This is the 15th in a series of articles on CoVid-19. I am not a medical expert, but have worked with epidemiologists and have some expertise in research, data analysis and statistics. I am producing these articles in the belief that reasonably researched writing on this topic can’t help but be an improvement over the firehose of misinformation that represents far too much of what is being presented on this topic in social (and some other) media.

It’s been two months since my last article on the pandemic. Since then everything has gotten significantly worse:

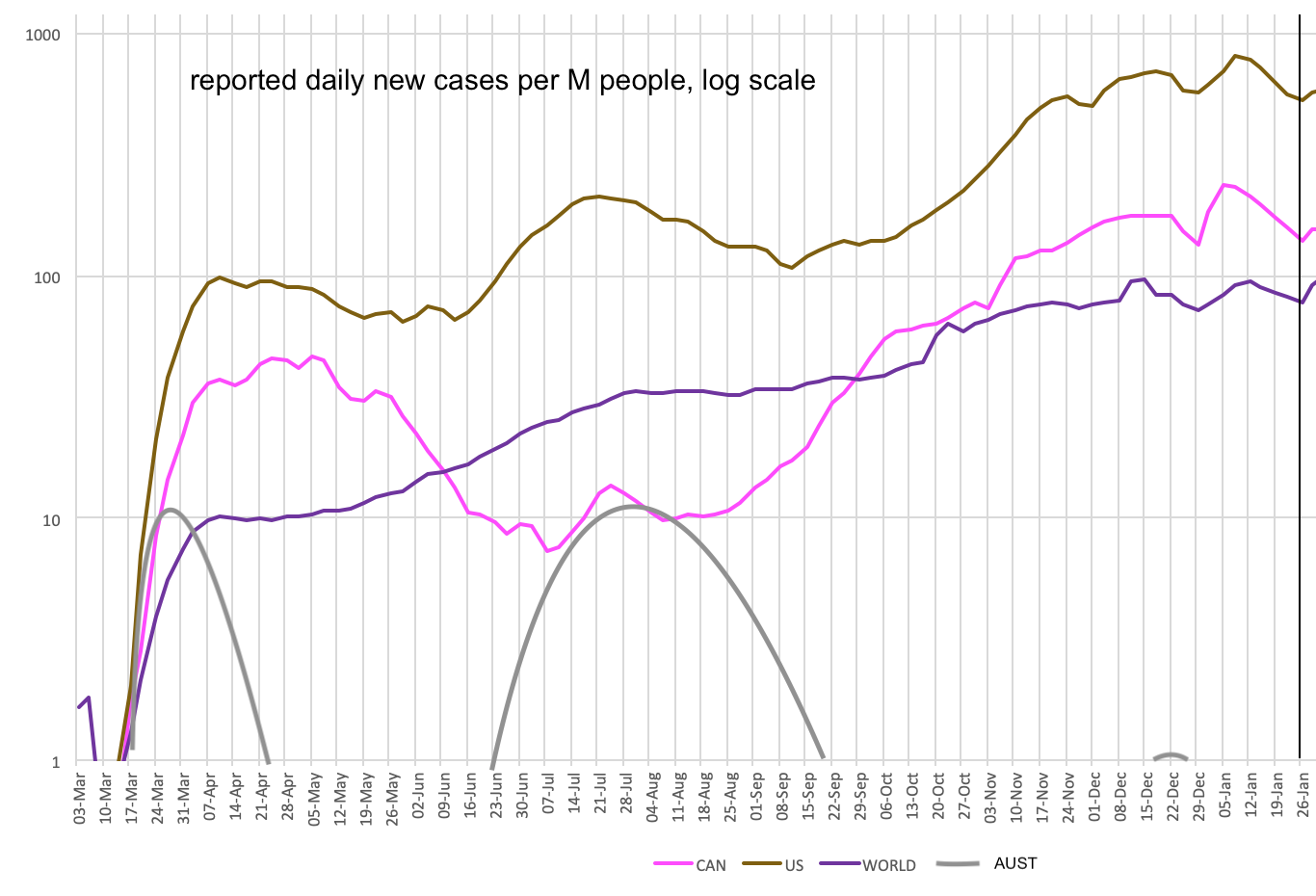

- Infection and death rates have soared in the vast majority of countries, and notably in countries that already had high death tolls. Globally, new cases, daily deaths and hospitalizations are all at record levels. The relentlessly pessimistic IHME was right in their forecasts.

- There are many new variants, and while it is clear they are more infectious (and now the dominant strains in some countries), little is known about them. The higher transmissibility means that many more are likely to fall ill, be hospitalized and die than last projected, perhaps doubling the death count from what it is currently in many jurisdictions.

- We have showed no more competency at rolling out a vaccine to 7.8B people than we showed containing and testing for the disease. “Shambles” would not be an unfair term to use to describe the current state of vaccine distribution and inoculation in all but a handful of countries.

None of this surprises me. In our dealing with climate change, biodiversity die-off, soil depletion, chronic disease management, systemic racism, obscene inequality, the financial and debt bubbles, forest stewardship, and a host of other modern, complex predicaments, our collective response has been, to any objective observer, staggeringly inept.

No one is to blame for that, as much as we’d love to assign it. The reality is that no species is competent at addressing complex predicaments — there are too many moving parts and variables, and no mechanism for coordinated decision-making and action beyond the smallest, local level. That’s why nature, over the past 4.5B years, has evolved life to respond instinctively and locally, not rationally and globally, to crises. And accordingly, life has evolved through many near-extinction events much graver than a human pandemic for that entire 4.5B years, remarkably successfully. It is sheer hubris to suggest that our newcomer human species can ever hope to approach that level of competence. But, it appears from our political and economic evolution, hubris is just about all we have to go on.

For different reasons, Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan, uniquely, have weathered the pandemic largely unscathed and are likely to continue to do so. They have used a radical approach called Go For Zero. It’s extremely effective if applied when the caseload is not already out of control, when it’s applied rigorously and when the government and citizens both follow it. It becomes much harder, but not impossible, when this is not the case. Once again, here are the nine elements of this strategy:

- Make zero cases the explicit goal for the country/state, and implement a specific, public plan to achieve that goal.

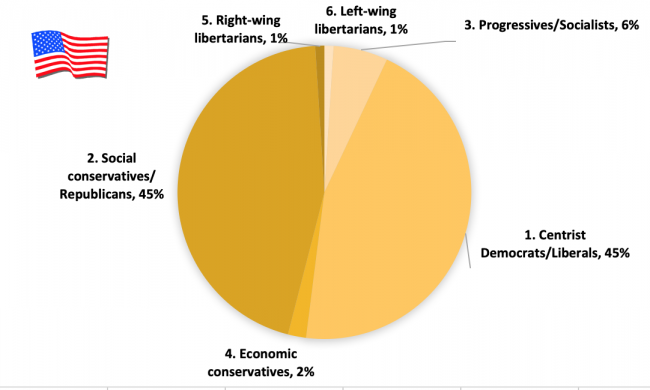

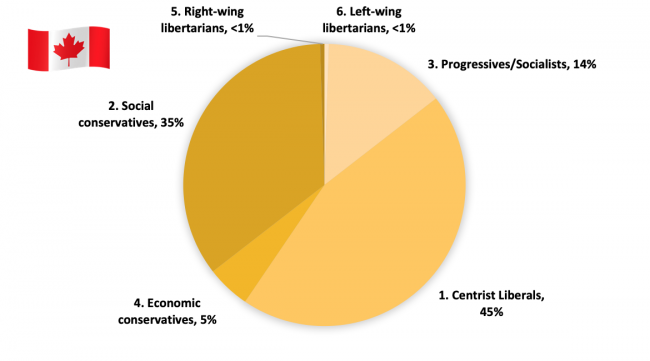

- That plan will likely include a complete lockdown for all ages until the number of reported new cases has been reduced to approximately 3 per day per million people. [Current level in the US is 500/day/M; in Canada it’s 120/day/M, but it was about 10/day/M for much of the summer before the recent surge]. Once the 3/day/M level has been achieved, certain specific low-risk, high-benefit activities can be permitted and encouraged. Additional easing can be permitted once new cases drop to 1/day/M people, and considerable further easing once zero new cases have been reported for a week.

- Everyone entering the country must be tested at the border and/or strictly quarantined for 14 days or until a negative test is confirmed.

- Stringent, properly staffed contact tracing and isolation must be in place for any cases that do arise. Non-cooperation and lying about exposure should be prosecutable. Lives depend on it.

- Testing must be easily and universally accessible for free, and test results must be able to be produced and communicated within 24 hours. The technology to do this exists; the capacity in most jurisdictions currently does not.

- Testing with digital attendance record-keeping and follow-up must be instituted in all public venues (restaurants, arenas etc). [Australia’s success means that up to 35,000 people can now attend stadium events with zero resulting cases.]

- Masks are mandatory in all public places in areas which have had recently-reported cases. In all other places they are optional.

- Economic supports for all those disadvantaged by restrictions must be available.

- Strict enforcement of quarantine must be maintained; no exceptions.

The eventual availability of widely-instituted vaccination has absolutely no effect on this strategy — its impact is at least 3-6 months away. The new variations mean that the importance of doing this now is even greater.

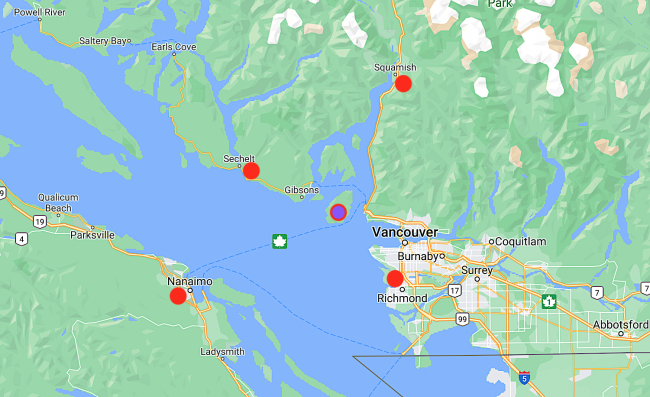

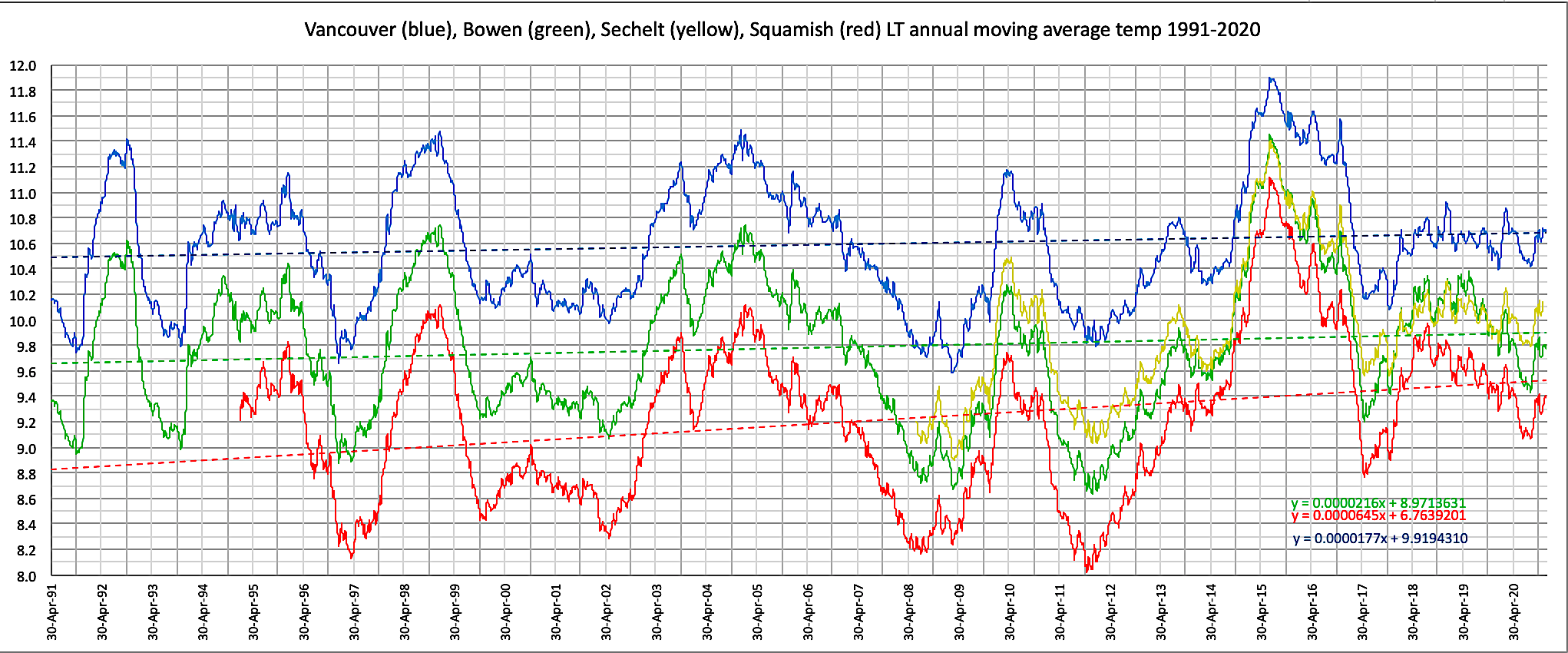

The charts above show the situation last summer in Canada: throughout June, July, and August, daily new cases were about 10/M people (about 400 new cases nationwide per day); nationwide new deaths were about 6 per day). Had the government implemented the Go For Zero strategy then, the lockdown would have lasted a few weeks and we would now be in the same situation as Australia — almost zero new cases, easy to monitor and sustain, and open arenas, restaurants and public places. (In fact, in July, Canada’s new cases/day/M was briefly lower than Australia’s.)

But we didn’t do that. We couldn’t. Regulatory authority is weak (a special emergency declaration is required to overcome Canadians’ constitutional freedom to leave and to return to Canada at their leisure), and authority is split among all the provinces, which have different political stances and bureaucracies. Advice from higher authorities (WHO, national and nearby country CDCs) was muddled, cautious, and too often simply wrong (poor and inadequate data collection, deregulated agencies, underfunded research, inexperience, unwillingness to confront incompetent and weak political leaders). And unlike Australia, we were simply incapable of learning and radically changing direction on the fly as was needed. And now we’re facing the same thing with the vaccine — overpromises, pathetically underdelivered.

In a new article, Andrew Nikiforuk describes the countless other bumbling errors that have been made so far, and says that, while it will be much harder now, with case levels in Canada 12 times higher than last summer, it is even more imperative. He also shows that Canada has been far from unique in its incompetence. Just as one example, all the evidence suggests that children with CoVid-19, many of whom are asymptomatic, are just as infectious as adults, and that homes are primary sources of disease spread; so why are we even having a debate about opening schools?

We’re at a crossroads. North American governments, looking at a brief drop in cases before the new variants drive the numbers up yet further, are inclined to continue their hapless “wait and see” approach. That decision will likely cost 200,000 more American lives and 15,000 more Canadian lives, unnecessarily. And that’s if we avoid dangerous mutations, hyper-transmissible new strains, and further delays in vaccinations.

So the dilemma now is that there’s a tendency to continue with current weak restrictions, as by the time the vaccine has finally been given to enough people to achieve herd immunity, we’ll already have lost about half the lives we might have lost had we done nothing at all. We can just shrug and say “we did our best” and set up the necessary triage spaces and freezers in parking lots around our hospitals and health care and old age institutions. It’s easy to say “we didn’t know” or blame the vaccine distributors or reckless citizens or other scapegoats. The 15,000 unnecessary additional Canadian deaths and 200,000 unnecessary additional American deaths are just collateral damage of our valiant “best efforts”.

The problem is that if there is a new, much more transmissible, or more virulent mutation, we’re only seeing the start of the carnage this evolving pandemic has created. We might get lucky. Or we might be back to square one, with a new pandemic virus that the vaccine (which was developed a year ago, before a pandemic was even declared — thats how cumbersome our approval and response systems are) doesn’t work on, or if a new variant, like the 1918 mutation, mainly affects young people, or if it is sufficiently different that those infected with the original variant have no immunity to it. That would mean death tolls at least an order of magnitude higher than what we’ve seen to date.

Such a pandemic is inevitable. If not a variant of the current virus, it will emerge sooner or later. And we show no indications that we’ll be any more prepared then than we are now.

We could eliminate the cause — banning factory farming and all the other ghastly CAFE operations, prohibiting the killing and sale of “exotic” animals for meat and medicines, and prohibiting the exploitation of the last remaining areas of wilderness whose endemic diseases we don’t know and have no resistance to. But we won’t. We can’t.

We could prepare now for a global Go For Zero strategy so when the next pandemic hits we’ll be ready like Australia, New Zealand, and Taiwan. But we won’t. We can’t.

This is not an issue of collective will, organization or collaboration. Just like we’ve caused climate change, we created this recent surge of global pandemics with good intentions, and ended up opening a pandora’s box we cannot close. That is the nature of predicaments in complex systems, and the nature of our (and probably all other) species: Predicaments cannot be rationally ‘solved’ because it is impossible to know what all their causes are, or what the impact of any interventions to try to remedy them will be. And we are incapable of acting globally: We’ll never get all 7.8B of us, or even all of our political representatives, to agree on a single narrative, strategy or plan of action. That’s not how human politics has ever worked.

That is why I say we are incompetent when it comes to dealing with the complex existential threats we face today, of which pandemics are just one, and not even the most serious. Incompetent does not mean stupid, evil, or ignorant, or some combination of these. Incompetent means we, humans, are just not up to the task. Over billions of years nature has endowed creatures with instincts, because, at the local level, they work. Nature has evolved life to adapt to changing conditions, because such changes are inevitable. Rationality and collective problem-solving, for all the inventions and technologies they have spawned, have only, in the end, created even greater problems, and predicaments that cannot be solved at all.

So it would be nice if we were to, in Canada, or globally, sooner or later, adopt a Go For Zero strategy. It could save millions of lives, and actually hurt the economy less and help the environment more.

And it would be nice if, globally, we were ban factory farming, exotic animal hunting, and the clear-cutting of our last wilderness. It would end a vast and staggering barbaric cruelty, make our diets much healthier, dramatically reduce chronic as well as infectious diseases, and help the environment.

But we won’t. We can’t. We’ve got the right idea though. If only that were enough.