This is a follow-up to my story The Fortune Teller. It is a work of fiction.

It was raining, and the strain of the pandemic and all the extra things to remember was finally getting to me. I’d just come out of the grocery store, where half the things I’d gone to buy were out of stock. And on top of it all, when I got to my car there was a piece of paper on my windshield. I scowled: It would either be a parking ticket, undeserved, or advertising, unwanted.

I put the groceries in the car, snatched the paper off the windshield, climbed inside, removed my mask, took off my fogged-up glasses, and used the alcohol solution in my glove compartment to clean my hands. Finally, I picked up the paper and opened it up.

Here is what it read:

Hello again. It has been a while. I think you might need a reminder of some things you agreed to do:

1. Smile. Genuinely. All the time. Doesn’t matter if you’re with people or alone. It’s a muscle worth exercising. It will change how you relate to the world.

2. Pay attention and notice. Notice the details, the qualities, of light and sound and texture and taste and scent, and more, with your whole being. Just that, leaving no room for thinking about what it means.

3. Eye contact. When you meet people, really look into their eyes until you see. Don’t think about it — just notice, pay attention. This is not about staring, it’s about observing. Notice movements of the eyes and face, but do so with your senses and intuition — don’t try to interpret them.

It’ll do you good.

We’ll be watching.

Memories of the enigmatic young fortune-teller at the lemonade stand — what was it, two years ago? — came rushing back. I looked around to see if the fortune-teller was still around, and I saw a flash of motion behind me, but by the time I exited my car, there was no one there.

I turned the key to start the car, and turned on the defroster since the rain had fogged up the windshield too. My glasses and my windshield, both blurred to the point I could no longer see. Was there a message in that?

I slumped back, waiting for the inside to clear, and thought about the message. She had given me these three instructions, supposedly “from the faeries”. I had practiced them faithfully for a few months and they had made an enormous difference in my life. Why had I stopped? And how did my fortune-teller know?

The likely answer to the latter question was: I had probably encountered her somewhere, recently, and was so preoccupied, so inattentive, so unpracticed at making eye-contact, that I didn’t recognize her.

I still had the post-it note pad in my glove compartment that I used when inspiration for blog articles came to me while I was driving. I pulled it out, and made a pencil sketch of a face smiling, with one eye focused on a bird and the other on the eyes of another person. And big, listening ears! I stuck it on my dashboard. I smiled. I looked around, inside my car and then outside. And I put the car in gear and drove home.

Why had I stopped doing these things? In my complacency, my imaginative flights of fancy, my predilection for the conceptual over the perceptual, my habit of hiding inside my own head, was I becoming once again disengaged from the real world? Had I given up on it?

I arrived home with no memory of how I got there. And yet, for the first time in a while, I had noticed some things along the way that I hadn’t noticed before. The distinctive colour of the cedar trees. A swarm of birds flying overhead along the road. The sound of my own breath.

When I retrieved my groceries and started towards the house, I thought I was hallucinating. The fortune-teller, wearing the same too-old-for-her outfit, complete with head-scarf, was sitting in a chair on my front deck, stroking my neighbour’s cat (which had never let me even get close to it). The cat was sitting in her lap, blinking contentedly. I could tell my fortune-teller was smiling at me even with her CoVid-19 mask on. Her mask had cat whiskers drawn on it, along with the single word: Breathe.

I looked at her rather sheepishly, raised a “wait a moment” finger signal, went inside, put away the groceries, washed my hands, put on a new mask, cut up two apples into slices in separate bowls, and went back outside, offering one of the bowls to her, before moving a deck chair about ten feet from her and sitting down and nodding. My invisible smile was genuine.

She nodded a “thank you” and we ate the apple slices in silence. I filled my now-empty bowl with water for the cat and put it down near me. The cat, of course, ignored it.

I thought about the important lessons her three “instructions” had taught me:

- That when you smile, in an unforced way, your brain actually starts paying more attention to what’s going on “outside” it, in an attempt to rationalize why you are smiling, until it finds something worth smiling about.

- That smiling therefore shifts your brain from a conceiving (thinking, abstracting, judging) to a perceiving (instinctive, noticing, appreciating) mode. Definite improvement!

- That time seems to move more slowly when you’re more attentive.

- And that the distinction between you and “everything else” blurs when you spend less time thinking about yourself.

It was a bit chilly, so I retrieved a couple of blankets and passed one to her. The cat jumped down from her lap while she positioned it, and then immediately jumped back up and settled back in. I had the strange sense that the girl and the cat were somehow “connected” — it was as if they knew each other’s thoughts and feelings and were extensions of each other. The cat had never looked at me that way. At least, not that I’d noticed.

I was preparing to break the silence, to apologize for having “forgotten” the three “instructions”, but instead, something made me just look back and forth between the girl’s eyes and the cat’s body.

So she finally spoke first: “I’m sorry”, she said. “I should appreciate that you’re scared, and it was unfair of me to chastise you.”

“Not unfair”, I replied. “Generous, perceptive, observant, compassionate.”

I could read a smile and surprise in her eyes. How much more important eye-contact is when you must keep the rest of your face covered! She said: “But also unfair.”

I thought for a moment and then said: “I have come to believe we have no free will or choice over what we do, or don’t do. But that doesn’t mean you aren’t right in your observation.”

“I guess I was hoping that the reminder might somehow ‘recondition’ you, since you did follow its advice the first time it was offered. But not only is that unfair, it’s a bit condescending.”

“Everything we do, and every circumstance that arises in the moment, reconditions us. It’s not like you’re in advertising, or PR, or politics, or the media, or religion, using conditioning to manipulate others for your own purposes. Your windshield reminder may have just reconditioned me to inevitably do something different from what I was inevitably going to do without it. You changed the circumstances of the moment. It’s actually you who had no choice but to leave the reminder for me. So thank you.”

We looked in each other’s eyes, and while I could see the smile in hers, she lowered her eyes almost shyly and said:

“Are you ready to consider some more thoughts I can’t help but have, and which I may have no choice but to offer, unless you change the circumstances of the moment by telling me I shouldn’t?”

Her look was playful, not sarcastic. So much can be read in the eyes, so unambiguously, when you stop thinking and judging and just let the communication happen!

“Sure,” I replied, smiling back. “As long as you first tell me how you know I’m scared.”

She laughed. “Well,” she replied I could say that it’s a safe bet, since everyone is. But the difference with you is that, unlike most people, you know you’re lost and scared and bewildered. You telegraph it. And that’s why I said it. Because we both know it’s true.”

It was my turn to laugh. “Fair enough. OK, hit me with some more ‘instructions’, but remember, I can only handle so much at once.”

I didn’t need to look to know she was sticking out her tongue at me. She had told me this, about my limited capacity for new learning, back at our first meeting. And she was absolutely right.

“OK then,” she said, after a long pause. “Number 4: Listen beyond what is being said to where what is said comes from.” She paused to let that sink in, and then added: “Language is a terribly, desperately clumsy tool for communication, and we almost never say what we really mean. We can’t help it. We usually don’t know what we really mean, even if we had the right words to convey it. The feeling behind what is said is what to pay attention to. It’s what the communication is actually about. And, again, noticing, eye contact, and even smiling can help you sense that feeling, which is what you really want to address.”

I thought about this for a moment and then said: “OK, then help me out. What was the feeling behind what you just said to me? See if I picked up on it right.”

She nodded, and then said, with her usual bluntness, and looking me right in the eye: “I feel sorry that you’re scared, and that you’re scared for no sensible reason.”

She told me with her eyes what my reaction told her with mine: that I’d guessed her response, mostly, correctly.

And then her eyes filled with tears and she added: “You’re like an old bird who has always been caged, and now, at least a little free, you’re learning, very clumsily, how to fly.”

I teared up a bit too, and then said to her: “There are many far more ‘caged’ than I am. They need your counsel more than I do. So why me?”

“Because you’re ready to listen.”

Without rising, I did our signature palms-together bow, and she returned the gesture.

“The thing is,” she continued, “when people talk, they’re looking for appreciation, attention, and reassurance. They don’t really care about communicating, unless that’s a means to one of those three ends. When people challenge or question something you’ve said or done, what they’re really saying is: Help me fit what you’re saying (or doing) into my frame, my worldview. They want to make sense of it. Beyond that, its meaning is unimportant, and all that is important is understanding and reflecting back the feeling behind what they are saying. That’s really all that language can hope, at best, to communicate.”

I looked at her eyes, and then watched her skritching the cat. “Wow, that’s very profound. I think I get that, but maybe that’s all I can handle for now. I’ll have to think about this. I’m a slow learner, you know.” I looked up at her and smiled, playfully.

She laughed again. “That’s why I’ve written it down this time”, she said, holding up a piece of paper.

I just shook my head. “So there’s more?” I asked. She nodded. I shrugged.

“Number 5. This one’s simple. You have to get out more. You know in your head that everything is one, yet you are way too much apart. Too much time playing on your own, indoors.”

I put out my hands in a gesture of protestation. She could see my frown. I said: “Well… I don’t really like people all that much. I kinda prefer my own company most of the time. And much of the time the weather isn’t that great for being outdoors. I love my creature comforts.”

“Then bundle up. Buy some clothes that are warm and waterproof without being heavy or constraining. Get out and spend time with non-human life. The entire natural world, it’s all talking to you, showing you things, and a lot more eloquently and generously than humans do. Go listen, really notice, smile, and when you see deer or birds, make eye contact, gently. Pay attention and you’ll probably be a lot less scared, and maybe even less lost. Listen to the wind. Notice the colours of moss and rocks. Say hello to the more-than-human world.”

I nodded. “Sure, if I can make time for exercise every week, which I don’t particularly like, then no reason I can’t make time for that.”

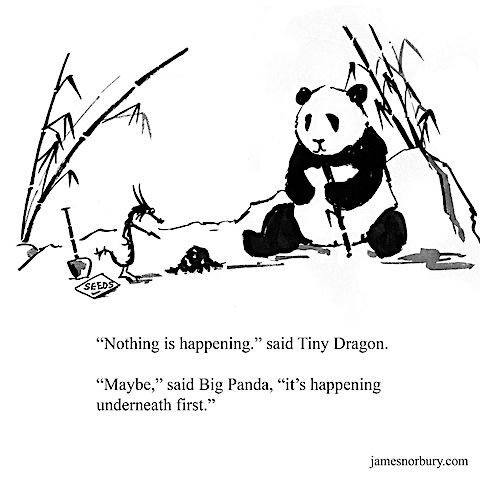

“Yay!” she replied. Last one — Number 6. Let wild creatures show you that there are only two natural states — equanimity and enthusiasm. Everything else — fear, rage, panic — is just a temporary aberration.” She pointed at the cat.

I pondered again, and then said: “That’s an awesome observation. Can I use that in my writing?”

“As long as you agree to explore to see that it’s really true. It took me a long time to figure out. Humans are so rarely in this natural state that when it happens it seems unnatural, worrisome. We are chronically in unnatural states, conditioned into them by other humans. It’s no wonder wild creatures treat us with such great caution. And no wonder you don’t like other humans very much!”

I shook my head. “I’m concerned that that might just reinforce my sense that it’s utterly hopeless for human beings, that we’re all hopelessly broken and spend our lives just struggling to heal a bit and then die. If there’s no path to that ‘natural state’ that wild creatures live most of their lives in, what’s the point of knowing about it?”

“Isn’t it better to know the truth?”

“I don’t know. We believe in the truth we want to believe in, and sometimes I think that’s the only way we can stay sane. Do you live most of your life in that ‘natural state’ — equanimity and enthusiasm?”

“Hah! If only! Nope, I’m just another struggling human. I know about it only because the faeries told me. I know it’s right, but I can only know, I cannot really live in that world.”

“I though you said there were no real faeries?”

“Do you remember what else I said about them?”

“A metaphor for ‘that which must be told’, the knowledge that emerges, inevitably… if you’re paying attention.”

“Very good. Then you know the answer to your question. But you haven’t answered mine.”

I closed my eyes, and just breathed. “Hmmm. Isn’t it better to know? I don’t know. If we have no choice, it seems the question is moot. Some will know, and others never will. It makes no difference.”

“Ah, yes and no. Remember the Star Thrower story?”

I laughed. “It made a difference for that one.”

I looked up, and she was gone. The cat was sitting on the blanket, looking at me quizzically.

Under its paw was a piece of paper with instructions 4-6 written on it. I picked it up, skritched the cat, noticed with some astonishment that it let me do so, and, with a smile, walked into the house.

image by tumisu at pixabay, CC0, photoshopped