This is the 16th in a series of articles on CoVid-19. I am not a medical expert, but have worked with epidemiologists and have some expertise in research, data analysis and statistics. I am producing these articles in the belief that reasonably researched writing on this topic can’t help but be an improvement over the firehose of misinformation that represents far too much of what is being presented on this topic in social (and some other) media.

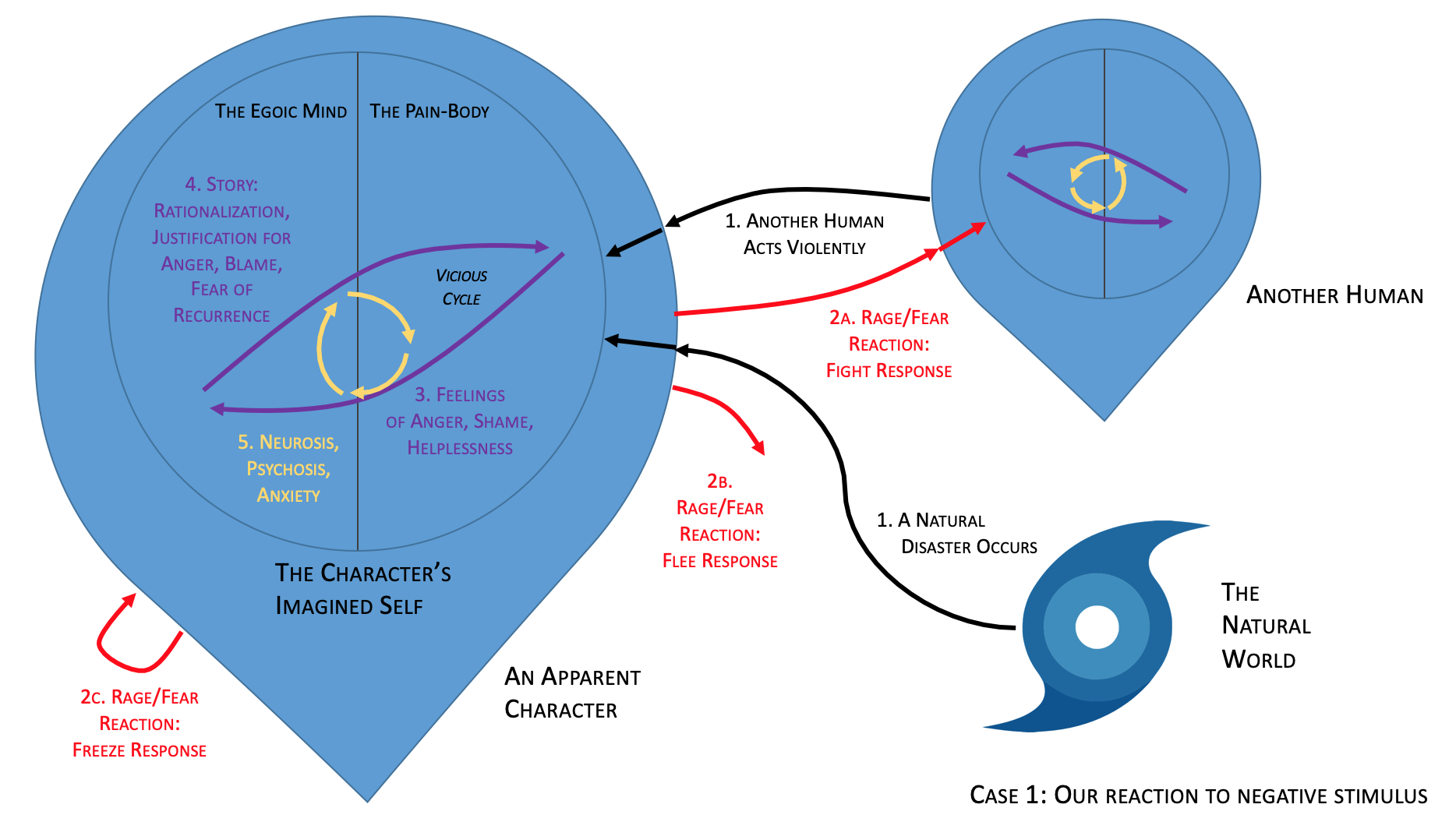

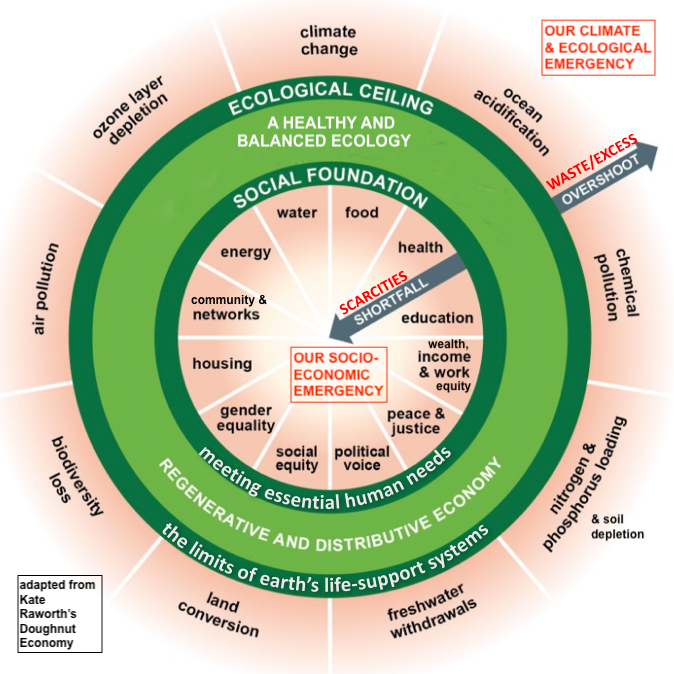

There are a lot of chronic diseases — major killers of those of us in affluent nations — that are, even adjusting for average life-expectancy and underreporting, relatively unknown in the world’s struggling nations. Many of these are autoimmune diseases, chronic diseases that we get, or are unable to shake, because our immune systems overreact — they are so unpracticed at distinguishing between harmful and healthy cells that they attack both, usually excessively, since they “don’t know when to quit”. It was such a reaction that caused most of the deadly second-wave 1918 pandemic deaths — not the virus itself.

There are three main causes behind our bodies’ immune systems’ malfunctions: The first is immunodeficiency, when our immune systems are weakened by toxins or diseases (or deliberately by immunosuppressant drugs like steroids), and hence are unable to do their job. The second and third are causes of autoimmune (hyperactivity) malfunctions — nutritional deficiencies that starve our bodies of nutrients the immune system needs to function properly, or disrupt them with unnatural chemicals; and antimicrobial chemicals that kill parts of the immune system, usually “collateral damage” in the fight against disease, but also from environmental exposure to pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals.

I’ve written at length about our nutritional deficiencies over the years, and if you want a great recap of the connection between these deficiencies and our health, here’s a great summary. In this article I want to focus on the third cause — antimicrobial chemicals.

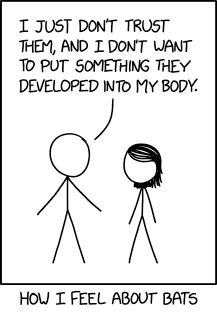

Antimicrobials include the whole array of things we use to kill other living things that we consider dangerous or just don’t want to put up with — antibiotics (antibacterials), antivirals, antifungals, antiparasitics, as well as pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and the many other substances that we apply to other living things, and to the surfaces of our homes and other buildings, that we then ingest indirectly by eating, touching or breathing them in. For the most part we use these substances liberally despite having little or no idea about their long-term negative effects on our health. But these substances are “antibiotics” — their purpose is to kill life forms, and since most of the DNA in our bodies is bacterial, it should be obvious that they are hazardous.

It is, of course, a balancing act. Several ghastly deadly human diseases have been either eradicated or are kept in check through the use of antimicrobials. But trying to fight microbes is a losing proposition — they outnumber us, they’ve been around a thousand times longer, they mutate with breathtaking speed, and under the right circumstances they can migrate around the world in a matter of days. And they are part of us, and an essential part of what keeps us healthy.

There is growing evidence that our overuse of antimicrobials and other “cleaning” chemicals is creating some nightmarish problems. Their use drives the microbes to adapt more quickly, developing immunity to our antibiotics and other antimicrobials to the point we are now running out of alternatives to deal with “resistant” strains, leaving us defenceless when these strains emerge. The arms race to keep ahead of new strains of pneumonia, tuberculosis, e. coli, salmonella, VD bacteria, c. dif, necrotizing fasciitis bacteria, and staphylococcus by inventing new antimicrobials is a losing game, and options are running out.

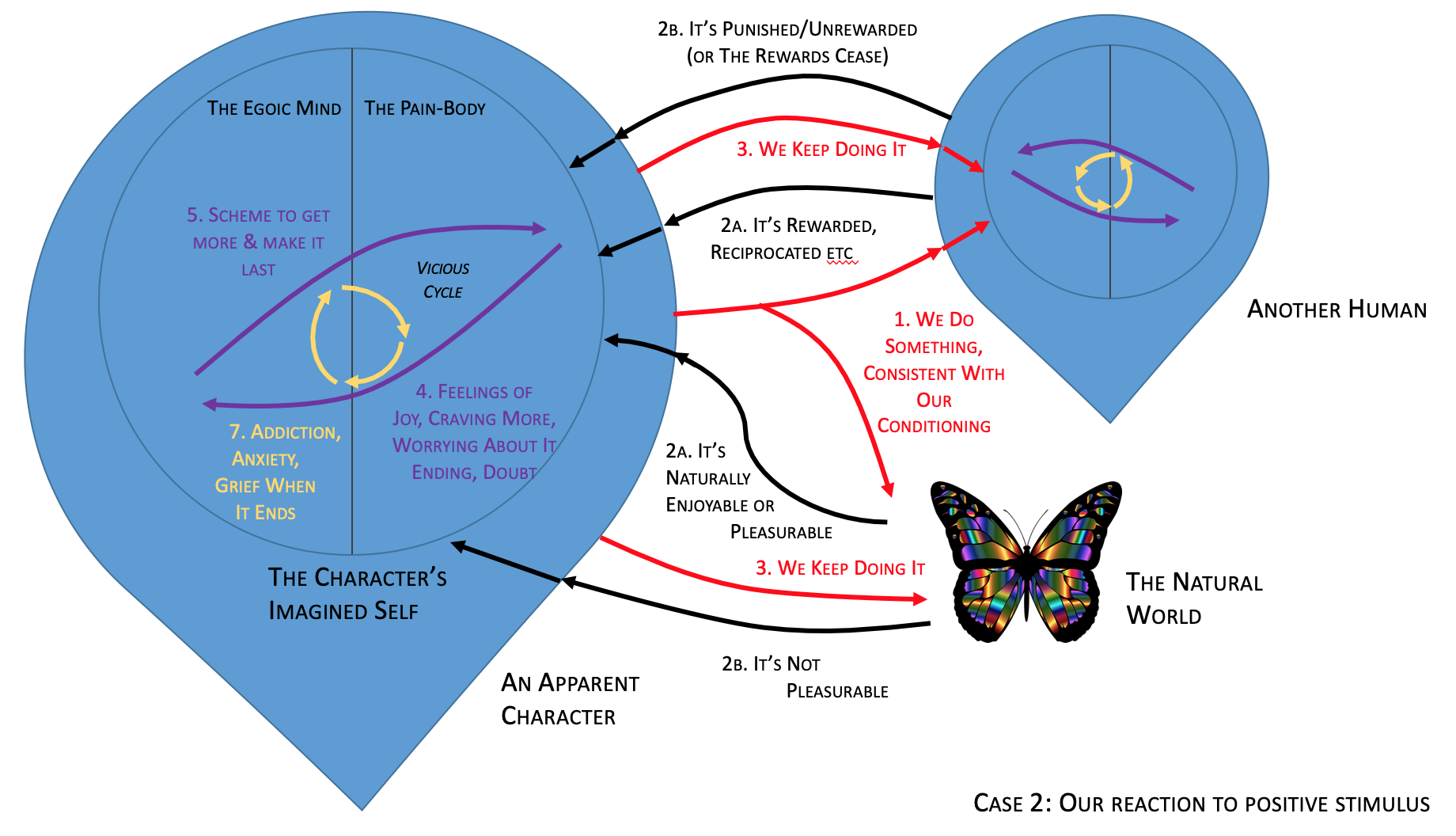

The explosion in crippling diseases caused by disabled or hyperactive immune reactions has led to calls for those of us in affluent nations to stop “sterilizing” everything and let our immune systems be naturally exposed to microbes of all types so they can “learn” to function properly.

There is evidence, for example, that what is behind the recent massive increase in people with serious allergies to pet dander and some foods, is parents’ well-meaning decision to prevent their young children from any exposure to substances that might provoke an allergic reaction. Paradoxically, that lack of exposure is precisely why so many children, and now adults, have debilitated immune systems that never learned to cope with these substances, and now suffer lifelong with every exposure to them.

For ten years I was prescribed, with the best of my doctors’ intentions, a massive oral dose of tetracycline antibiotic to treat a particularly miserable case of acne. The result is that my gut’s immune system was ravaged, and I believe that is why I eventually contracted ulcerative colitis, an autoimmune disease of the colon. With proper diet and extremely limited use of antimicrobials I have now been symptom-free for over a decade, but my immune system will likely never fully recover.

Those with prolonged severe colitis have resorted to what might seem a bizarre and dangerous treatment — fecal transplants deliberately intended to infect them with intestinal worms imported from Africa. It seems these worms were endemic to humans until the modern antibiotic era, and this disease was and is largely unheard of in places where the worms were found. The theory (which of course western doctors won’t hear of) is that the worms co-evolved with us and are an essential part of the human gut ecosystem. And when we decided they were ‘bad’, we ushered in a range of new intestinal diseases our immune systems couldn’t deal with.

And don’t get me started on the antimicrobials we force-feed and spray on and around factory farmed animals in confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Nothing like providing babies with cow’s milk that has none of the natural immunity benefits of mother’s milk plus an extra dose of chemical antimicrobials and hormones. No wonder so many of us grow up with crippled immune systems.

Such is the balancing act. And now we’re in the midst of another pandemic, likely just a trial run for the really virulent pandemic that we’re likely to face in the near future. And we’re showing just how (unintentionally) incompetent we can be at trying to manage it.

My sense is that, especially in places where we use the most antimicrobials and similar toxic chemicals, we have become much more vulnerable not only to autoimmune diseases, but also to infectious (including pandemic) diseases.

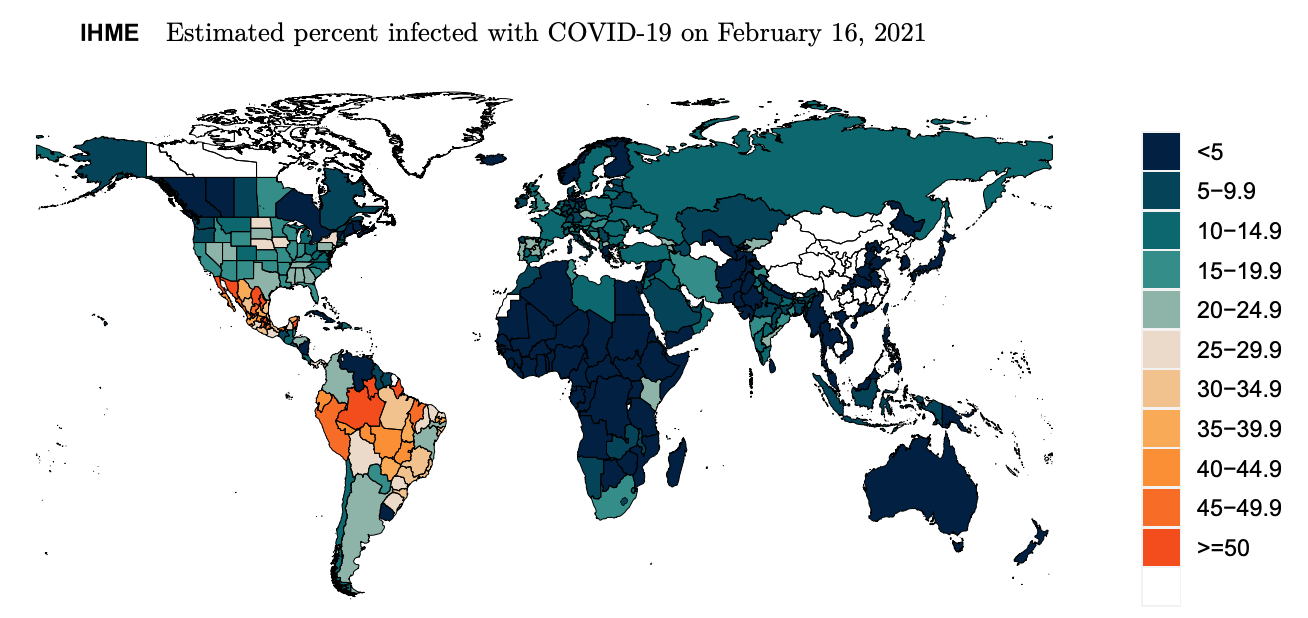

Take a look at the map above, which shows the stark contrast between per-capita CoVid-19 death rates in the Americas and Europe, versus the rates in most of the rest of the world. It’s as if there are two different pandemics at work.

New York doctor and Pulitzer-winning biologist Siddhartha Mukherjee has just published an article pointing out this great mystery about the hugely uneven global distribution of the pandemic. Countries like India and Nigeria have per-capita death rates as much as two orders of magnitude less than those of the Americas and Europe. He dispenses with the usual explanations (under-reporting, misdiagnosis, demographic structure, government response, climate, “spacial distribution of the elderly”, family size, household size, population density, time delays, mobility), which may explain part but cannot explain anywhere near all of the variation. Why would Brazil, India and Nigeria, which are similar in climate, demographics and almost all of the above “usual factors”, have such staggeringly different death rates?

Just to demonstrate how anomalous this is, consider a 2006 study predicting the potential impact of a 1918-comparable novel “bird flu” (non-corona) virus happening that year. Their predictions are almost the exact opposite of what has happened with CoVid-19 — most bird flu victims, they predicted, will be in India and Sub-Saharan Africa, mostly people in their teens to thirties, and relatively few will be in the Americas and Europe.

Siddhartha wisely refuses to suggest any Occam’s razor explanation for the anomalous carnage of CoVid-19. But he does suggest one reason that is much more compelling than the usual ones: That the people in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have a much stronger natural immunity due to previous exposure to other coronaviruses and infectious diseases.

Map from IHME showing their estimates of infections by country to date. Some recent studies suggest that this map would more accurately show almost all of Africa and South Asia as bright orange, and the rest of countries three shades “oranger”, on the basis that global infections (most of them asymptomatic) are actually at least 5x higher than IHME estimates. And that the IFE varies by country by up to an order of magnitude depending on the health, and “experience” of its citizens’ immune systems.

Indeed, while they have been dismissed as improbable, epidemiological studies have repeatedly indicated that more than half the people tested in countries in these areas had markers indicating they had been infected with CoVid-19, though the vast majority were asymptomatic. This correlates with WHO studies, similarly discredited, suggesting that five times as many people have been infected globally as the IHME and other modellers have estimated, and that the infection fatality rate (IFR) is commensurately lower (as low as 0.15% globally). That would break down to about 0.80% in Europe, the Americas, South Africa, and Australia/NZ, and only about 0.08% in most of the rest of the world.

The implications of this are quite staggering. They suggest that in much of the world, notably excluding countries that have worked the hardest to minimize exposure from the outset, we are well along the way to, if not already at, herd immunity levels. They suggest that, really, only those in the Americas and Europe, with their ten-times-higher IFRs, will see a really dramatic benefit from the current vaccines. It’s too early to say this is true for sure, but if it is, it will upset all our assumptions about pandemic risk and transmission.

So what does it mean to say the people in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have a much stronger natural immunity due to previous exposure to other coronaviruses and infectious diseases? I would suggest it means that:

(1) their immune systems have not been weakened by toxins and diseases that cause immunodeficiency, or by our western diet’s nutritional deficiencies or antimicrobial and other “cleaning” chemicals that render the immune system unable to respond properly to microbial infections, AND

(2) their immune systems have actually had to deal with a wide variety of microbial infections in past, and now are resilient enough to deal with novel infections like CoVid-19. Not immune, but resilient.

I think it’s plausible to believe that reason (1) explains the high IFR of CoVid-19 in North America and Europe, where our immune systems are compromised and impoverished, and (2) explains the high IFR both in Latin America and among many indigenous peoples around the world, where their immune systems have never encountered this type of infection and hence are unable to cope with it.

It’s important to remember that a significant part of our “natural” immunity is inherited, passed down from generation to generation. When a woman is breast feeding a sick child her body will actually sample the child’s saliva, create an immune response, and put antibodies in the breast milk specific to the child’s illness.

I wonder, if CoVid-19 had been a 1920 pandemic instead of a 2020 pandemic, whether the IFR would have been very different in many areas, not because of the virus itself, but because of how our less-compromised immune systems would have handled it.

In the end, the mystery of CoVid-19 rests as much within our bodies as in the workings of the disease. And they have evolved, and will continue to evolve, together. But, just as we cannot continue to overlook our nutritionally poor and poisoned diets as a huge contributor to our diseases and suffering, we cannot keep overlooking the damage done by our excessive use of antimicrobials, and by all the other ways we damage and deprive our immune systems of the “learning” that they need to help us get, and stay, healthy.

To the Thawing Wind

To the Thawing Wind

|

|