image from pexels, CC0

When a loved one is very self-destructive you can’t control their fate; at some point you’ve just got to let them make their mistakes and hope something in them wakes up before they wind up dead. That’s pretty much how you’ve got to be with the entire human species at this point. — Caitlin Johnstone

The crows’ antics have abated for now. It’s breeding season for them, and instead of endless play, swooping, chattering, and staging for the daily migration to the massive Still Creek roost, they’re building nests and staking out territories for raising their families. As they’ve largely vanished into the top central branches (the ‘crows’ nests’) of coniferous trees, the seagulls, which start nest-building next month, and the pigeons, which breed all year long, have taken over centre stage here.

I’m wandering along the side streets near the river. It’s raining, and the downpour reminds me of the Richard Shelton poem:

It Is Raining

and a line of light is just beginning

to open the lid of the horizon.

Somebody leans out an upstairs window

and shouts, “Thanks for the beer.

Write when you get work.” A car

coughs, starts, moves down the street

avoiding the deeper puddles

stippled with rain. It passes a dog

in a doorway, his tail curled

carefully around his delicate feet.

It is raining in Coblenz and in Buda

and in Pest. It is raining

on the top and bottom of the world.

It is raining in Argentina. The bank vaults

are leaking. The German certificates

of deposit are beginning to mold.

It is raining on the gleaming seats

of hundreds of parked bicycles.

It is raining for those who plan to go out

and for those who plan to stay in.

It is raining quietly, the rain of forever,

the rain of good-bye, the rain of tomorrow.

It is raining on horses who stand

on three feet in wet fields

and speak the language of every country.

It is raining on the mansion on the hill

with one small light from the kitchen

where the cook has a toothache and cannot sleep.

She sits playing solitaire, looking around

the empty room quickly, and cheating.

It is raining on the glistening tailings

from exhausted mines and on little

ghost towns in the mountains.

It is raining on the old house in the city

far away where we once lived another life.

It is raining wherever you are

and wherever I am and wherever

we are going and have been.

It is raining on the tombstones, on the flat

stones and the upright stones. It is raining

into the open graves that are waiting.

It is raining on history, on the battlefields

of long-lost wars

and the bronze statues of forgotten heroes.

It is raining on Alcatraz, in the fog,

where mushrooms are growing under steel bunks.

It is raining on millions of pale yellow

butterflies far out at sea, migrating

like angels from one world to another.

(from The Last Person to Hear Your Voice)

Here, it is raining on the river, on the leaves (new, and old, and just budding). It is raining on my rooftop weather station, whose monitor tells me it has rained 12mm so far today. I don’t know if it’s raining in Donetsk, or Mariupol, or on the billionaires’ mansions and factories, or on the offices of journalists faithfully reporting the truth as it’s fed to them from sources rewarded for the immensity of their lies.

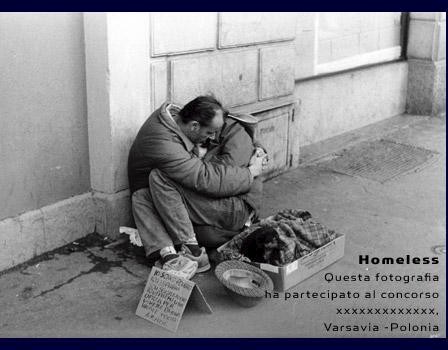

I don’t know if it’s raining on the homes of climate scientists, trying to figure out what they should tell their families, or on the homes of neuroscientists, still searching in vain for the self. I don’t know if it’s raining on the Pentagon, or the Kremlin, or the beggars in Sana’a and Kabul. I don’t know if it is raining on the laboratories of quantum physicists who confess, with puzzlement, that it appears there is no time for it to rain.

The goslings are starting to hatch, and to discover this strange and wondrous world. Their parents are wisely wary of me. Overhead, a merlin, small and fierce, soars.

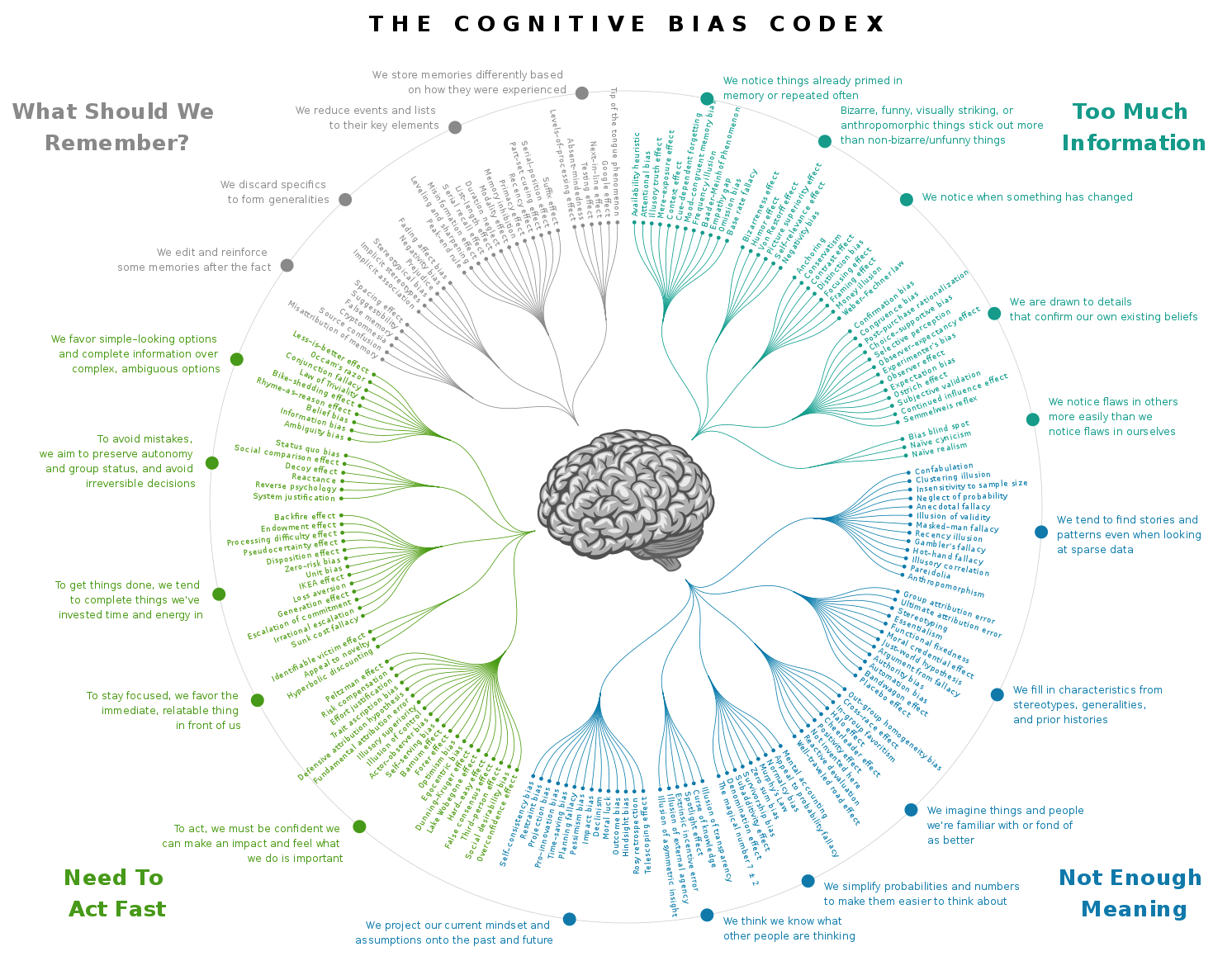

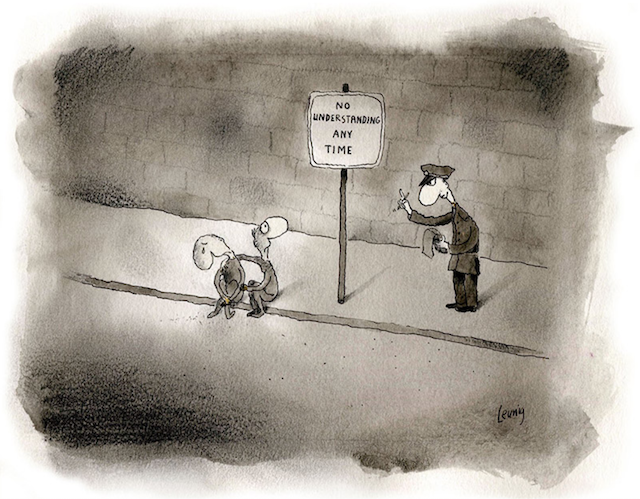

This is the story of my life: Every time I think I’ve got it figured out, finally made sense of the world, something comes along to blow that understanding to pieces. Complexity, collapse, human nature and our belief systems, how the world really works, radical non-duality: There is no end to the unlearning and relearning and the astonishing declarations of “How did I not see that before?”

We can, of course, never know the truth. We just peel back the layers, thinking we’re getting closer, and when we get to the centre it is empty. Everything just falls away. Like in The Prisoner where Number Six relentlessly seeks to discover who is Number One, only to discover he is face to face with himself.

We want to know so badly. And we desperately don’t want to know that what we thought was right was not, that it wasn’t even close. We will fight to the death to defend our version of the truth.

On the river trail, the dogs take their humans for walks, trying to show them the right way to do it. But the humans don’t seem to be paying attention.

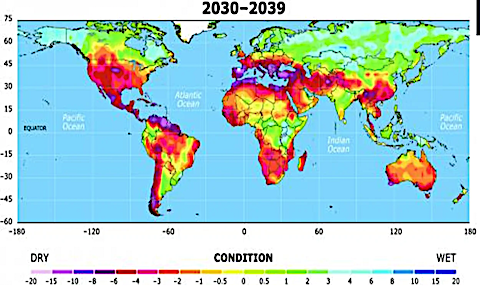

I think about our planet, slowly burning up. I think about all the species except one, and its food sources, that are being extinguished, one by one. And the oceans and lakes fouled, the fertile soil washed away, the air polluted, the forests razed, the rivers dammed. I imagine the accelerating sixth great extinction of life on earth playing out. The planet becoming a much simpler, stormier, more desolate place.

I think about Caitlin’s hope, expressed at the top of this post, and first I think I share it, and then I realize I do not. For a while, I wondered if my pessimism was just my way of shrugging off responsibility, inuring myself to the tragedy ahead. I don’t know.

This planet will still be beautiful, even if most of its surface is dead. Even if there are no “civilizations” left on it. Every story has to end, and there is no last-minute skewing of its plot to make this one’s end a heroic one. There need be no shame in that; we did our best. We can wish for a different ending all we want, and it won’t change anything. This one’s already in the can.

The cherry blossoms are out. A little late this year, but that’s OK. We’ll see them again, each year, in all their ostentatious profusion, for a while yet. And then we won’t.

And that’s OK too.