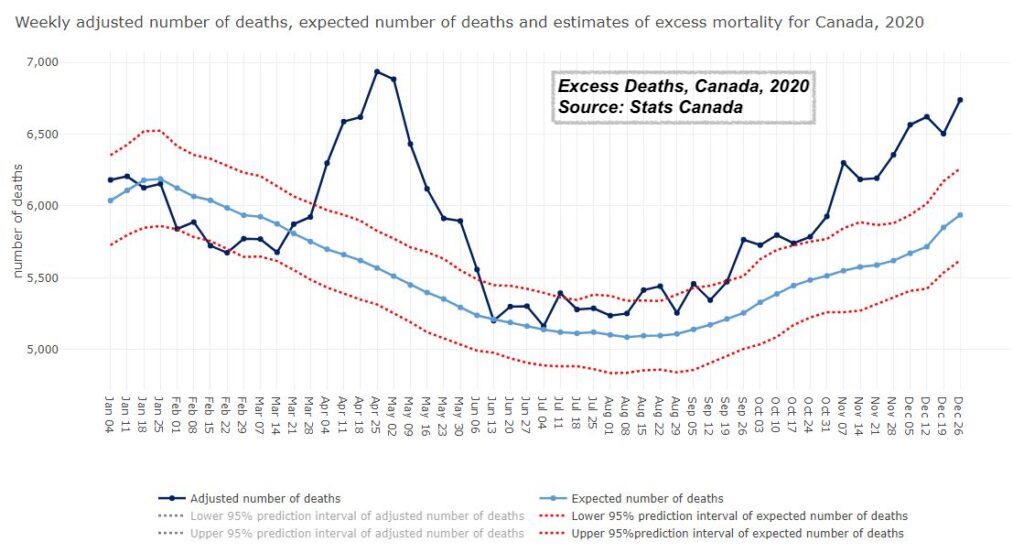

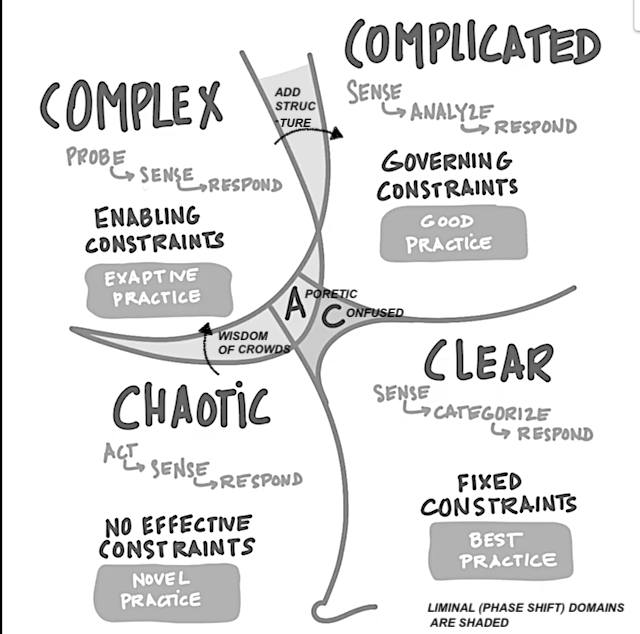

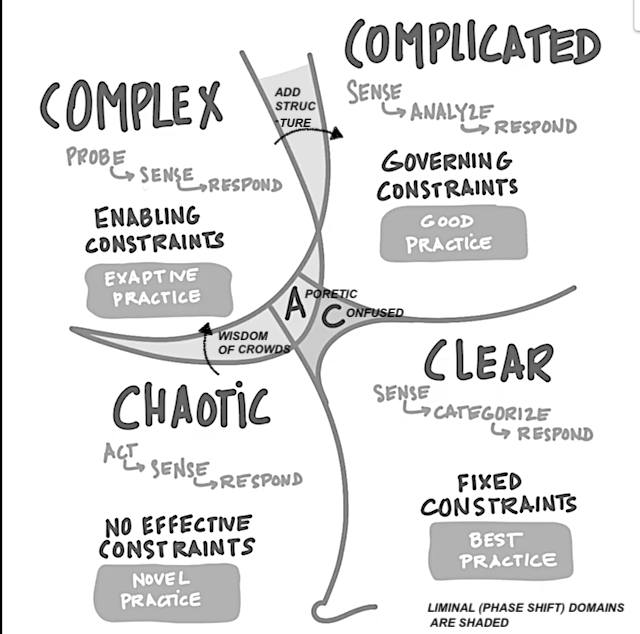

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework (2021). Adds liminal domains, points of uncertainty or paradox, notably the aporetic domain, from whence, notably, NZ’s Jacinda Ardern chose to cede decision-making authority to health experts as being better equipped than politicians to determine the most sensible next steps to deal with the pandemic, buying time in a period of crisis and keeping options open.

This morning I watched a fascinating conversation between my Welsh friend Dave Snowden, and filmmaker Nora Bateson, daughter of anthropologist Gregory Bateson and step-daughter of Margaret Mead. Nora is carrying on her father’s work on complexity. The subject was “When Meaning Loses Its Meaning”.

Here are my notes from the session; they’re not direct quotes:

If you want to change people don’t try to change the individual, because you can’t, and besides it’s arguably immoral to try; instead change who they interact with. Then they will make their own decisions about how they change and what they do as a result — and what you’re concerned with is what they do not what they think.

For a rich, “entangling” contextual connection to occur in a group of people, they don’t even have to talk together; what’s important is that they work together, do things together. Then they discover what they have in common, what they both care about, instead of what separates them, and that new contextual understanding can change what they do going forward, and hence change what they understand and believe. They end up with entangled narratives and contexts for sense-making, which then allow “intimate conversations” (trusting, lowered guard, more openness) to occur.

So you change their interactions, and who they interact with, rather than a ‘therapy’ approach of trying to change their ‘wrong’ beliefs. You of course have to trust people to want to do the right thing and to be prepared to change based on new knowledge and new interactions.

Complexity theory is not the same as “systems thinking” theory — the [Peter] Senge stuff is “reductionist and linear”. Complexity suggests that what people think or believe doesn’t matter as much as their communications and interactions. But you want to manage the interactions at some reasonable scale to make a real difference, and you scale changes in a complex adaptive system by decomposition and recombination, not by imitation or replication. [I would like to hear more about this. It seems to be about breaking the new behaviour down into its building blocks, and then letting each group/organization you want to encourage it in to reassemble them in a way that makes sense in their particular context. The way nature scales/learns/evolves without exact replication. “Here’s a new idea that seems to work. Here are its ingredients. See if makes sense to apply it there.”]

Complexity science, the science of understanding living systems, has been “debased and demeaned” by popularizers that have dumbed down its true meaning. There is “great danger in trivializing theory”. And in relying on theory to the point of exclusion of empirical facts that contradict the theory.

Systems dynamics is an engineering metaphor (about planning and goal-setting) whereas complexity is an ecological metaphor — where are we now and what can we do next. Systems thinking starts with a goal, a mission, a statement of purpose, while complexity starts instead [more humbly and pragmatically] with a “sense of direction”.

And complexity doesn’t try to think about the system as a whole, since we can never know it completely; instead you think about the identities and agents and interactions in play and what are the constraints and which of them can be managed. In an ordered system you manage the outcome, but in a complex system you can only manage [some of] the constraints.

Complexity is about “managing energy gradients”, eg by making it easier [and/or more fun?] for people to act, right now.

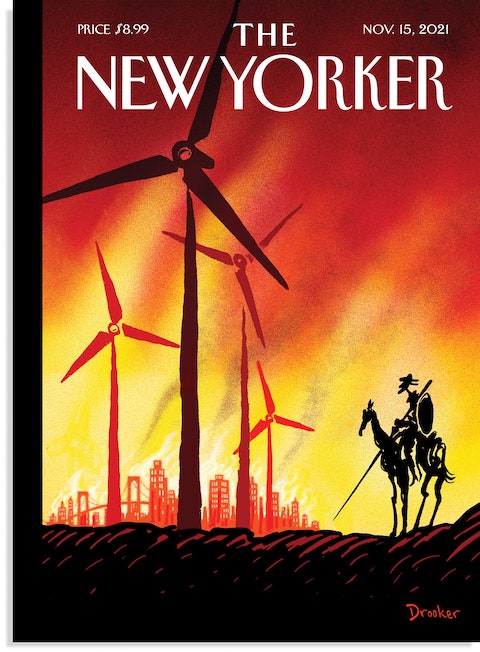

We need to look for “the opportunity for catalytic events to trigger phase shifts”, especially in areas like climate change. That will only happen with substantially more interaction between people across silos who can then see what they have in common and agree upon things as being important enough to require immediate action. [Dave had hoped, last year, that there would be a significant intersection and common cause emerging between the fight against CoVid-19, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the Extinction Rebellion movement.]

We don’t live in a mechanistic world, as much as ‘management scientists’ would like to believe otherwise, especially when urgent crises shift our thinking back to mechanistic solutions and to things that seemed to work in the past. Every software engineer needs to learn history, and ethics.

There’s also a danger that well-meaning ‘mediators’ can actually interfere with this process of intimate contextual entanglement necessary to deal effectively with complex situations. It takes skilled facilitation to stay out of the way of it, while also enabling it to happen.

Meaning-making is an abductive process. Abductive thinking entails the capacity to see things from different trans-contextual perspectives, to listen empathetically and pay attention to outliers on the “margins of meaning”, and imagine novel approaches and ideas, to draw on the “logic of hunches” and intuition, to rest in uncertainty and welcome and play with ambiguity, to combine well-considered theory with direct experience. It requires lots of practice, good attention skills, and rigour. And a practiced capacity to hypothesize, and to test our hypotheses, and hold several hypotheses simultaneously. And a capacity for “small noticings” — such as noticing the light on the field during a journey that you didn’t realize was important until you’d passed it, and then turning back to give it more attention.

So, for example, listening to the narratives about a child who is struggling in school must focus not only on the teacher’s skills and style and the child’s cognitive capacities, but also on complex factors like the child’s nutrition and home environment.

Many indigenous cultures deal with complex predicaments by bringing people together to do things, including ritual, and to engage with each other such that their contexts, understandings and narratives become entangled. They surface and share common concerns instead of debating or mediating differences. Then they can safely enter into intimate conversations. And then they trust each other to do, with the best of their shared understanding, what they know must be done.

But you don’t need a crisis to use this abductive process. You can understand and manage the constraints in a system even if it’s far from collapse. You can be hopeful, and more rigorous, applying it in all we do, without having to be optimistic about outcomes. It’s not about outcomes, which are largely outside our control or ability to predict. You can’t engineer emergent properties.

On ritual: The ritual of surgeons scrubbing up together before surgery can be as essential to its success as the surgeons’ knowledge. Offering true gifts, with no expectation of reciprocation or even acknowledgement, are among the most important rituals.

We live in a world of people too busy to be interested in history and science, and lacking in curiosity. And we have too many specialists and not enough generalists. We live in a world of cognitive malnourishment. Things like art and music are cognitive activators. So is communal living, engaging with the ambiguity of language, and practicing arguing a point of view you don’t believe in.

It is our relationships, including serendipitous encounters, that habituate us, far more than our environment and the resources we have at our disposal. The anxiety of feeling that we must “solve the problem” distracts us from thinking creatively and abductively about it, and leads us to fall back on habituated responses.

Part of our task in sense-making in complex situations is eponipoesis [sp?] — naming the unseen, what we tacitly realized but had never articulated out loud. Another part is having a powerful sense of the numinous, the mysterious — and of awe.

_______

So what do we make of all this, especially if one believes, as I currently do, that we are conditioned creatures lacking free will?

I think, perhaps surprisingly, that they’re absolutely correct. I have often been told that my “distinctive competency” in life is imagining possibilities that very few would ever have come up with — evidently an abductive skill. But I had no choice in the matter. I am by nature a curious generalist with an exceptional imagination, for better and for worse. This competency is one I came by naturally, and I practiced it because it was apparently valued, so I have retained it. Sometimes it had even enabled me to name the unseen.

I have poor attention skills, also conditioned, I believe — in part because of long-standing childhood fear, based on some relatively mildly traumatic experiences, that if I really paid attention I would be horrified, so I taught myself to turn away, to not pay attention. Now I’m trying to pay better attention, but it doesn’t come easily, and even my attempts are driven by my conditioning — now I don’t want to hurt people I care about by missing their signals. But I’m still a slow learner, and slow on the uptake of “small noticings”.

It makes sense that, once people believe what they want to believe (ie what they’ve been conditioned to believe, how they’ve come to make sense of the world), it’s exceedingly difficult to change their beliefs by directly confronting them with facts. Stories can be more effective, but bringing people into a relationship (not against their will, of course) that will give them context to understand why someone believes something very different from what they believe, is almost certainly more effective still. Our relationships ‘recondition’ us, over time.

I’m not sure about the value of rituals. They are clearly useful and important to many. And to the extent a ritual (short of harrowing ones like hazing, which can be effective but also traumatizing, a poor trade-off) can facilitate a shared experience, a commonality of context and meaning, I can see how they could facilitate a lot of otherwise-challenging or otherwise-awkward actions — dancing being an obvious example, whole-body shared experiences.

This discussion did resolve some great uncertainties I’ve had about systems theory and particularly about systems diagrams — the impossibility of knowing all the variables (in complex systems), and the dangers of asserting causality when there are so many variables. From now on I am going to use them more cautiously.

I’m dubious about the whole prospect of ‘scaling’ change. Dave’s nature-based model of recombination is intellectually appealing, but social and biological systems are different, and I find the metaphor weak. I’d believe it more if there were examples of its successful application, but I suspect it is still mostly theory. If social change doesn’t scale, as I suspect, a lot of businesses, and socio-political groups, will, I think, quickly lose interest in projects based on it.

I very much like the idea of practicing the development of, and the simultaneous holding of, alternative hypotheses, that sits at the heart of abductive process. I’m adding it to my Schmachtenberger homework. (And obviously I like the whole “managing energy gradients” idea, since it echoes Pollard’s Law of Human Behaviour.)

And very much onside on the subject of cognitive malnourishment. On the whole, I don’t think modern society values cognitive capacity or wants people to think smarter or to become more self-knowledgeable or resilient. Our consumer economy encourages dependence and the infantilization of humanity, because it’s more profitable, and reduces resistance to the status quo and existing wealth and power structures. Sad, and understandable.

And of course seeing new places with people with different values, cultures and sensibilities is always enriching. But, as the Procol Harum song says, whenever I’ve gone away travelling, I “only saw how far I am from home”.

Thanks to Dave and Nora for putting this on. Dave’s always been brilliant, but his talks and writing have become more coherent in recent years, though it’s still a challenge to follow his mental leaps. Maybe his voice is finally catching up to his brain. He famously said “we know more than we can ever say”.

And Nora, with a smile, said during the conversation, referring to no one in particular, “what we hear is not what was said”. Eliot would have smiled, too.

EDIT Dec 4: The video of this conversation is now online.

EDIT Dec 9: The Cynefin team has provided these links to more resources on this subject: