be blamed for wanting to put their own organization’s house in order before trying to change the world. And they also can’t be blamed for their ignorance, naïveté or cynicism about whether changing the world is even possible: “This system has never worked for me; why should I work to reform it?”. If they had as background an understanding of the history of what the organization has accomplished, and of the urgency of what it needs to accomplish now, they would perhaps be willing to set aside their (mostly legitimate) concerns in non-urgent areas they do feel they have come say and control over, to focus on urgent actions that they most likely feel are hopeless no matter what they do.

Without that historical background and understanding, and the cognitive capacities to understand its implications, it’s not surprising that they bring a certain self-centred nihilism to the work they do, and a certain us-vs-the-world-including-progressive-organizations attitude to the workplace.

The result is that, as this exhaustive study has found, many, many progressive organizations have been paralyzed or even destroyed by idealistic internal disputes, infighting and distraction from their mission. That has left the right, including the courts that are now in many places stacked with the extremist appointees of neofascist governments, free to further undermine and dismantle restrictions on those governments’ power, and to perpetuate that power in overtly anti-democratic ways. A recent international study found that more than half of the young people surveyed didn’t think it was important that the government of the country they lived and worked in was democratically elected. How can we expect them, with such ignorance of (and/or cynicism about) the importance of democracy, to work to defend it?

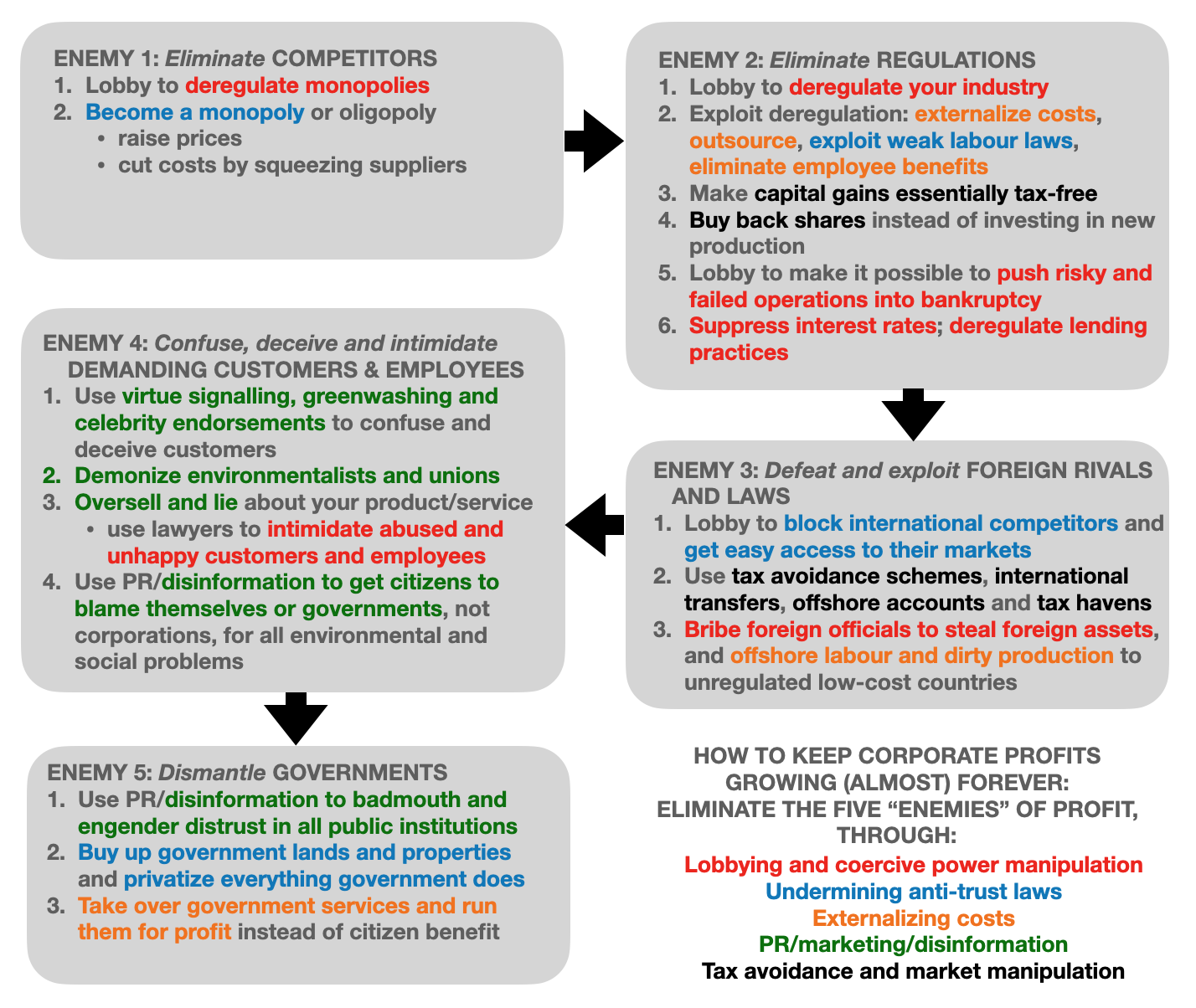

A recent newsletter from a progressive organization I have followed and encouraged for years, commenting on the ruling of a panel of right-wing judges that the decisions of American regulatory authorities (like the SEC, FTC, FDA, EPA etc) are, across-the-board, unconstitutional, actually said the organization found the ruling “a relief”, in that they could now get on with the work of creating replacements for these regulatory authorities that were more accountable. What planet are they living on? Their naïve assumption seems to be that if the ruling is upheld, they will be empowered to “build back better”. In reality, this ruling, if upheld, opens wide the door to massive levels of securities fraud, mega-pollution, toxins in our food and water, price-fixing and other monopolistic practices, and bribes, extortions and other illegal trade practices, with complete impunity for the corporations perpetrating them. Any corporate regulation will have to be subject to exhaustive court proceedings, which are almost invariably won by the side with the deepest pockets — the corporations.

But I suppose, if people haven’t studied history, and don’t understand how the world really works, such fanciful utopian “build back better” dreams will incline them to celebrate, rather than be enraged at, the egregious judicial malpractice of the type that led to this demented ruling.

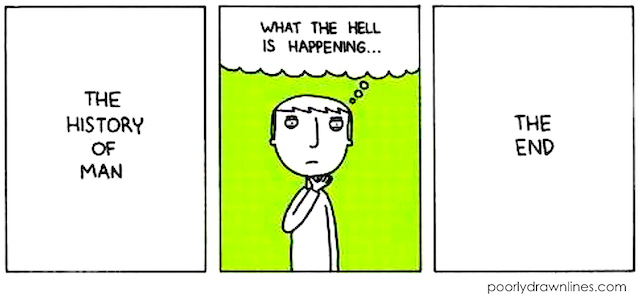

Max Planck famously said: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” The same is true of other beliefs and truths — each new generation will grow up, for better or worse, free of many of the beliefs and prejudices, as well as the historical knowledge. context, and learnings, of the ones that passed before. Unfortunately, that’s one of the reasons our species keeps repeating the same mistakes.

In the book The Fourth Turning, the authors foresee the current generation just starting to take over as being one that is somewhat insular, idealistic and fiercely loyal to its self-selected groups. They also warn about the current times, as a reviewer summarizes:

[The fourth turning] means America and the free world are due for a deepening crisis characterized by severe drops in financial markets, declining confidence in America’s institutions, and, very likely, “a sudden downward spiral, an implosion of societal trust” (p. 275). This deepening crisis should reach a climax at about the year 2020, when all of America’s problems will seem to have congealed into “one giant problem, the very survival of the society will feel at stake.”

The historical pattern is strong enough that we should take this scenario seriously. But we do not need to accept it as inevitable. We have choices, and we can choose to change the future. Even Strauss and Howe, on their WEB discussion group, state that “changes in how we think about events can determine the direction and outcome of the events themselves.” If consumer confidence is shattered, the government overreacts to the terrorist threat, and the public is seduced by maximalist solutions, then the Fourth Turning will be upon us.

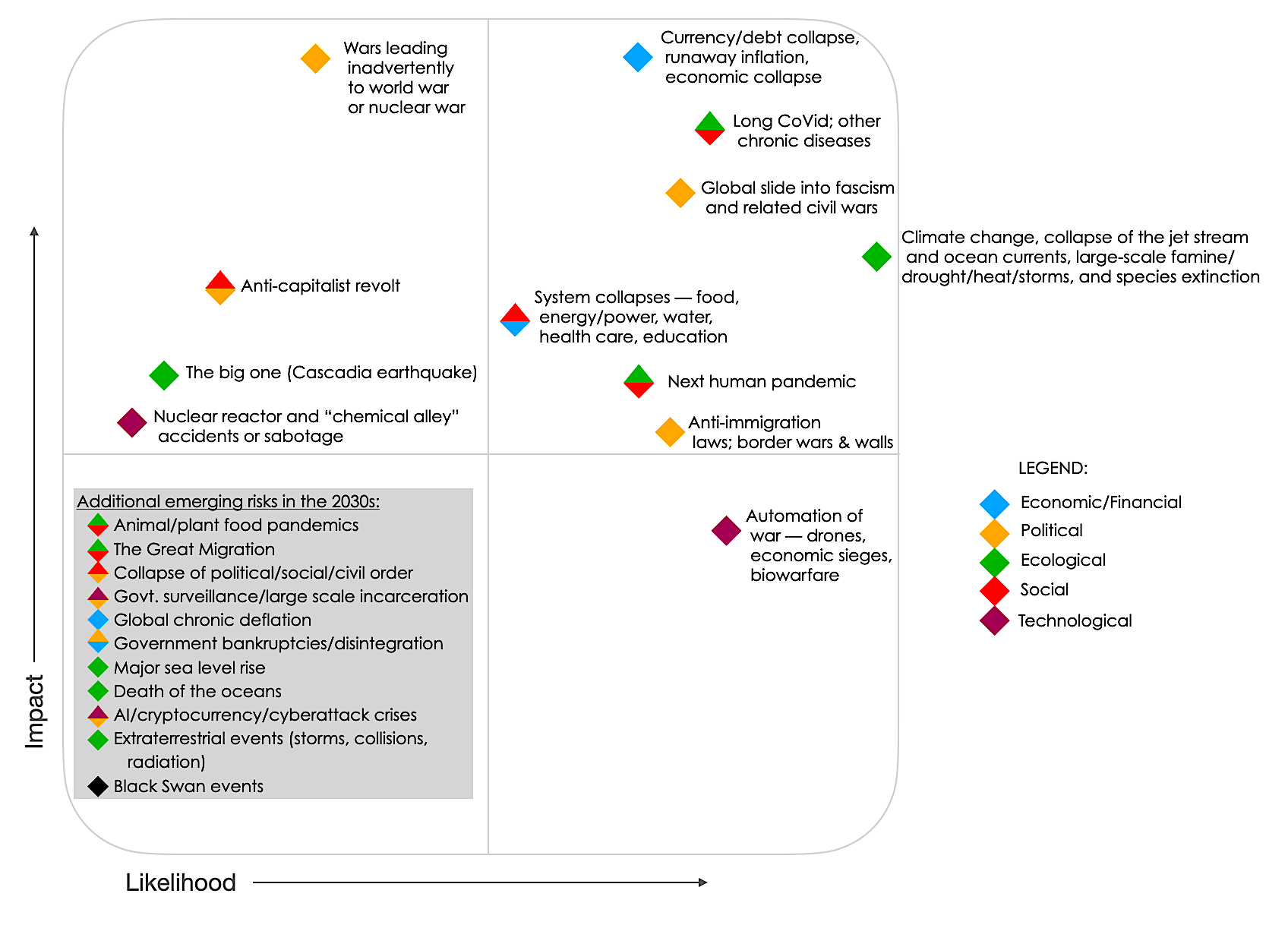

So, perhaps, here we are. Fourth Turnings are a time of upheaval and unrest — the last one ushered in two world wars and the Great Depression. To have this happening exactly when the left seems to be imploding, and is bereft of a coherent story to tell a world floundering with anxiety and despair about our future, is not auspicious.

In his latest article (and his upcoming book) Rhyd Wildermuth, who grew up as an anarchist and spent much of his youth working with the homeless and the addicted in Seattle, is less kind in his assessment of the left’s internal dissension and naïve idealism, which he says has led to the kind of colossal blunders that led to the recall of Chesa Boudin. That recall movement, while admittedly funded by right-wing billionaires, was, he says, most fiercely supported by BIPOC people and others living in poor, working-class neighbourhoods, who had to deal directly with the often-unnerving consequences of Chesa Boudin’s bold experiment, far more than did the idealistic insulated-by-wealth “Professional-Managerial Class” (mostly in tech jobs) who supported Chesa’s experiment.

Rhyd argues that the relative wealth and privilege of many young progressives has “blinded” them to the realities that their idealistic beliefs, when implemented (in progressive cities and organizations), impose on the lower castes and classes of citizens, leading to a left that is dysfunctional, disconnected, and alienating to the rest of the population. He goes so far as to say:

In the end these progressive policies are acts of class warfare against the poor. It’s the lower class who is dying from these overdoses, it’s the lower class (and especially the minority communities Woke Ideology claims to defend) who are harmed most by drug-related crime, and it’s the lower class who has begun revolting against the Professional-Managerial Class’s vision of ideally-managed societies.

Particularly in the United States, anarchist frameworks are hobbling any real leftist organizing towards class-based analysis of these problems. This is of course partially because the most prominent US anarchists are all part of the Professional-Managerial Class, but more significantly because their relentlessly juvenile perception of what is “authoritarian” means they oppose not just state efforts but also any collective effort to deal with crime.

So perhaps the problem that has caused the implosion of the left is that, as it has become increasingly disconnected from the working classes and the poor, it has forgotten, lost track of, and stopped fighting for, the citizens it once espoused as its allies, the core of its constituency. And in the process, it has played perfectly into the hands of conservative groups who are more than willing to pay lip service to the beliefs of the dumbed-down working classes, and to exploit their anger and recruit them with the simplistic three-part story I outlined above.

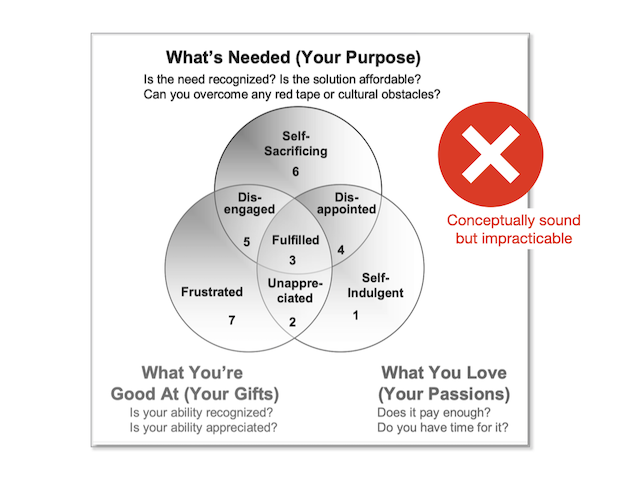

The climate crisis movement, and other once-inspiring leftist groups, have IMO let their critical goals and messages be diluted by what Rhyd calls Woke Ideology that insists that climate action, to prevent the collapse of our ecosphere, cannot proceed until and unless it incorporates “social justice”, including reparations for past injustices. What hope does any movement, already facing fierce opposition from conservatives and corporations, have if it is distracted by debates on historical justice, race and ideology, from its urgent need for direct action now — to damn well block, break and take over (occupy) corporate activities that are destroying our planet’s ecosystem. In a world ravaged by ecological and related economic collapse, no one is going to give a tinker’s damn about which groups were more or less disadvantaged by the corporatist misdeeds that gave rise to it. And only an extremely insulated, ignorant, sheltered, idealistic, ideology-obsessed cohort could believe otherwise.

How will this all play out? My guess is that this decade will see the further decline of the left as it sinks further into internal squabbling and dysfunctional irrelevance, and a mostly-unrestricted advance of neofascist governments just about everywhere. Private corporate interests and billionaire oligopolies will finish their looting of the public purse and public assets and, with the exception of its ‘moral section’ (law enforcement of the oppressed classes, security, and the military), the hollowing-out and slow drowning of central governments as providers of social and support services.

That will leave us totally fucked as economic and ecological collapse deepen and become global in the 2030s, since there will be nothing left in the treasury to fund the kinds of rescue operations that prevented the most catastrophic misery of the 1930s — rescue operations like the New Deals, with widely-accepted 90% taxes on corporate profits. When we reach that stage in the 2030s, the governments will, at the behest of their owners, the oligarchs, probably instead turn on the citizenry to try, unsuccessfully, to maintain order. It’s not going to be pretty, but we’ll survive it.

In the meantime, the left might actually wake up and act on behalf of the struggling 99%, and might once again become relevant. But talk about dangerous times: This won’t be a genteel slue to socialism. It could well be more like the times of the Russian revolution than anything most of us have ever conceived of (or read about). In terms of our propensity to gravitate towards radical collective action — a true rebellion, not the play-acting of XR and its ilk — there will be a strong pull, fed by generations brought up in the cult of me-first individuality, to dissolve into everyone-for-themselves atomized struggle instead. That’s what the oligarchs and their paid-for politicians are counting on.

They may be in for a surprise. And Generation Z might surprise us most of all. Especially that generation of young people outside of the countries of White Empire. Having lived lives of precarity, with social cohesion their strong suit, and little to lose, they might prove to be better revolutionaries, more prepared to risk everything for their cause, than the rest of us. Whether they’ll then be considered leftists is anyone’s guess. Their verses for The Times They Are a-Changin’ may be very different from ours. They may very well not be in English.

Still, we can be pretty sure that “The order is rapidly fadin'”. And the demise of the “old left” will lead to some new group, eventually. A group with a better first-hand knowledge of what it’s like to be poor, oppressed, and exploited, and an appreciation that ideology and idealism are not the tools of change.

This old fogey hopes to be around to cheer them on.