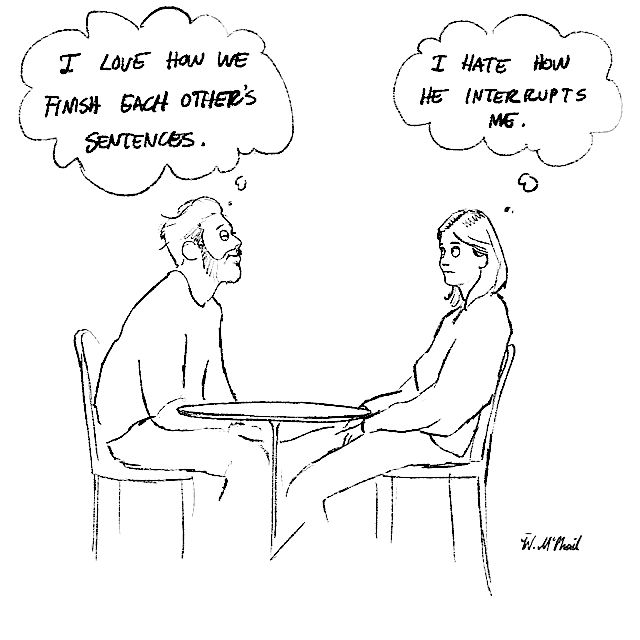

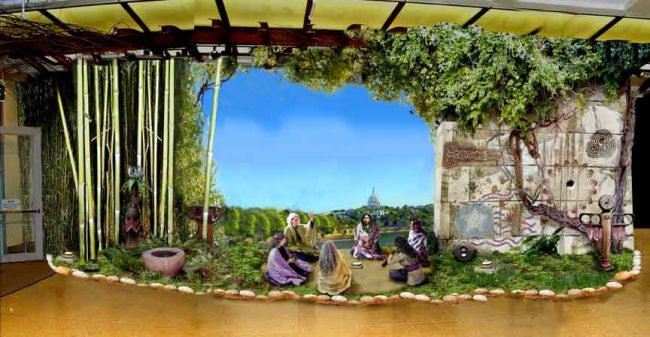

council of clan mothers in post-civ culture; diorama from Afterculture

It’s not often that a book comes along that so undermines my beliefs that it brings about a seismic shift in my worldview. Sixteen years ago John Gray’s Straw Dogs did exactly that — convincing me that our civilization could not be saved, and, eventually, that it did not need or warrant saving. Now a new book has come along that is persuading me that, while we cannot do anything to prevent civilization’s collapse, we can do a lot more positive and creative things than we think (or that I thought) we could do, and we don’t have to wait for collapse.

The hyperbolic title of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything was apparently deliberately chosen to get in the face of anthropologists and archaeologists who have, for too long, been far too sure of themselves (at least in public) about the evolution and nature of our species and its place in the world. Its provocative and controversial thesis is:

The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make, and could just as easily make differently.

(I could picture John Gray’s brow furrowing when he read this.) The world may be staggeringly complex, the authors assert, and we cannot come even close to knowing it well enough to predict the consequences of our impacts on it, but that doesn’t mean we are doomed to continue our current nihilistic path to global homogeneity, obscene inequality, suffering, and destructiveness. The history of humans and civilizations does not follow an inevitable linear trajectory from tribal egalitarianism to hierarchical agricultural and industrial settlement to unsustainable and unmanageable complexity and hence ghastly collapse, they insist. The story of humans is much subtler and more varied than that.

Ultimately I want to explain how this book’s coherent, playful, and exhaustively researched and documented arguments have changed how I see our world and our place in it (including my own), but first let me step back and walk you through the six main points I think this 600+ page book tries to make:

1. How we got stuck where we are

The core idea of the book is that what has led to our civilization’s dysfunction (and our unhappiness with it) is not so much the inequality, destruction and hopelessness of our situation, as the (personal and collective) loss of three ‘basic freedoms’ —

- the freedom to move elsewhere if you’re unhappy;

- the freedom to disobey if you disagree with what you’re told; and

- the freedom to imagine, create and explore other and different ways of living and being

The authors argue that the loss of the first freedom can lead to the loss of the second and thence to the loss of the third. But they say what lies behind the loss of these freedoms is not so much things like laws, overdevelopment of land and resources, and property rights, as a severe imaginative poverty, one that has been conditioned in us by an increasingly homogeneous and demoralizing culture. This conditioned behaviour, they say, might be overcome:

If something did go terribly wrong in human history – and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did – then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence, to such a degree that some now feel this particular type of freedom hardly even existed, or was barely exercised, for the greater part of human history. How did it happen? How did we get stuck? And just how stuck are we really?

The authors assert that we can’t know the answers to these questions, but they do speculate on them, and suggest these are the most important questions we can usefully be asking today.

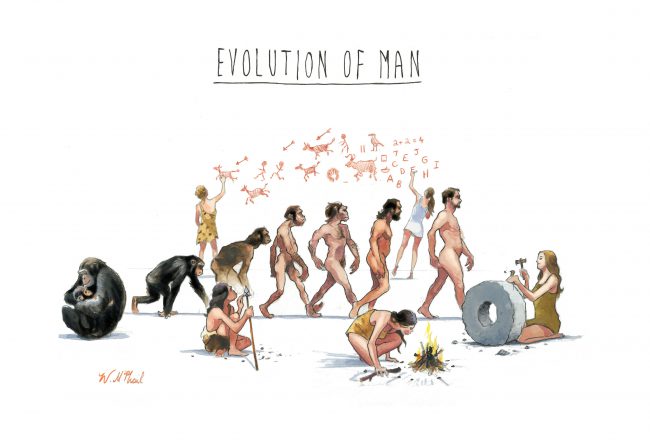

2. There are, and have always been, many, and very different, ways to live in human society

Our narrow, linear, and incorrect view of how societies have historically developed causes us to underestimate the variety of forms of social organization that are still possible today.

The authors (wisely, I think) don’t talk about climate change, since I suspect they think it’s inexorable, but instead focus on their areas of knowledge and expertise — anthropology and archaeology. Their message is that our culture, and hence our future, is not limited by the constraints of our civilization, and that ‘ancient’ history is replete with examples of rapid, and sometimes whimsical, cultural change that created and transformed societies:

Perhaps if our species does endure, and we one day look backwards from this as yet unknowable future, aspects of the remote past that now seem like anomalies – say, bureaucracies that work on a community scale; cities governed by neighbourhood councils; systems of government where women hold a preponderance of formal positions; or forms of land management based on care-taking rather than ownership and extraction – will seem like the really significant breakthroughs, and great stone pyramids or statues more like historical curiosities.

What if we were to take that approach now and look at, say, Minoan Crete or Hopewell not as random bumps on a road that leads inexorably to states and empires, but as alternative possibilities: roads not taken?… People did actually live in those ways, often for many centuries, even millennia. In some ways, such a perspective might seem even more tragic than our standard narrative of civilization as the inevitable fall from grace. It means we could have been living under radically different conceptions of what human society is actually about. It means that mass enslavement, genocide, prison camps, even patriarchy or regimes of wage labour never had to happen. But on the other hand it also suggests that, even now, the possibilities for human intervention are far greater than we’re inclined to think.

3. Human advancement comes not from individual genius but from collaboration, imagination, experimentation, and play, over long periods of time.

The authors insist that innovation, imagination and discovery is not the territory of genius or new technology but of collective imagination, communication and incremental and serendipitous experimentation (much as how nature works):

Who was the first person to figure out that you could make bread rise by the addition of those microorganisms we call yeasts? We have no idea, but we can be almost certain she was a woman and would most likely not be considered ‘white’ if she tried to immigrate to a European country today; and we definitely know her achievement continues to enrich the lives of billions of people. What we also know is that such discoveries were, again, based on centuries of accumulated knowledge and experimentation… – the basic principles of agriculture were known long before anyone applied them systematically – and that the results of such experiments were often preserved and transmitted through ritual, games and forms of play (or even more, perhaps, at the point where ritual, games and play shade into each other)…

One of the most striking patterns we discovered while researching this book – indeed, one of the patterns that felt most like a genuine breakthrough to us – was how, time and again in human history, that zone of ritual play has also acted as a site of social experimentation – even, in some ways, as an encyclopaedia of social possibilities.

4. We are not inherently a violent and destructive species

The authors assert, again based on exhaustive evidence, that humans are not intrinsically what John Gray calls “homo rapiens” — destined by nature to kill, destroy and ruin — and that neither war nor slavery has ever been a necessary part of most human societies, even while they acknowledge these atrocities have been a part of many past societies.

Their argument for the myriad of possible reasons underlying the existence of war and slavery in pre-history and history is very complex, and they admit they’re largely conjecture and need further exploration:

War did not become a constant of human life after the adoption of farming; indeed, long periods of time exist in which it appears to have been successfully abolished. Yet it had a stubborn tendency to reappear, if only many generations later. At this point another new question comes into focus. Was there a relationship between external warfare and the internal loss of freedoms that opened the way, first to systems of ranking and then later on to large-scale systems of domination?…

Sovereignty, bureaucracy and politics are magnifications of elementary types of domination, grounded respectively in the use of violence, knowledge and charisma… Some ‘early states’… deployed spectacular violence at the pinnacle of the system (whether that violence was conceived as a direct extension of royal sovereignty or carried out at the behest of divinities); and all to some degree modelled their centres of power – the court or palace – on the organization of patriarchal households. Is this merely a coincidence?

5. Power has been manifested and exercised throughout human existence in many different, and often peaceful, ways

The authors explore in depth the connection between violence, freedom, slavery, ‘inequality’, and power. Power, they assert, in prehistoric times never flowed from wealth — not because there was no inequality of wealth but because wealth in those societies was valued only as its value as a gift (gifting being a most honourable human activity), and because wealth couldn’t be used to ‘buy’ power, or indeed anything else:

Existing debates [about freedom] almost invariably begin with terms derived from Roman Law, and for a number of reasons this is problematic. The Roman Law conception of natural freedom is essentially based on the power of the individual (by implication, a male head of household) to dispose of his property as he sees fit. In Roman Law property isn’t even exactly a right; it’s simply power – the blunt reality that someone in possession of a thing can do anything he wants with it, except that which is limited ‘by force or law’.

This formulation has some peculiarities that jurists have struggled with ever since, as it implies freedom is essentially a state of primordial exception to the legal order. It also implies that property is not a set of understandings between people over who gets to use or look after things, but rather a relation between a person and an object characterized by absolute power… Roman Law conceptions of property (and hence of freedom) essentially trace back to slave law,… [which endowed] the power of the master and which rendered the slave a thing.

6. Many past societies have scaled quite dramatically through networks and confederacies of collaboration and exchange, without resort to hierarchy, coercion, oppression, or violence

The authors go on to argue that it is completely untrue that “structures of domination are the inevitable result of populations scaling up by orders of magnitude”, citing many historical examples to the contrary, and add:

[It is equally untrue that] the larger and more densely populated the social group, the more ‘complex’ the system needed to keep it organized. Complexity, in turn, is still often used as a synonym for hierarchy. Hierarchy, in turn, is used as a euphemism for chains of command.

Large human settlements, they say, have historically more often been networks of collaboration and exchange than complex, hierarchical structures. They cite anthropologist Carole Crumley:

Complex systems don’t have to be organized top-down, either in the natural or in the social world. That we tend to assume otherwise probably tells us more about ourselves than the people or phenomena that we’re studying.

Many early cities operated, they say, “as civic experiments on a grand scale, which frequently lacked the expected features of administrative hierarchy and authoritarian rule.” Early civilizations were often coalitions or confederacies over large areas, and the emergence of more concentrated confederacies may have had more to do with limitations on space for expansion than anything else. Warfare, hierarchy, patriarchy and domination were not inevitable consequences of such confederacies, though of course they did arise in some of them, and the biggest unanswered question is, why?

On the final page of the book, they repeat a quote that is one of my favourites:

Max Planck once remarked that new scientific truths don’t replace old ones by convincing established scientists that they were wrong; they do so because proponents of the older theory eventually die, and generations that follow find the new truths and theories to be familiar, obvious even. We are optimists. We like to think it will not take that long.

None of this, of course, changes our current horrific predicament and (most likely) the inevitability of this civilization’s collapse. But it does open some interesting possibilities for new and unimaginably different types of societies both during and after collapse. If only we can shake the yoke of imaginative poverty, and our ‘stuckness’ in the current way of thinking — that our civilization culture is (at least now) the only way to live.

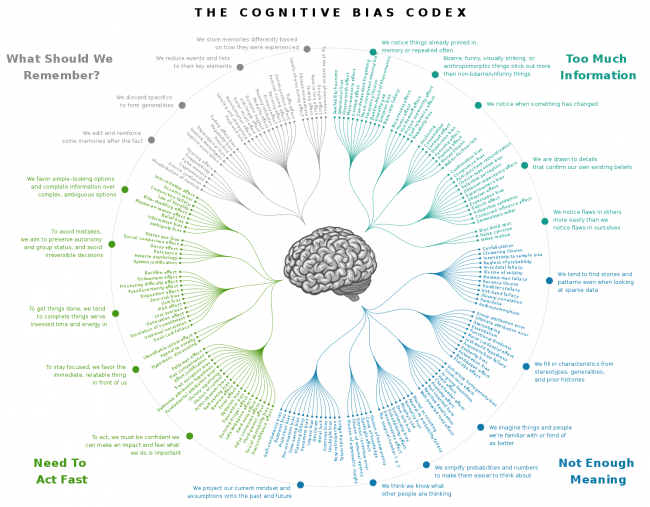

Why, I kept thinking as I read the book, are we “stuck” in this way of thinking that ours is the only way to live? Are we, like my fictional dog Lucky, condemned to keep returning to places and systems that abuse us, that waste our lives and energies, and that we know just don’t work, because we can’t imagine anything ever being, or ever having been, otherwise? Is this the only way to live, or just the only way we know?

Serendipitously, I have recently been reading about double binds, a psychological concept first introduced by Gregory Bateson, to explain how parents often (mostly unintentionally) invoke trauma in their children by framing their demands and expectations in “can’t win” terms — no matter what the child does, or doesn’t do, they feel they have failed, and let themselves and others down.

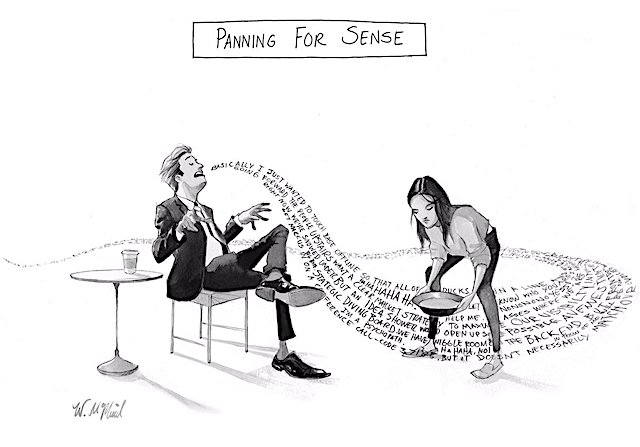

It occurred to me that many of those in power who want to suppress dissent and compel obedience to their authority, use similar means to paralyze citizens and “consumers”. Shut up and support and vote for right-wing Biden, or you’ll get fascist Trump. Buy our crap product, or be seen as ugly, stupid, or otherwise inferior in the eyes of those you care about. And if you don’t, your old product will break or be “deprecated” next year anyway. Shut up and take this Bullshit Job (or essential job) with its annual pay cut, absurd working conditions, and zero benefits, or we’ll shame you, starve you, or throw you in jail. In terms of the book’s three freedoms, this is simply: Stay, obey, and accept that this is the only way to live.

There is perhaps a similar double bind with climate change: We are persuaded it’s “up to us” and that we should not criticize mega-polluters or regulators because “we’re all part of the problem”. Or else we see that what we do as individuals is utterly inadequate, but are told that “the system” can’t change to address ecological collapse because it has too much inertia or too much momentum or too many interrelated moving parts. Or that tending to ecological collapse would inevitably bring horrific economic collapse, and we wouldn’t want to be blamed for that, would we? Pick your poison. So we just feel hopeless and give up, or turn to denial, or to faith in technology, or the rapture, or some other salvationist escape from reality. So we are paralyzed — whatever we do, or don’t do, is wrong, insufficient, defeatist, selfish, irresponsible.

The authors of The Dawn of Everything are trying to tell us we’ve been had when we feel this way. That it doesn’t have to be this way. Perhaps the current Great Resignation is a small glimmer of realization of this, of what Daniel Quinn called “walking away” from a dysfunctional and collapsing society that is no longer serving us, and which actually isn’t the only way to live.

It seems strange for me to be writing these words — me, the self-proclaimed “joyful pessimist” who has insisted that nothing we can do will make a difference, so we should (gently) just enjoy our lives for what they offer, and appreciate that we’re doing our best, and that hard times lie ahead.

Derrick Jensen talks about moving “beyond hope“, and that is perhaps the shift that reading The Dawn of Everything has stirred in me. Derrick says that, even though “we’re fucked”, we should still work to clean up the river near us, to carefully dismantle that dam that does so much more harm than good, or do work at a food bank or animal rescue centre or homeless centre.

But maybe, if we start to work and think together about what “walking away” really means, with genuine dialogue, imagination, and helping each other disentangle and deactivate the double binds, we might find that, though I don’t share the Davids’ belief that it will be easy, we might discover that we can “make the world differently”, or at least small and important parts of it.

If we’re discouraged, we might look at an ecological principle called trophic cascades. The principle applies specifically to food pyramids in the natural world and how small interventions in them can have dramatic, far-reaching and permanent impacts on entire ecosystems. A classic example is how the reintroduction of wolves into an altered ecosystem completely remade and rebalanced an entire forest ecology, even affecting the shape and channels of rivers and the forest’s microclimate.

But the word trophic actually has a much broader definition — it means to make thrive — and that’s the sense I’m thinking about now.

So rather than trying to control and re-form societies by pioneering new and healthier ones, what if we instead realized that we are just part of a more-than-human ecology, and that, rather than imposing some new human model on “the environment”, we could by small, gentle interventions (a thousand carefully-considered small sanities) unleash a trophic cascade, and “make thrive” an entire ecosystem of which we are a part.

It seems to me this is what the authors might have been getting at when they suggested we could “make the world differently”. We, humans, don’t make the world. We, all of the creatures living and being in it, make the world what and how it is. The play, the experiments, the imagining, and the collaboration that we all, human and more-than-human, take part in — noticing, trying, exploring, tweaking, studying, learning, conversing, imagining, playing — this is how we, together, make the world. It is not a design exercise — Haven’t we learned that? It is far too complex for that, too unpredictable, too unknowable.

So how would we go about it? How would we go about making everything differently, if we walked away from this civilization? (And yes, we can!)

I have no idea. We would have to decide this collectively, figure it out together. Listen to what the birds tell us, and pay attention to what the rest of the world’s creatures show us. Make some shit up and see what happens. Make it safe to fail. Make it fun. Dialogue about what’s possible. Dream. Forget about the idea of impossible. Start fresh. Challenge everything, playfully. Start over. Improvise. Break all the rules. Share everything, especially knowledge and power. And, in the spirit of the book, cherish the three freedoms, regained.

Perhaps the “dawn of everything” in the book’s cryptic title doesn’t refer to a new understanding of the dawn of how human societies evolved in the past. Perhaps instead it’s the authors’ whispered suggestion that this could be the time of the dawn of infinite possibilities, the dawn of everything that is yet to come in the human experiment, all the astonishing things we have not yet tried, or have tried and forgotten.

This joyful pessimist wants to know. Wanna start a trophic cascade with me?