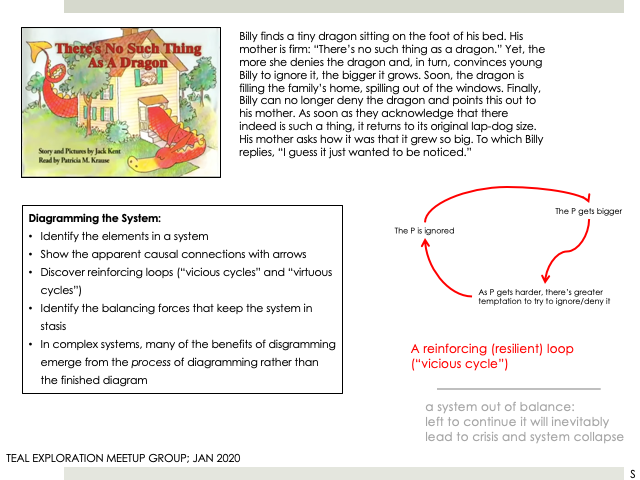

This clip is an 8-second excerpt of a short doc by Journey to the Microcosmos; this is almost exactly what I see under my little microscope

I am watching a couple of tardigrades — an animal quite distinct from any other in existence — under a microscope. They’re only about 1/2 mm long, but under the 150x lens of my $19 microscope they’re easy to see, and, if you start with wet moss, pretty easy to find too (they actively toss the moss around looking for food, so you just look for movement and there they are). They have 8 clawed legs, distinct heads, two ‘eyes’, brains, complete digestive and nervous systems, muscles (but no bones), and blood cells, but no one knows how they actually breathe or circulate blood and oxygen (they have no heart, lungs or veins). They’ve been around about a half billion years, can live over 100 years, and can contract into a dormant ‘tun’ state when living conditions are unfavourable, for an almost indefinite period, returning to life as conditions improve. And they are everywhere.

They give me pause, even though in many ways they’re much less strange than larger and equally ancient creatures like jellyfish and bats.

When I look at the tardigrades, I realize that, inside this body, there’s a similar world of billions of tiny creatures making me what I ‘am’. And that what ‘I’ am is not a creature, but a complicity of billions of creatures, gathered together in a shell called ‘skin’, just like the tardigrade. To call the collective within that skin a ‘creature’ is a mis-conception, a convenient naming convention, but nevertheless a lie. We apparent humans seem to use that convention in an honest and understandable attempt to make sense of things.

But that isn’t quite right. The thing that is trying to make sense of things, apparently, is the brain. The impossible complexity within what we label the digestive system also makes sense of things, usually quite brilliantly thanks to the billions of years of conditioned ‘knowledge’ in its DNA, and thanks to its experience (which, sadly, in the modern human body is horrifically limited due to the impoverished nutrition of homogenized and sterilized industrial agriculture, and to our equally sterilized, diminished living ‘environments’).

Making sense of things is what the brain does, and in very large and complex brains it does this in part by abstraction. It looks for patterns, invents models, and tries them out. Because this process is so slow, and so energy-intensive, it is unlikely it would have evolved as a survival system; until we fucked up their ecosystems, many species with large brain capacity thrived without any apparent need to abstract anything. Their brains instead serve almost exclusively (as ours used to) as what Stewart & Cohen call a centralized “feature detection system”.

Creatures like jellyfish have a highly-effective feature detection system, but it is distributed throughout their bodies rather than centred in one specialized processing ‘centre’. The fact they have been around for 650 million years while humans are still struggling with our first million, suggests their sense-making might be at least as good as ours.

As I’ve mentioned before, my hypothesis is that the abstracting capacity of large centralized brains was a spandrel, an unintended consequence of the growth of brains that occurred when we apes left our home in the trees of the rainforest and went to the sea, with its more moderate climate and its abundance of protein-rich foods. Human creatures never needed large brains in the rainforest that was our home for most of our million years on the planet — everything we needed was in abundance and in arms’ reach.

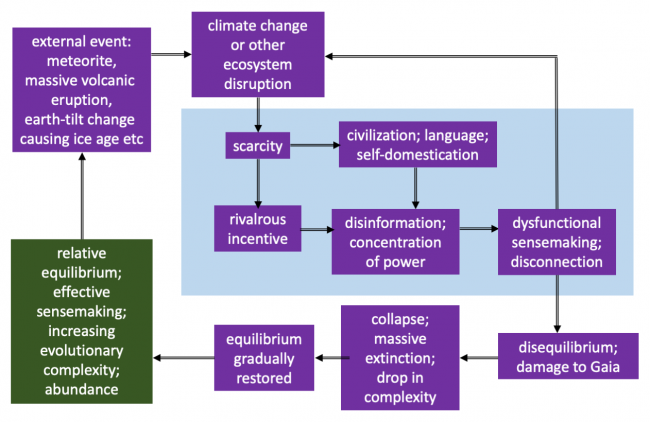

But when we left our forest Eden, likely because of drastic climate change (ice ages, catastrophic cosmic radiation etc), our survival depended now on a capacity to adapt to many different and new threats and environments. Early human ‘civilizations’ generally popped up in coastal and marine areas where there was an abundance of protein rich seafood. So my hypothesis is that our new protein-rich diets expanded our brains’ capacities, and that such expanded capacities were essential to our species’ survival (we apparently reached numbers as low as a few thousand humans in the transition, and lived almost exclusively by the sea).

These new larger brains would have some essential qualities — an ability to memorize more types of food, more places, and more diverse dangers. One such new memory would have been the discovery that after catastrophes (fires, floods etc) there would briefly be an abundance of a few homogenous plants, before successor species and the planet’s natural propensity for increasing diversity and complexity again took hold. What would have gone through the growing brains of prehistoric humans witnessing this? The fact that continually disturbing that diversity (via irrigation, the use of human-made fires, weeding etc) might allow that abundance of one type of food to continue indefinitely. Thence was born, I would posit, what is called catastrophic (monoculture, high-intervention) agriculture, enabling (indeed, requiring) the first human settlements. And in fact, this is seemingly how human civilizations began, independently in many places around the globe, and likely before language or other abstract inventions came into being.

So, I would argue, the capacity of abstraction wasn’t necessary for any of this to happen — just brains large enough to manage a greater diversity of memories, patterns and sense-making.

But such brains are capable of abstraction, and as long as the creatures with these brains were thriving on their new seafood diets, the capacity for abstraction was, I would suggest, inevitably going to be one of the experiments that nature tried out. Even if it was completely unnecessary, if it survived in these new larger brains, this new capacity was going to hang around. In that sense it’s analogous to sex and death — qualities that jellyfish and tardigrades show us really aren’t essential to a species’ or ecosystem’s capacity to thrive. They were never needed, but because the creatures that had them thrived, so did those amazing, dreadful characteristics.

So our brains evolved the capacity to abstract their environments in a very simplified model — to create the concepts of space and time as placeholders for their increasingly sophisticated memories, and then to begin to conceive of cause and effect — patterns that seemed correlated in space and time, and to start to ‘predict’ what might happen in an abstracted ‘future’. No matter that these models and predictions and the ideas, thoughts and feelings they provoked, were illusory and useless (too simplified, too slow) — the brain had evolved the capacity to notice features and patterns and make sense of them, regardless of their utility, and so it did.

And then came the pièce de résistance — in order to make these models more complete and satisfying, the brain invented, conceptualized, made up from nothing, the concept of a separate self, something to put in the ‘centre’ of the model which hopefully would make it more useful.

As I think most will admit, once the brain has decided something is true and real, it is very difficult to shift it. It has ‘made up its mind’. So, I would conjecture, ever since then, the brain has rationalized that everything that happens to that separate self is real, that this separate self actually controls the brain and body that invented it, and that everything else around this now-real separate self must perforce also be real — including space, time and other ‘people’ (abstractions of collections of cells and organs within a skin, including the brain that abstracts them and the ‘self’ that presumably sits at the centre of them).

Every decision that is apparently made by this collection, this complicity of cells and organs, is thereafter rationalized as being a decision ‘made’ by the self from its position in alleged control over the brain. And every conceived action of ‘other’ complicities of cells and organs is rationalized as being an action of that complicity’s controlling ‘self’.

This is of course what most of us ‘selves’ take for granted. But science is demonstrating that it just isn’t so. There is in fact, neuroscientists say, no such thing as a ‘self’, and the actions a particular complicity of cells and organs appears to take are in fact autonomous, merely being rationalized (made sense of) in the brain afterwards, as being the ‘self’s supposed action. And quantum science and astrophysics and philosophy are quickly converging on a consensus that there is no real ‘time’ or ‘space’ within which anything ‘real’ can happen — that these are just mental constructs, persuasive but illusory sense-making by the brain. And even more astonishingly, that there is no need for time or space or a separate ‘observer’ for the mathematics and physics to model with delicious precision what is actually apparently ‘happening’.

When this first occurred to me, I set it aside (like other things that seemed to make some sense but which I couldn’t make sense of). I started to explore ideas for ‘realizing’ the illusory nature of my ‘self’ and the apparent ‘unreality’ of time and space and everything separate. This naturally took me into spiritual studies, and then to self-proclaimed spiritual teachers (Eckhart Tolle, Adyashanti, ‘Direct Path’ non-dualists etc) who suggested pathways and practices that might lead to such realization, to a confirmation that this very strong intuition that there was ‘not two’ — nothing separate — was true.

I found the paths frustrating and fruitless (though this character is, by nature, impatient), and finally stumbled upon Tony Parsons and the other ‘messengers’ of what I (and some of them) have come to call Radical Non-duality, which posits this simple, hopeless, pathless statement:

There is no you. The sense of a separate person with free will and choice inhabiting a body is an illusion, an evolutionary misstep, a psychosomatic misunderstanding that arises in creatures with large brains. The brain and body have no need of a ‘self’ in order for the apparent human they are seemingly a part of to function perfectly well. Since there is no you, there is nothing you can do or learn or become to dispel or see through this illusion. It’s hopeless.

Nothing is real. Nothing is separate. There is no thing. There is only this (or everything, or whatever word you want to use), appearing as things and actions in (apparent) time and space. These appearances are not illusions like the self, and they’re not real, or unreal; they are just appearances. Inexplicably. For no reason or purpose. That’s it.

For the past four years I’ve been probing this, convinced that it’s too simple, too pat, and too outrageous to be correct. I am the definitive Doubting Thomas. But today I believe it more strongly, partly because it stands up intellectually so well to new discoveries and doubts, partly because there have been times when there has been a glimpse during which it was seen as obviously true, and partly because, well, it just seems intuitively correct. Something in me resonates with this statement of what is.

In some cases, it seems, the illusion of the separate self can just, without cause or reason, fall away, and, as in the ‘glimpses’, this truth is seen (but not ‘by’ me, not ‘by’ anyone) to be true. And in some cases the falling away of the self is apparently permanent. Frank McCaughey has now interviewed a number of apparent people who say this has apparently happened (but not ‘to’ anyone) and that there is no longer a sense of separation, self, or ‘reality’ ‘there’. Frank’s another Doubting Thomas like me, just as obsessed with this, and just as stubbornly and unwillingly imprisoned by his ‘self’ as I am.

When I first listened to (and later met) Tony and Jim, and then listened to Tim, Kenneth and others, I was suspicious that it was a con — they mostly know each other and in some cases have come to use many of the same words to describe the mystery that this message refers to. But it’s too consistent to be a con — no one could talk about this falsely for 20 years without making some mistake revealing it to be an invention. None of them is making any money communicating this message. And it’s not an easy gig, especially when some of the ‘messengers’ are struggling to make ends meet, continuing to work at terrible jobs, and in a few cases are not terribly well-read or articulate. Still, no matter how variably worded and described, it’s clearly the same message. I’m convinced that if Einstein were alive today he’d be on board with this, and people would be lamenting that he’d lost his edge, and his mind.

The reason that watching the tardigrades puts me in mind of this is that it brings home just how much of what is apparently happening is beyond our grasp, beyond our knowing, beyond our control, not just for now but always. For some, that might be enough to drive them to religion, or spirituality, or therapy, and leave it at that.

But this ‘I’ can’t leave it at that. There is something here, something obvious, something at once awesome and awful, something forever beyond our human selves’ reach. Something I’m guessing that, outside of selves, is universally and perpetually seen. The self does not stand in the way of the apparent complicities of creatures that appear, amazingly, out of nothing, without limit, without beginning or end or purpose or meaning, outside of time and space. Seeing what is is not an issue for the tardigrades, or the jellyfish, or the bats. There — everywhere — everything can see the wonder of everything that is. It is only the spandrel of the human self, that tragic cosmic accident, that cannot see.